Category: News

La Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry — Part Four: Muller and Hector Guimard, other achievements.

This series of articles devoted to the company of the ceramist Émile Muller in Ivry gives an overview of his creations in the field of Art Nouveau. In this fourth article, we try to identify the collaboration between Muller & Cie and Hector Guimard.

The Villa Charles Jassedé

Shortly after the construction of Louis Jassedé’s private mansion began in 1893, rue Chardon Lagache in Paris, Guimard began the construction of a villa in the Paris suburbs for Charles Jassedé, Louis’ cousin, at 63 route de Clamart (currently avenue du Général-de-Gaulle) in Issy-les-Moulineaux. As usual, he pushed the building back to the edge of the plot so that he could make the most of the garden.

Villa Charles Jassedé, 63 avenue du Général-de-Gaulle at Issy-les-Moulineaux. Photo Wikicommons, crédit : Patrbe/CC BY-SA.

Built on a much smaller budget than the Jassedé Hotel, this country house nevertheless presents some picturesque details such as its two deflections on the street façade, the high chimneys and the corbelling (more symbolic than real) of the straight span of this facade by oblique irons.

Villa Charles Jassedé, 63 avenue du Général-de-Gaulle at Issy-les-Moulineaux. Photo internet, Laurent D. Ruamps.

On this occasion, Guimard does not create new models of architectural ceramics, but simply draws from those he already has published at Muller & Cie and even from those in the catalogue. He therefore reuses his metope no. 13 to girdle the base of the corbelled bay (five metopes on the street side, seven on the right-hand side of the façade), also taking up the framing by angle irons and iron blades as for the lintels of the windows of the Hotel Jassedé.

La Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry — Part Three: Muller and Hector Guimard, Hotel Roszé and Hotel Jassedé.

This series of articles devoted to the company of the ceramist Émile Muller in Ivry gives an overview of his creations in the field of Art Nouveau. In this third article, and then in the next one, we address the collaboration between Muller & Cie and Hector Guimard.

Our articles will not present all of Guimard’s architectural ceramic designs known and intended for Muller nor all of the instances of use of his decorative panels by other architects. This exhaustive study is being carried out in parallel for the constitution of a specific repertory.

Hector Guimard is a special case among the modern architects who supplied models to Muller & Cie, since he called upon the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry for the decoration of his first villas built in the West of Paris in the early 1890s. These orders immediately led to the publication of models. But curiously, as soon as the Castel Béranger was built in 1895-1898, Guimard no longer seemed to place orders with Muller & Cie and turned to Gilardoni & Brault and Alexandre Bigot. Almost a decade later, however, 14 of his models still appear in Muller & Cie’s 1904 catalogue n° 2.

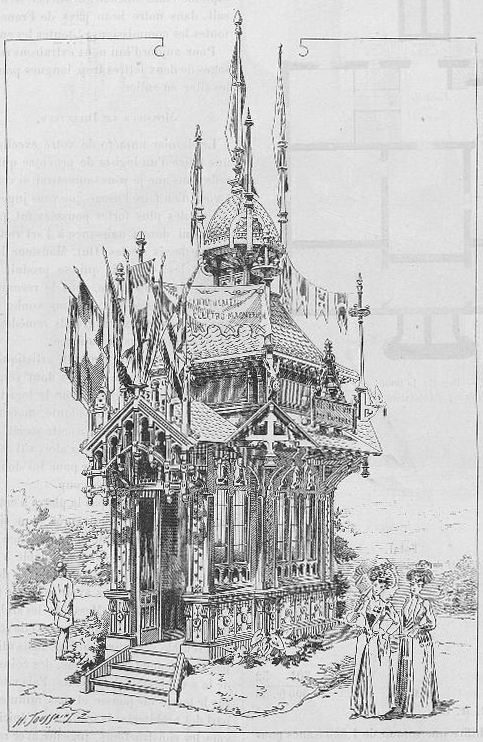

From his first known construction, a modest pavilion praising the therapeutic methods of electricity and electromagnetism[1] for an obscure Ferdinand de Boyères at the 1889 Universal Exhibition, Guimard used ceramics[2] to decorate the panels inserted in the joinery. The professional magazine La Construction Moderne of 22 March 1890 gives an engraving of it (probably from a photo) but we do not know which ceramic models were used or who was the supplier.

Guimard’s “Pavillon for the application of electricity to medicine” at the 1889 Universal Exhibition. Illustration by Henri Toussaint published in La Construction Moderne of 22 March 1890. The ceramic decorations are on the basement as well as on the panels separating the windows. Gallica BNF website.

Hotel Roszé

Two years later, in 1891, for the Hotel Roszé at 34 rue Boileau in the 16th arrondissement, we have the certainty of a real collaboration between Guimard and Muller & Cie thanks to the presence of several panels of the Hotel on the 1904 catalogue n° 2. At that time, Guimard was only 24 years old and he was far from having the notoriety that would be his from the Castel Béranger. The novelty of his models, which seems less obvious today, must have been enough for Louis d’Émile Muller to feel that this young architect deserved attention.

The Hotel Roszé, 34 rue Boileau in Paris, photograph taken in 1975. At that time the ceramic panels on the front and back facades were masked by a coat of paint. ©Bildarchiv Foto Marburg.

The friezes on either side of the lintel[3] of the first-floor window on the left-hand span of the street facade are clad with four-part panels showing a branch from which a blue and a white flower emerge alternately.

La Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry — Part Two: Muller and Art Nouveau

This series of articles dedicated to the company of the ceramist Émile Muller in Ivry gives an overview of his creations in the field of Art Nouveau. The first article summarized the history of the company. In this second article we look more precisely at the collaborations with the artists and architects of this artistic movement. The third and fourth article will focus on Hector Guimard’s model editions at Muller & Cie and the fith on the fireplace sector.

Following the death of Émile Muller in 1889 after the Universal Exhibition, his son Louis d’Émile Muller took over the management of the company. The latter developed an artistic sector by publishing contemporary artists and intensifying relations with architects for the creation of new models to be published or not.

The private mansion known as La Pagode, built in a Japanese style in 1895-1896 by the architect Alexandre Marcel for the director of Bon Marché, at 57 rue de Babylone in Paris, is a good example of this. Only a part of the enamelled stoneware decoration can be found in the catalogue.

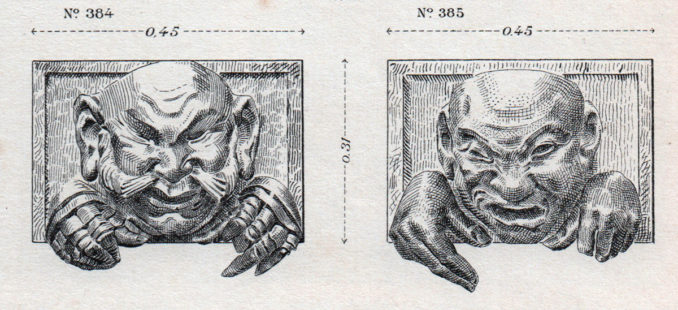

Two panels from the decoration of La Pagode, architect Alexandre Marcel, 1895-1896, 57 rue de Babylone, Paris. Catalogue Muller et Cie No. 2, 1904, pl. 15. Private collection. Each panel: 12 kg; red or white terracotta: 15 F-gold; enamelled terracotta: 30 F-gold; unenamelled stoneware: 20 F-gold; enamelled stoneware: 40 F-gold.

Among the young designers who came into contact with Muller & Cie many will participate in one way or another in the Art Nouveau artistic movement, focused on decorative art and architecture. Their work will generate a large number of new models that are likely to be reused by others. It is therefore essential for a company such as the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry to keep up to date and to be able to supply without delay those architects, contractors and decorators who are not themselves creators but who wish to give their work a modern look. The Muller & Cie catalogues will therefore include a significant number of Art Nouveau style models.

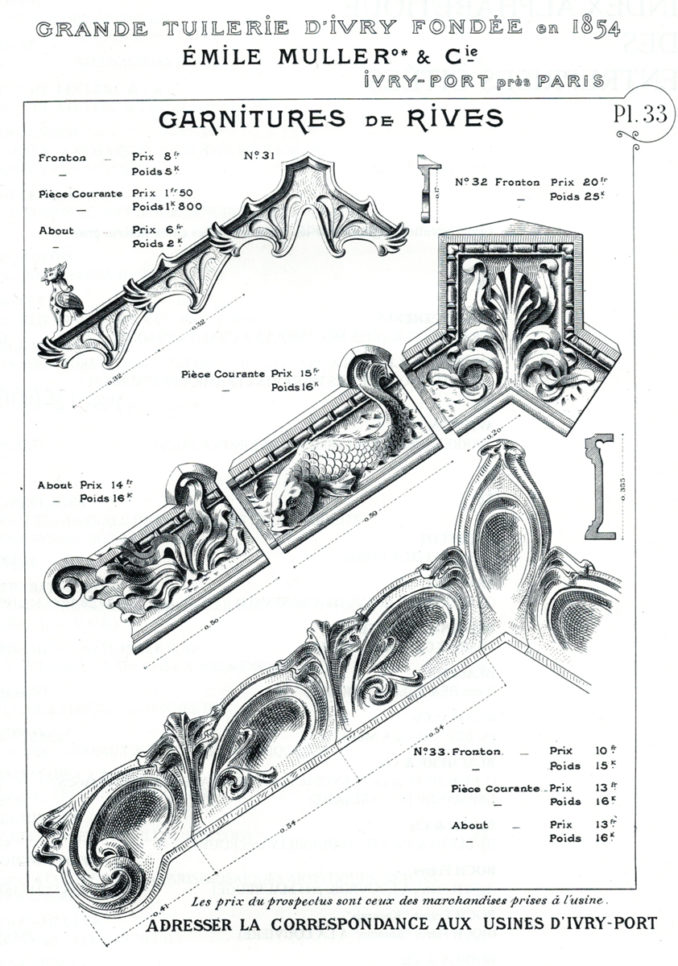

Catalogue n° 1, which includes building materials with bricks and tiles, is enriched with models in which Art Nouveau makes a discreet appearance on plate 33 with two models of verge tiles and pediments which frame a more traditional neo-Renaissance model. These are models not signed by an architect and were therefore purchased from an anonymous industrial artist.

Verge tiles from the Muller & Cie catalogue n° 1, pl. 33. 1903. Reproduced from La Céramique architecturale à travers les catalogues des fabricants, p. 167.

We will rely more readily on the plethoric catalogue no. 2 of 1904, which is mainly devoted to products for exterior and interior architectural decoration, but which also includes vases, pieces of art and trinkets. Many well-known artists can be found in this catalogue, and among those who worked in the Art Nouveau movement are the sculptors Pierre Roche, Ringel d’Illzach, Jean Dampt, Timoléon Guérin and Louis Chalon.

The Grande Tuilerie at Ivry — Part One: the Muller company

This series of articles dedicated to the company of the ceramist Émile Muller in Ivry gives an overview of his work in the field of Art Nouveau. In this first article, we address the history of the company and the variety of his works. A second article will focus on Muller’s production in the Art Nouveau style, the third and fourth articles on Hector Guimard’s model editions and a fith on the fireplace sector.

Émile Muller (1823-1889) was born in Altkirch in Alsace, near Mulhouse. Coming from a well-to-do family, he completed his studies in Paris, graduating from the Ecole Centrale des Arts et Manufacture in 1844. He was then a professor of civil engineering for 24 years, starting in 1864.

-

Portrait of Émile Muller. Documentation center of the École Centrale Paris.

His involvement in the field of education is also shown by his participation in the foundation of the Special School of Architecture[1] and the (Paris) Free School of Political Science (now Sciences-Po). He also presides over the Society of Civil Engineers, where he will have Gustave Eiffel as his successor. Motivated by social ideas, after having built several public facilities, Émile Muller built a workers’ housing estate in Mulhouse in 1853, the first French experiment in decent family housing with gardens. He was also committed to protecting workers from industrial accidents.

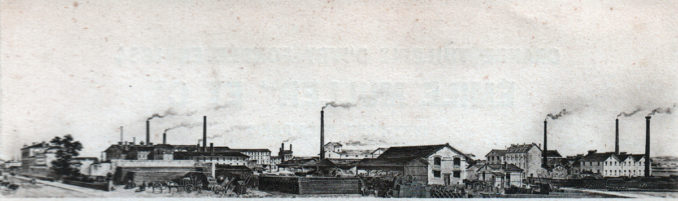

The following year, in 1854, Émile Muller founded a tile manufacturing company in Mulhouse, then a few months later bought a large piece of land to found the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry (the large Ivry tile plant), located on the banks of the Seine, on the Paris-Basel main road, near clay quarries in the southern suburbs of Paris. A showroom and sales room will be opened at a date that we do not know, but probably much later, at a more prestigious address: 3 rue Halévy, near the Paris Opera House.

General view of the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry. The front of the factory along the road facing the Seine river is on the left hand side. Catalogue Muller & Cie n° 2, 1904, p. 1. Private collection.

At the beginning the factory produces interlocking tiles using the process patented by the Gilardoni brothers, also from Altkirch.

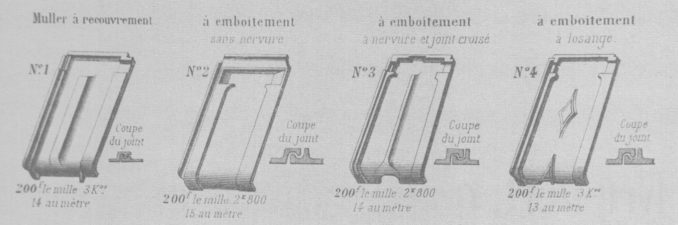

Interlocking tiles. Catalogue Muller & Cie n° 1, 1895-1896. Coll. Library of Decorative Arts.

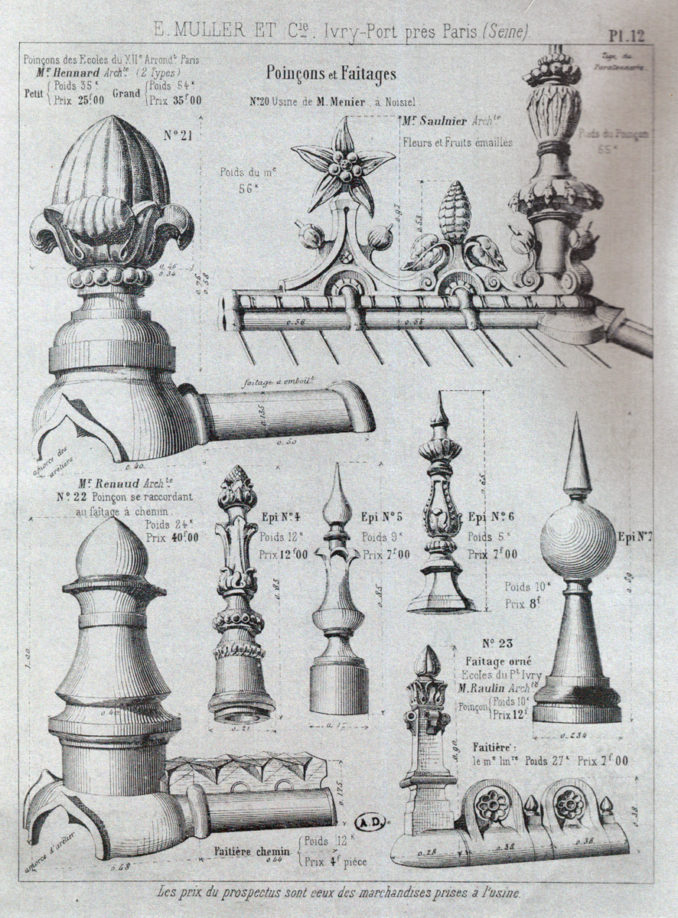

Roofing accessories are an important part of the production because they make it possible to customize a building. A number of special models are therefore created by several architects, which can then be edited.

-

Ridge models. Muller Catalogue Muller & Cie n° 1, 1895-1896, pl. 12. Coll. Library of Decorative Arts.

After starting the manufacture of enamelled products in 1866, the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry diversified its activities by producing raw and enamelled bricks and terracotta facade decorations, both raw and enamelled. Their composition allows them to be fired at high temperatures, making them waterproof.

Enamelled bricks Muller on an building entrance, Croix Faubin street, 10, in Paris. Photo by the author.

In 1871-1872, Muller provided his first large-scale architectural decoration for the Menier chocolate factory’s mill in Noisiel, the world’s first building with a load-bearing metal structure, designed by the architect Jules Saulnier.

Mill of the Menier chocolate factory at Noisiel Jules Saulnier architect, 1871. Photo internet.

Soon after, in 1875, the factory had 150 workers. Muller is of course present at the Universal Exhibitions, the one of 1867 and the one of 1878 where he ensures the success of architectural ceramics. At the 1889 Universal Exhibition, the domes of the Palais des Beaux-Arts and the Palais des Arts libéraux adorned with his turquoise-blue glazed tiles caused a sensation. He also presented glazed stoneware tiles for the first time.

Universal Exhibition of 1889, Palais des Beaux-Arts, architect Formigé, turquoise-blue glazed tile dome by Muller Photo National Gallery of Art, Washington.

For the first time, he also presented enamelled stoneware, including a copy of the Frieze of the Archers[2] from the palace of Darius I in Susa (Persia) brought back to the Louvre by the Delafoy expedition in 1885-1886. This frieze was later supplemented by a decoration of columns and flower boxes with lions for the winter garden of a private mansion in 1893, before being offered by catalogue and invoiced according to the number of archers requested.

Frieze of the archers, after the frieze of the palace of Darius I in Susa (Persia) of the Louvre museum. Vestibule of the building 11 rue des Sablons in Paris. Photo by the author.

It was at the end of the exhibition that Émile Muller died on November 11, 1889. His son Louis (1855-1921), known as Louis d’Émile, succeeded him as head of the company, whose name became “Émile Muller & Cie”. While keeping the production of enamelled bricks and mechanical tiles at the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry, Louis d’Émile Muller opens up now fields of operations for the factory.

The Epidemic of Fake Bronze Subway Surrounds in the United States – Part Three: Past and Future

A good understanding of this article requires prior reading of the two previous articles. The first one deals with the fake subway surround sold by Bonhams in New York and the second with the other fake bronze surrounds known in the United States.

Let us recall that Guimard worked for the CMP[1] from 1900 to 1902. Starting in 1903, the company used his models to equip accesses of different widths with orthogonal bottomed uncovered surrounds as well as secondary accesses, the last of which were installed in 1922. In all, 167 Guimard structures were created[2]. In 1908 the first removal of an access was recorded. Episodic in the twenties, the dismantling of Guimard accesses then multiplied and their number recorded a first peak in the thirties. After the end of the Second World War and the taking over of the CMP by RATP in 1945, removals slowly resumed in the 1950s and soared in the 1960s. A first protection order at the ISMH (historic monuments directory) in 1965 only concerned a small number of accesses and it was not until 1978 that full protection was finally granted to them. By that time, 79 Guimard accesses had been dismantled. Many of the remaining uncovered areas had their fragile portals replaced by a Dervaux candelabra. In the absence of parts in stock from the Guimard structures that had been dismantled decades ago, the maintenance of the remaining accesses necessitated, as early as 1976, the ordering of new parts made by overmoulding at the GHM foundry. This process induces a slight shrinkage of the copies due to the shrinkage of the metal during the cooling that follows casting. From 1983 onwards, a new generation of cast iron is produced with exact dimensions by creating new models in cast aluminum. It was finally in 2000 that RATP carried out a complete restoration campaign of the Guimard accesses, restoring them to the appearance they have today.

State of the surrounds of the Europe station before the restorations of the year 2000. The portal was knocked down and replaced by a Dervaux candelabrum on the left. Photo RATP.

State of the surrounds of the Europe station after the restorations of the year 2000. The portal was restored using a copy provided by the GHM foundry and a new enameled lava sign provided by the Pyrolave company. Photo by the author.

Common characteristics of false bronze surrounds

All the copies of bronze surrounds discussed in our two previous articles (we exclude the one from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.) show strong similarities between them. These surrounds never include the original base stone. They are always found with an orthogonal base and never with a rounded base[3]. While the number of modules in length is variable and sometimes incomplete, the number of modules in width is always three — the most common configuration on the Parisian network— which corresponds to a hopper of about three meters and makes it possible to determine the width of a sign holder. The upper part of the sign holder of these surrounds has a slightly rounded shape, which we will come back to later but which determines an increase in the height of the sign. These surrounds never contain the original sign (whether it is made of enameled lava or red sheet metal with stencil letters), which would be expected when dismantling an old surround. In two cases, the sign is made of painted sheet metal with a discordant lettering (red sheet metal with white lettering such as the big M for Toledo; yellow sheet metal with green lettering such as the big M for the Phillips sale in New York). The Houston surround is made of two copper alloy plates, painted and riveted on an iron rim with a correct but approximate large M surround lettering. In the case of the Bonhams sale the sign is simply missing.

The detailed photos provided by the Bonhams auction house showed us the initial appearance of the painting of these false surrounds.

Detail of the right pillar and arch surround the Bonham sale in New York in 2019. Photo Bonhams.

But a more precise study is provided by the state report of the Houston surround written by Steven L. Pine in 2002. It mentions a first coat of burnt Sienna earth-colored paint on the bronze, then the concomitant use of a dark chrome green paint and a white paint for the reliefs. This first paint application is probably the one that prevailed for most of the false bronze surrounds since we find it almost on the corner post of the Chayette & Cheval sale in 2019. The forgers did not push the abnegation to the point of multiplying the repaints, whereas the old elements of the Paris subway have undergone over the years multiple painting before their restoration in 2000 when they were stripped and repainted[4]. For the surrounds of Toledo and Houston, exposed outside, a new, more recent painting was carried out. The one in Houston is covered with green epoxy paint enhanced with white on the reliefs.

Why bronze?

The Epidemic of Fake Bronze Subway Surrounds in the United States – Part Two: Other Known Bronze Copies

The uncovered bronze subway surround sold in 2019 by Bonhams in New York City was in fact the fourth fake surround of this nature that we have been informed of, all of which are present on American territory. We present them below in the order in which they came to our knowledge but which is not the chronological order in which they were manufactured and sold.

Phillips Sales in New York

The first bronze copy is an incomplete uncovered surround comprising a portal and only nine modules. It was sold on May 24, 2007 by the Phillips Auction House in New York on Liveauctioneers. Estimated at $450,000 to $550,000, it was sold for $340,000[1], At that time we did not know that its modeled pieces were made of bronze.

Uncovered surround comprising nine modules sold in New York by Phillips Live Auctioneers on May 24, 2007. Internet photo.

We thought we had lost sight of it when we recently received the photo below, taken at the Driehaus Museum in Chicago.

The Epidemic of Fake Bronze Subway surrounds in the United States – Part One: An Auction that Flops

This series of three articles develops an aspect dealt with in the book Guimard L’Art nouveau du metro, published in 2012 by La Vie du Rail. In it, we use the terms “old” or “authentic” Paris metro surrounds, “copies” and “fakes”, which must first be explained. We consider as “authentic” or “old” the surrounds and ædicula of the Paris metro whose elements have been edited according to Guimard’s models from the creation of the metro in 1900 until after the First World War in 1922. However, the Guimard metro entrances currently present on the Parisian network are only partly authentic because many of them have undergone more or less complete restorations since 1976, which consisted in replacing missing elements with copies. These were reissued first by overmoulding, then with new moulds with exact dimensions. It is with these copies of elements that in recent years the RATP (the Paris metro company) has supplied complete surrounds to metro companies in various foreign cities (Lisbon, Mexico City, Chicago and Moscow). These are copies of surrounds, but not “fakes” in the legal sense of the word, since there was never any question of passing them off as old Parisian surrounds. However, we will look at a series of copies of surrounds that are indeed fakes because they were created with the intention of selling them as authentic.

In March 2019 we were contacted by the representative in France of the American branch of a well-known British auction house: Bonhams. They suggested that we give our opinion on an “exceptional Guimard ensemble” and that we write the presentation leaflet for its sale scheduled for June 2019 in New York. Sensing what it could be about and contrary to our usual practice, we responded favourably to this request. We then received confirmation that it was indeed a new Parisian subway surround that was being sold in the United States.

Portal of the subway surround sold by Bonhams New York in June 2019. Photo Bonhams.

Section of a railing of the subway surround sold by Bonhams New York in June 2019. Photo Bonhams.

As we are beginning to have some experience with the “new-parisian-subway-surrounds-being-sold-in-the-U.S.A. ” and not wishing to show our hand at this point, we immediately asked Bonhams New York for more information.

The first thing we wanted to clarify was the nature of the metal used for the shaped parts of the surround. As we expected, we were told that they were made of bronze. This fact alone implied that these pieces had been overmoulded and cast in a material other than the original pieces (1) and that the railing was therefore a copy.

We also asked for additional photos, focusing on points where we were pretty sure we would find something to comment on. The photos provided to us supported the copy hypothesis by showing that some of the modelled pieces had a different aspect from what they should have and that their assembly suffered from errors and approximations.

In addition to the requested photos, Bonhams Auction House provided us with two documents:

– a copy of an inventory, undated, written by Mr. Dean P. Taylor in Fresno, California, and addressed to Mr. Joe Walters in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

– a certificate of authenticity drawn up in English by the French expert Mr Nicolaas Borsje on 9 July 1993. It refers to a metro surround purchased by Mr Arnold P. Mikulay in 1991.

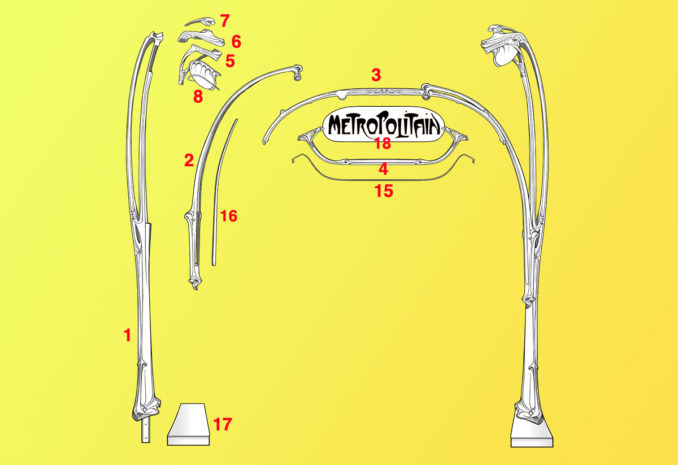

In order to facilitate the description of an uncovered surround, we recall below the names we have given to its constituent parts:

1- pillars (cast iron).

2- arches (cast iron).

3- upper sign holder (cast iron).

4- lower sign holder (cast iron).

5- stirrups (cast iron).

6- helmets (cast iron).

7- crests (cast iron).

8- signaling bowls (originally in blown-moulded glass then replaced by moulded synthetic material).

Elements of an uncovered Paris subway surround by Guimard. Author’s drawing.

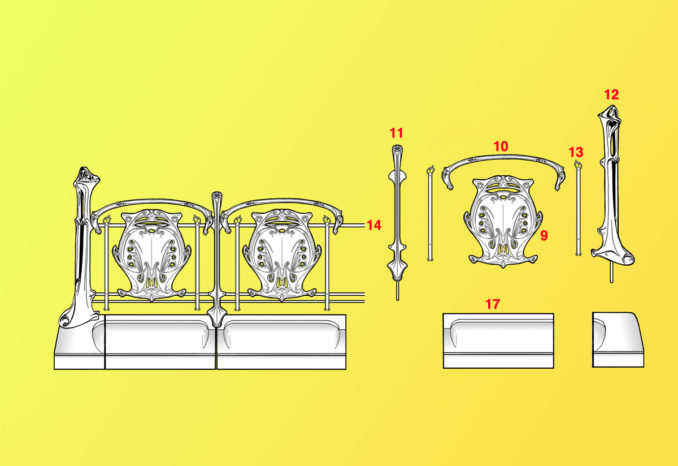

9- badges (cast iron).

10- hoops (cast iron).

11- middle posts (cast iron).

12- corner posts (cast iron).

13- flames (U-shaped irons made of rolled steel, cut and bent at the ends).

14- irons (U-shaped irons made of rolled steel).

15 & 16- blades (rolled steel bars).

17- base stones (Comblanchien).

18- sign (enamelled lava).

Elements of an uncovered Paris subway surround by Guimard. Author’s drawing.

So we sent Bonhams Auction House the following sales pitch: