Category: News

Hector Guimard’s participation in the 1925 Exhibition of Decorative Arts– Part 2

23 September 2025

After discussing the interiors of the town hall through its fixed decor, we continue our presentation with a look at its furniture. We will then turn our attention to the French Village cemetery, for which Guimard designed two funerary monuments. This is an opportunity to highlight the small chapel, a unique work that has long escaped the attention of researchers. Finally, we will conclude this study by discussing the reuse of a remnant of the town hall, which itself served as inspiration for the construction of another town hall a few years later.

The town hall furniture

Fifteen years ago, the discovery of a pair of chairs identical to those that furnished the town hall was the starting point for our research into this furniture and its supplier, EAGLE, a furniture manufacturer based in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine district of Paris[1].

Chairs of the town hall of the French Village oak, leather cover and modern nails; Private collection.

The appearance of a new piece of furniture by Guimard is always a small event in itself. While a new piece naturally enriches the reasoned catalogue of the architect’s furniture (currently in progress), it is also the best way to train our eyes and broaden our minds to furniture that we would not necessarily have associated with Guimard a few years ago. These chairs are a good example.

With a fairly simple overall design, they feature two distinct parts: a simple, unadorned seat contrasts seamlessly with a curved backrest that showcases the bulk of the cabinetmaking work. The only sculptural elements on the lower part are fine grooves that highlight the front legs along their entire height. The more complex design of the backrest leaves no doubt as to its creator: the ribbing and stretching of the material, the pointed “ears,” and the notched upper crossbar all refer to Guimard’s style.

These chairs are similar to a model of armchair, a photo of which can be found in the collection donated by the architect’s widow to the library of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. It was probably intended for the Nozal-Pezieux family, as a coat of arms clearly bearing the stylized initials NP adorns the upper crossbar of the backrest. This feature is also found on the chairs in the town hall, where there is an identical space for the initials.

Armchair with the crest Nozal-Pézieux, Bibliothèque des Art décoratifs, donation by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulmes

For EAGLE, participating in an event such as the 1925 Exposition required a significant investment, but one that was ultimately quite reasonable given the foreseeable economic benefits and expected gains in terms of image. Clearly, the company had no shortage of resources, having taken over an entire building in the heart of Faubourg Saint-Antoine. This high local visibility was reinforced by major, regular advertising campaigns in several national daily newspapers and specialist magazines.

By partnering with Guimard and supplying furniture for one of the main buildings in the French Village, the brand may also have wanted to benefit from the architect’s reputation. Although we do not know how Guimard came into contact with this company, he was undoubtedly impressed by the quality arguments put forward and detailed in the brand’s catalogs. These catalogs explain that “the furniture was manufactured in large quantities in two factories in Vincennes, while preserving the artistic aspect of its manufacture,” then finished in Paris “by master craftsmen in workshops adjacent to the stores on the Faubourg Saint-Antoine.”[3]

Deprived of his workshops since World War I, Guimard had to find a low-cost supplier who was nevertheless capable of producing (or reproducing) high-quality furniture. The architect already had connections in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, as a contract with one of its manufacturers had almost been signed before the war[4]. He therefore naturally turned to this neighborhood, where supply was still abundant.

Commercial flyer of the EAGLE company.

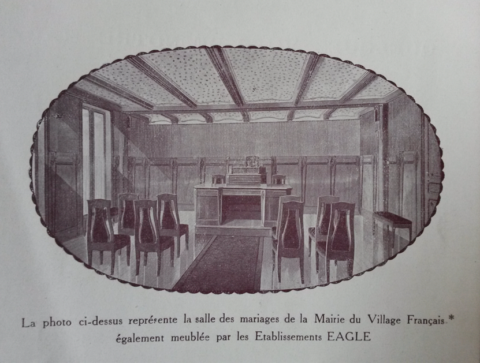

The photo of the wedding hall shows the mayor’s desk surrounded by two chairs, probably intended for the deputy mayors, while a third seat, perhaps an armchair, raised and decorated with a medallion, seems perfectly suited to accommodate the mayor.

The Mayor’s desk. GrandPalaisRmnPhoto. All rights reserved.

The stylized letters “R” and “F” on the upper band recall the official function of the premises. They brighten up a structure with massive, geometric lines, softened only slightly by the slanted corner motifs, which echo the design of the ELO paneling and reinforce the unity of the decor according to a principle dear to Guimard. The architect did not usually employ such an angular, almost rustic style, even in the mid-1920s. The explanation certainly lies elsewhere, as the main feature of this office was its modularity.

A detailed examination of the photo reveals that the office was in fact a set of independent pieces of furniture placed on a platform. Apart from the three chairs, which were by definition movable, it consisted of a large rectangular desk that could be used by the mayor for day-to-day administrative tasks and a recessed lectern, itself placed on another small platform intended for the mayor’s chair. This second part could certainly be used independently of the rest, for example for a speech. The complete configuration as it appears in the photo would therefore correspond to a situation in which the mayor would preside over a city council meeting alongside his two deputies.

Unable to afford a more refined set, Guimard opted for simple, functional furniture that could be easily adapted to life in a city hall.

The lack of photos of the other areas of the town hall or drawings of its furniture means that we do not yet know the exact size and location of this furniture, although we assume it to be fairly modest. However, we have found some answers in the advertising campaign launched at the time by the EAGLE company and in its catalogs published at the same time.

The 1926 catalog reveals an artist’s impression of the town hall’s wedding hall. Although fanciful in some respects—the stained glass windows that occupied the entire left side wall, for example, have been replaced by separate windows—the illustration is precise enough that the chairs and the mayor’s desk are easily recognizable, as are the ELO paneling and speckled ceiling as they appear in photos of the time. The artist even took care to include the Lustre Lumière wall lights that adorned the four corners of the room.

Extract of the ELO catalogue, 1926. Collection BnF.

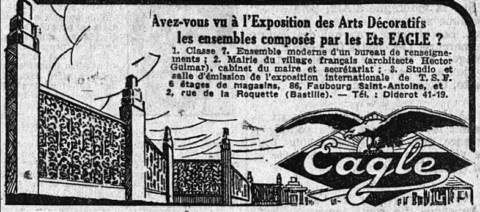

The presence of a bench on the right suggests that additional or complementary furniture was probably scattered throughout certain areas or rooms of the town hall. Advertisements published in the summer of 1925 also provide some clues as to the location of the furniture. L’Intransigeant of August 22, 1925, for example, invited readers to visit “the Decorative Arts Exhibition featuring ensembles designed by EAGLE,” including “the mayor’s office and secretariat in the French Village town hall (architect Hector Guimard).”

Logically, the rest of the furniture was therefore located in the secretariat, the other administrative room in the town hall. The ensemble must therefore have comprised no more than a dozen pieces of furniture divided between the mayor’s office and the secretariat, which could be broken down as follows: six or eight chairs, two armchairs, two desks, and perhaps a few side benches.

Advertisement for the EAGLE bran, L’Intransigeant, 22 August 1925. BnF/Gallica.

For both economic and stylistic reasons, Guimard drew on his earlier work, asking the EAGLE company to reproduce, in a simplified form, a chair model whose rather sober design, even for the 1900s, was compatible with the decor and architecture of the 1920s (at least that of his town hall). The mayor’s desk and lectern are therefore probably the only truly original creations in this set of furniture.

The French Village cemetery

For visitors to the French Village, the chances of bumping into a mayor in the corridors of the town hall were as slim as the risk of encountering a ghost or will-o’-the-wisp in its cemetery, since no one was buried there. However, it seems that the atmosphere of the place inspired a few vocations. An amusing anecdote published in the press recounts the arrival of a visitor at the general secretariat of the Exhibition, who, in all seriousness, requested a perpetual concession in the small cemetery…[4].

About ten days before the official inauguration of the French Village as a whole, the newspaper Excelsior reported on the inauguration of its cemetery on June 4, 1925, illustrating its article with a photo taken during the ceremony. Standing slightly behind the four officials, a fifth figure in profile, tall and thin, with a white beard, holds his hat in his left hand. Hector Guimard is easily recognizable, seemingly listening attentively to the comments of his companions for the day.

Inauguration of the cemetery of the French Village, Excelsior, 05 June 1925. BnF/Gallica.

Among the personalities present that day was the all-powerful president of the French granite producers’ union, Edmond Pachy, who had spared no effort to install a cemetery—a first for an installation of this scale at an international exhibition—which had inevitably sparked some comments in the press, at best amused, often skeptical of this commercial exercise, which was morbid and questionable to say the least… With considerable resources at his disposal, the source of which was easy to imagine in the aftermath of the First World War, Pachy had succeeded in mobilizing several major funeral companies around this project, as well as some big names in modern art.

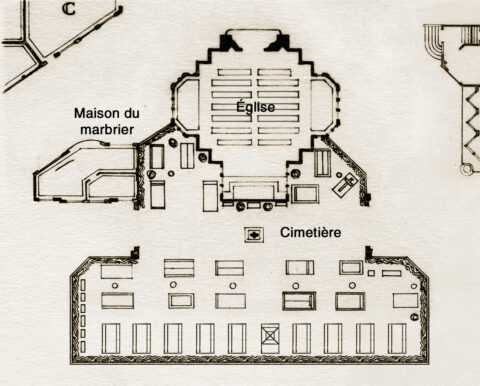

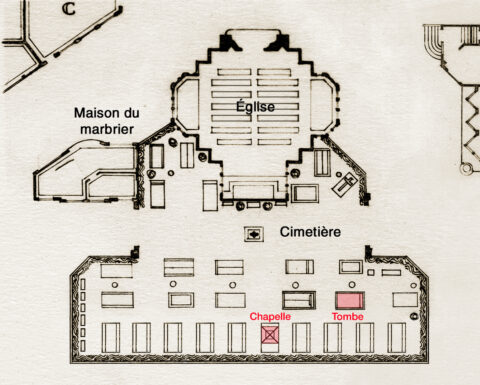

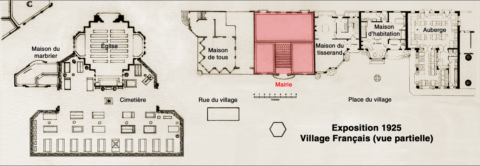

The cemetery occupied a small space at the foot of the church apse and, as was fitting, close to the home of the stonemason of architect Louis Brachet (1877-1968).

Partial plan of the French Village centered on the cemetery drawn according to the plans of the portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Rassemblés par Pierre Selmersheim, éditions Charles Moreau, 1926 and of our own research. Photomontage and drawing F. D.

Louis (Félix) Bigaux (1858-1933), who designed the cemetery, also created several tombs and, most notably, the bush-hammered granite entrance to the cemetery, which was crafted by the French Granite Producers’ Union and built by its members.

Entrance of the cemetery of the French Village by Bigaux. Portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Rassemblés par Pierre Selmersheim, éditions Charles Moreau, 1926, pl. 9. Private collection.

The cemetery contained around thirty funerary monuments, including a calvary and a chapel[5], all designed in a modern style. These included works by Bigaux, Roux-Spitz, Lambert, Dervaux, Victor Prouvé, the Martel brothers, and of course Guimard.

Funerary monument by the architect Roux-Spitz. La Construction moderne, 19 July 1925. Private collection.

The presence of two works by Guimard in the French Village cemetery could be perceived as post-war opportunism. This motivation is undoubtedly real, both for Guimard and for his colleagues involved in the cemetery, but it must also be put into context, bearing in mind that the construction of tombs was an integral part of the architect’s profession. When they had the means, after building their homes, families often entrusted their architects with the construction of their final resting places. However, this personalized activity tended to decline during the 20th century, as the bourgeoisie gradually turned to manufacturers offering standardized products. As far as Guimard is concerned, the fact that we have an increasingly comprehensive knowledge of his work means that we now have a fairly complete picture of his activity in the funerary field. He began very early on, and although his work seems significant to us, we do not yet know whether it was a particular interest of his or whether it was typical of his colleagues, among whom it is not so prominent. Nevertheless, we lean towards the former hypothesis, given the architect’s sustained and regular efforts in this field throughout his career. In any case, this activity reflects the evolution of his style, even if he sometimes had to compromise with the wishes of his clients.

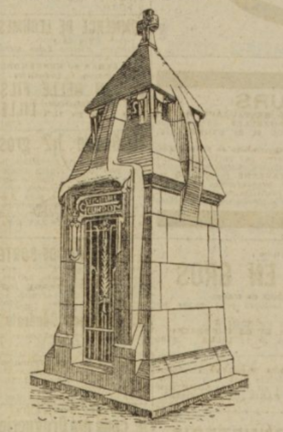

His most famous (and undoubtedly most spectacular) tomb is that of the Caillat family at Père-Lachaise, but his work also included tombs, small chapels, and funerary or commemorative monuments.

Caillat grave at the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris. Photo author.

The Decorative Arts Library collection also contains a number of photographs of funerary monuments, which were probably intended for inclusion in a catalog.

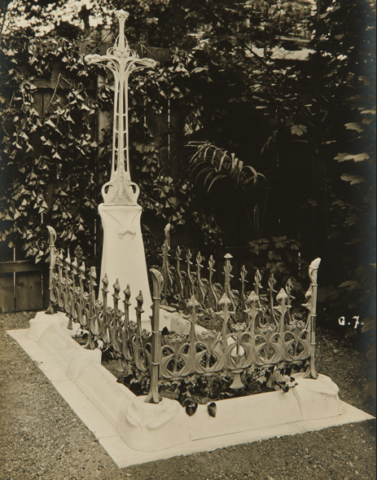

Fake tomb incorporating a GA cross, two GB bouquet-bearing pilasters, two GB posts, a GF planter, mesh and chain links, c. 1910. Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs. Donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Another series of later photographs shows simplified, fake monuments photographed outdoors. We can assume that they were part of an exhibition or presentation at a funeral company. These examples show that, more than ever, even in the funeral sector, Guimard intended to distribute his work in to reach a clientele who could not afford a unique creation but wanted the graves of their deceased to have a modern artistic touch.

Fake tumb incorporating a GB cross and surround. Bibliothèque des Arts décoratifs. Donation by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Guimard drew heavily on his catalog of cast iron designs published by the Saint-Dizier foundry from 1908 onwards. Several plates relate to funerary ornamentation: pilasters and grave surrounds, crosses of all sizes, wreath holders, coffin handles, and chain links. Curiously enough, none of these items were included in the French Village cemetery. No doubt their style was considered too dated.

Guimard’s two new creations for the French Village cemetery thus complete the long list of works he devoted to this field[6].

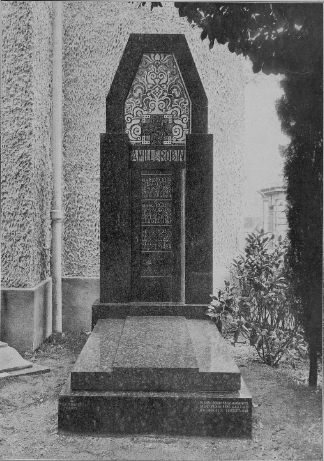

His involvement in the French Village cemetery is attested to by an early funerary monument that won a gold medal. An old postcard, published for promotional purposes by the tomb manufacturer Admant-Buissont, celebrated this award.

Funerary monument at the cemetery of the French Village. Ancient postcard. Private collection

Apart from perhaps the upper part of the stele, where a light sculpture frames the identification of the deceased (or a possible epitaph), almost nothing betrays the identity of its creator. The jury seems to have taken great pleasure in rewarding Guimard’s ability to simplify his style to the extreme, as this tomb is probably the simplest and most unadorned work of his entire career!

The background of the postcard illustration was a valuable source of information in locating the tomb within the cemetery and helping us to establish its layout. On the left, we can see the façade of the Maison de Tous, in the center behind Guimard’s tomb, the monument sculpted by Émile Derré (1867-1938), and even one of the three lava stone fountain terminals scattered throughout the French Village, which can be glimpsed behind the tree to the left of the tomb[7].

Guimard’s second creation for the French Village cemetery long escaped the attention of researchers, to the point that its existence was questioned. To our knowledge, no book or article entirely devoted to this section of the French Village has been published, so at first we had to make do with fragmentary and often imprecise information scattered throughout the press of the time.

The Official General Catalog does mention the presence of a chapel within the cemetery, but without providing any further information. The Hachette guide to the Exhibition is much more precise, detailing some of the works and their creators. We learn that “(…) Mr. Hector Guimard built a small chapel whose appearance highlights this architect’s very characteristic evolution towards less complicated forms, but always in perfect balance”[8].

In the literature devoted to Guimard, several hypotheses have been put forward, sometimes with supporting photographs, but without convincing readers[9].

Furthermore, none of the monuments related to the cemetery published in the press at the time or in public collections correspond to the definition of a funeral chapel[10].

This situation persisted until the discovery of new autochromes in the collections of the Albert Kahn Museum. In several photographs relating to the French Village cemetery and dated July 1, 1925, a tall, compact shape stands out against the light. Although the photo is dark, the overall composition of the building catches the trained eye and could correspond to the description of the Guimard chapel in the Hachette guide.

View of the cemetery of the French Village autochrome. Musée départemental Albert-Kahn, Département des Hauts-de-Seine.

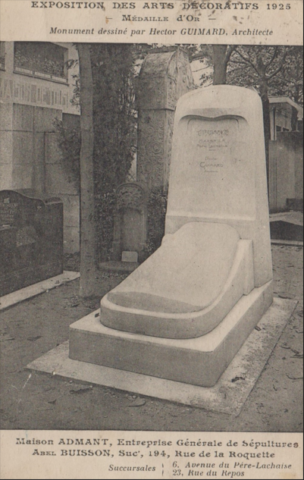

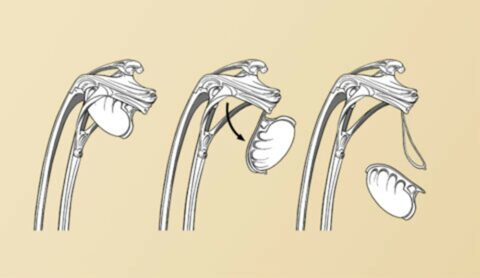

At the same time, Marbreries Générales Gourdon launched a major advertising campaign to promote a new model of funeral chapel on display at the “Modern Village Cemetery,” accompanied by an illustration[11]. Presented from a different angle, showing the main façade and its entrance closed by a wrought-iron door, the monument is easily recognizable with its uprights rising halfway up three of the four façades and enveloping an original double openwork roof system. The treatment of the entrance—whose masonry stands out clearly from the monument—is even more characteristic of Guimard’s work. From the upper lintel of its frame springs a fourth upright, which also joins the small capital crowning the chapel and supporting the cross at the top.

The chapel of the French Village. L’Écho du Nord de la France, 12 août 1925. BnF/Gallica.

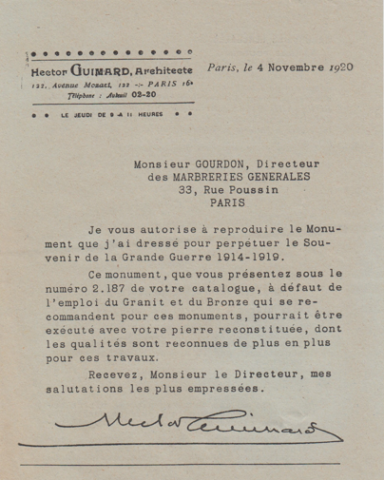

Curiously enough, but perhaps as a result of an agreement (or a dispute…), the advertisements do not mention Guimard, even though the company was well acquainted with the architect. In the aftermath of World War I, Marbreries Générales Gourdon sent out advertising leaflets and catalogs accompanied by a facsimile of a letter on the architect’s letterhead and signed by him.

Fac-similé of a letter by Guimard attached to the catalogues of the Marbreries Générales Gourdon.

Private collection

Thanks to these new discoveries, we have been able to finalize the cemetery map with the location of Guimard’s two monuments. We take this opportunity to launch a search for these two works, which were certainly located in the alleys of a (real) cemetery.

Map of the cemetery of the French Village drawn from the plans of the portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Rassemblés par Pierre Selmersheim, éditions Charles Moreau, 1926 and from our research. Photomontage and drawing F. D.

Remains and legacy

Some parts of the Exposition were quickly demolished after it closed, while others remained standing for several months for financial reasons, as no one wanted to bear the cost of demolition. Fortunately, a few works have survived to this day, sometimes on display in public spaces or added to private or museum collections.

The demolition of the French Village also took several months. It seems that the town hall was still standing in January 1926, as noted by several journalists who came to report on the demolition work. Guimard probably tried to offer the building to local authorities, but without much success, as far as we know, since the town hall did not survive the Exposition. However, it is entirely possible that some of the decorations and materials were reused elsewhere. Guimard himself reused at least one element, adapting it to a new configuration.

Main entrance door of the town hall of the French Village. Bibliothèque des Arts décoratifs. Donation Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

The entrance door of the building on Rue Henri Heine, built by Guimard, bears a striking resemblance to that of the town hall…

Entrance door to the building 18 rue Henri Heine, 75016 Paris. Photo author.

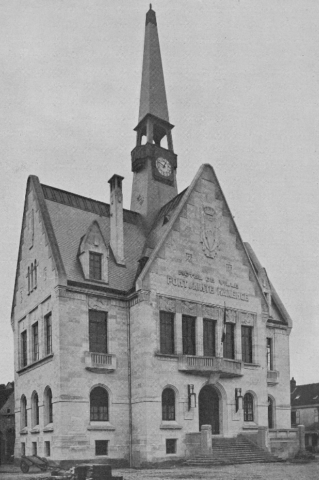

Although Guimard’s town hall did not enjoy a second life within a municipality, it nevertheless seems to have inspired the designers of the town hall in Pont-Sainte-Maxence (Oise), built in 1930. This hypothesis, put forward by Léna Lefranc-Cervo at the Hector Guimard study day organized last year at Paris City Hall, seems entirely convincing to us [12]. Triangular pediments on the facades, a spire set back from the pediment of the main facade, dormer windows on the roof… there are many similarities in the overall composition of the two buildings (and even in their interior layout). Furthermore, the fact that the three architects Marcel Jannin, Jean Pantinet, and Jean Szelechoivsk were members of the Society of Modern Architects (formerly the Group of Modern Architects founded by Guimard in 1923) also supports this assumption.

Town hall of Pont-Sainte-Maxence. La Construction Moderne, n°33, 18 mai 1930. Portail documentaire de la Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine.

However, the resemblance ends there, as the architects opted for a massive, angular building with no ornamental references to the Art Nouveau style.

Conclusion

Although Hector Guimard’s work in the aftermath of World War I did not receive the same attention as the first part of his career, it is nonetheless of real interest. The architect continued his work, charting his course with the same ideas while discreetly but significantly adapting them to the social context of his time. Resolutely committed to modern architecture and applied art, he always advocated the renewal of the decorative arts, a principle he put into practice by simplifying his style but at his own pace, cultivating his difference and repeating to anyone who would listen that fashion should not dictate art.

On April 9, 1930, at around 6:30 p.m., Hector Guimard sat down at the Eiffel Tower radio station for a short lecture on architecture and fashion. Explaining to listeners that “[…] the nature of fashion is to change rapidly. Architecture being by definition the art of building, which implies lasting works, the word ‘fashion’ is therefore a contradiction in terms in architecture,“ he denounced the austerity that he believed was rampant in architecture and the applied arts: ”I think, moreover, that the current fashion for the nude responds to a whole state of mind. We no longer believe in mystery; we want to immediately understand things that we can simply touch.”[13].

The gradual evolution of Guimard’s style was often misunderstood, with some observers of the time judging a little too quickly (even though they did not have all the explanations) that Guimard was stubbornly sticking to the 1900 style. But while the stylistic gap between him and his colleagues was still acceptable in the mid-1920s, it became untenable at the beginning of the following decade.

Olivier Pons

Notes

[1] Originally from the US, the brand specialized in mid- to high-end office furniture. Its arrival in France seemed fairly recent, as the first mentions of its existence date back to the early 1920s. The main store occupied a large space on Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Antoine, but EAGLE also had another store nearby on Rue de la Roquette and a branch in Lille.

[2] In addition to its presence at the French Village town hall, the brand exhibited in the information office section (class 7), for which it won a silver medal, as well as in the studio and broadcasting room of the International TSF Exhibition.

[3] EAGLE catalog from 1926. BnF collection.

[3] A draft contract between Guimard and the manufacturer Olivier et Desbordes, preserved in the Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard papers at the New York Public Library, provided for the small-scale production of “Guimard-style” furniture.

[4] Le Merle blanc of May 30, 1925 reports the visitor’s request: “Sir, I have come to ask you to grant me a perpetual concession at the cemetery of the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs. Of all the cemeteries, yours is my favorite. At Père-Lachaise, there are too many great men. The Montmartre cemetery is too close to the dance halls on the hill. Pantin and Bagneux are too far away for my friends. At the Passy cemetery, I would fear suffering the same tribulations as Marie Matskirsef [sic]. With your permission, I want to be buried in the Cours-la-Reine cemetery.”

[5] Official General Catalog. Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Posts and Telegraphs, 1925. Private collection.

[6] We have counted sixteen funerary and commemorative works, not including the drawings from the École nationale des beaux-arts and the unrealized project for a commemorative monument to the Victory of the Marne.

[7] L’Auvergne littéraire et artistique et félibréenne, July 1925. The students of the Volvic Departmental School had provided three lava stone drinking fountains. Two were located in the cemetery, while a third had been installed in the courtyard of the French Village school.

[8] Paris, arts décoratifs, 1925, Guide de l’Exposition, Librairie Hachette. Private collection.

[9] Georges Vigne, Hector Guimard, Éditions d’art Charles Moreau, 2003, p. 357. A photograph illustrating the article on the French Village cemetery is supposed to show Guimard’s chapel behind a sculpture by Théodore Rivière. This photo was actually taken at the Château de Nice cemetery. The sculpture representing the two sorrows is still in place and the chapel in the background is the funerary monument of a prominent Nice family.

[10] A funeral chapel is a monument that partly resembles a religious chapel but is less imposing. It is usually closed by a door and has a commemorative altar used for eulogies for the deceased. Coffins are either placed inside if the chapel is large enough, or underneath it (in the case of the Guimard chapel).

[11] La Dépèche (Toulouse), August 10, 1925; Le Grand écho du Nord de la France, August 12, 1925; L’Est républicain, August 11, 1925. The advertisement that appeared in the European edition of The New York Herald on October 7, 1925 provides some additional information. The chapel is built of granite from the quarries of Becon (Maine-et-Loire) and can be ordered for the sum of 56,000 francs (door and windows included).

[12] Hector Guimard study day organized at Paris City Hall on December 10, 2024, to mark the end of the Hector Guimard year.

[13] L’Ouest-Éclair, April 9, 1930. BnF/RetroNews.

Translation : Alan Bryden

Hector Guimard’s participation in the 1925 Exhibition of Decorative Arts– Part 1

7 September 2025

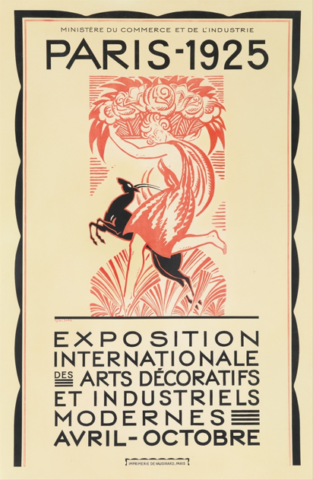

We are taking advantage of the celebrations marking the centenary of the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, held in Paris in 1925[1], to publish our research on Hector Guimard’s participation in this event. The architect’s relatively modest contribution is somewhat reflective of his career in the aftermath of the First World War. This period has ultimately been little studied, but the 1925 Exhibition was one of its highlights and undoubtedly one of its most interesting moments. Guimard’s participation took the form of three works in one of the exhibition’s sections called the French Village: the town hall and two funerary monuments. While we have a comprehensive study of the French Village currently underway, we have chosen to highlight some lesser-known aspects, such as the interiors of the town hall and the cemetery. We will begin by discussing the context that led to the organization of the exposition, Guimard’s role, and his participation in the debate of ideas on the eve of this major event for the decorative arts and architecture.

Driven by Art Nouveau in the 1890s, the revival of European architecture and decorative arts that began in the late 19th century reached maturity around 1910, then continued into the 1920s with what would retroactively be called the Art Deco style, reaching a spectacular climax in France with the 1925 Exhibition. The long gestation period of this event—which began twenty years earlier and was postponed several times, notably due to the First World War—was commensurate with its success (more than 16 million visitors) and its international impact, propelling France to the forefront of nations in this field.

The organizers’ stated ambition was to exhibit only new and modern works[2], so no space was given to older styles, which were confined to exhibitions outside the event, such as the one organized at the Galliera Museum[3]. Even though some observers recognized the contribution of the 1900 artists to modern art, the break with Art Nouveau was already largely complete. Among a few famous statements, that of the painter Charles Dufresne (1876-1938) summed up the general mood of the time quite well: “The art of 1900 was the art of fantasy, that of 1925 is the art of reason” … With a few exceptions, critics were therefore fierce towards Art Nouveau, often dwelling on its excesses and quickly forgetting that the architecture and decorative arts celebrated with pomp and circumstance in 1925 drew in part from the renewal that had begun thirty years earlier. It would take a decade before interest in Art Nouveau was rekindled and its rehabilitation and protection began to be considered[4].

Official poster for the 1925 Exhibition Priv.coll.

In 1925, among the names of participants who took advantage of the event to launch or consolidate their careers, such as Mallet-Stevens, Le Corbusier, Roux-Spitz, and Patout, others were already active on the art scene in the 1900s. A sign of a certain recognition, the presence in 1925 of Plumet, Sauvage, Dufrène, Follot, and Jallot was also proof of their ability to adapt and renew themselves. Two of them, Maurice Dufrène (1876-1955) and Paul Follot (1877-1942), were even at the head of decoration workshops in Parisian department stores (La Maîtrise at Galeries Lafayette for the former, Pomone at Le Bon Marché for the latter). The success of the high-quality Art Nouveau productions of these two great names in decoration at the turn of the century did not prevent them from shifting towards a more stripped-down style in the mid-1900s and then, in the 1910s, towards compositions in which curves had almost disappeared.

Hector Guimard’s situation was somewhat different from that of his colleagues. Although he had evolved his style towards greater simplicity and sobriety, he always refused to give in to fashion. On the eve of the 1925 Exhibition, he told a newspaper: “Let’s just be ourselves, impose the discipline of harmony on ourselves, without believing that Fashion can and should dictate Art[5].” We will return to this principle a little later, as it was a guiding principle of the 1920s that largely explains the choices made by the architect during this period.

At the beginning of this new decade, Guimard continued to focus primarily on architectural work, as the loss of his studios in the aftermath of the world war had greatly reduced his work in the field of decorative arts. However, the activism he still displayed in the early 1920s allowed him to retain a certain influence within organizations known for promoting new ideas and heavily involved in the genesis of the 1925 Exhibition. Thus, even though he no longer held any responsibilities within the Société des Artistes Décorateurs (SAD)[6], he was still a member in the early 1920s and even exhibited there in 1923[7]. It should also be noted that during his trip to the United States in 1912, Guimard had been commissioned by the SAD. He introduced himself to the Americans as vice-president of the association and promoter of “The International Exhibition of Modern Architecture and Decoration,” which was to be held in Paris in 1915[8]…

It was therefore as an expert on the subject and spokesperson for modern ideas in the run-up to the exhibition that he became a founding member of the Groupe des Architectes Modernes (GAM)[9], holding the position of vice-president alongside Henri Sauvage (1873-1932), under the presidency of the indispensable Frantz Jourdain (1847-1935).

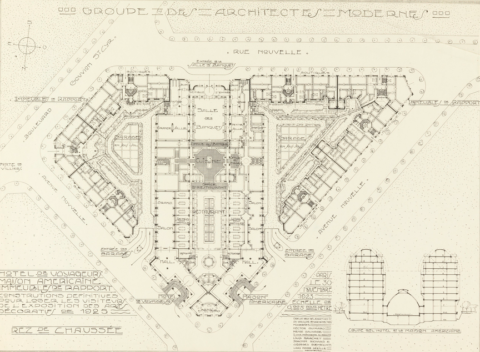

Letter from the Groupe des Architectes Modernes requesting the fee of 40 F from its members, dated 10 March 1928 and signed by Boileau. Coll. MOMA. All rights reserved

In the same interview in 1923, he justified its creation by the need to promote modern ideas that would undoubtedly be expressed during the upcoming event and, aware that the pavilions built would only have a short-lived existence, by the need to create an annex outside the 1925 Exhibition sponsored by the French State and the City of Paris “where modern architecture would be expressed, like jewelry, furniture, and fabrics, in definitive materials. These buildings would provide modern decorators with a living setting and industrialists with an initial outlet for their modern production, without which a reaction would be to be feared. Most of the pavilions built for the exhibition were indeed destroyed after the event, and this annex project never saw the light of day, nor did the ambitious project entitled “Travelers’ Hotel/American House/ Investment Buildings, permanent constructions for visitors to the 1925 Decorative Arts Exhibition,” which we know existed from three plans signed by several GAM architects, including Guimard, and which was to be located on Boulevard Gouvion-St-Cyr in Paris (75017).

Plan of the ground floor of the final building design by the Groupe des Architectes Modernes for the 1925 Exhibition, dated November 30, 1923. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. All rights reserved..

The GAM was ultimately entrusted with the creation of a section called the French Village within the exhibition. This could be seen as compensation, or even a way of keeping it at arm’s length, but the fact that several of its members were tasked with constructing some of the most important buildings at the event nevertheless confirms the association’s influence on the exhibition.

The French Village Town Hall

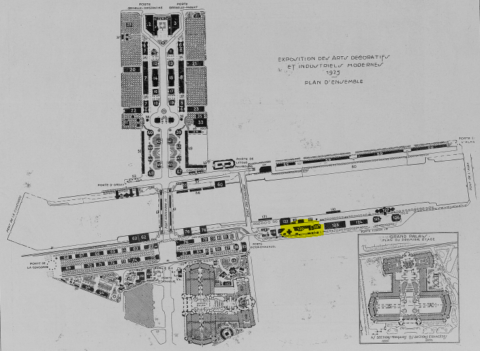

The French Village occupied a relatively small area around Cours Albert 1er, slightly away from the Esplanade des Invalides, which was considered the epicenter of the exhibition. Comprising some twenty buildings designed by as many architects from the GAM[10], the complex was a kind of architectural proposal intended to represent a village from the early 20th century.

Plan d’ensemble de l’Exposition de 1925 implantée de part et d’autre de la Seine. L’emplacement du French Village est surligné en jaune. La Construction Moderne, 03 Mai 1925. Coll. part.

In addition to the essential town hall, church, and school, there was an inn, a “bourgeois” residence, a community center, a bazaar[11], various commercial buildings, and several so-called secondary structures such as electrical transformers, a sanitary unit, and a wash house. Without exception, all these structures shared the common feature of having been built in a modern style.

Partial plan of the French Village based on plans from the portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Rassemblés par Pierre Selmersheim, published by Charles Moreau, 1926. Photomontage by F. D.

For economic reasons and due to constraints related to its environment, the ambition of the initial project had been scaled back. The architects had to work around existing plantings and connections to the sewer, water, gas, electricity, and telegraph systems. Furthermore, as the area ultimately allocated to the project did not allow for the construction of independent buildings, Dervaux had no choice but to make the buildings adjoined (with the notable exceptions of the church and the school). Most of them were therefore aligned lengthwise, parallel to the Seine. This revision of the initial project had the immediate effect of changing the name of the complex from “Modern Village” to “French Village,” as the GAM architects had been unable to demonstrate sufficient urban planning skills. It should be noted that this double name persisted, even during the exhibition, as some authors felt that the small village was modern enough to retain this description.

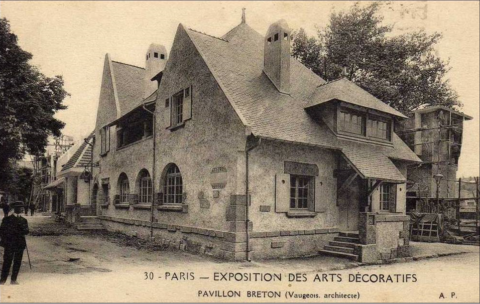

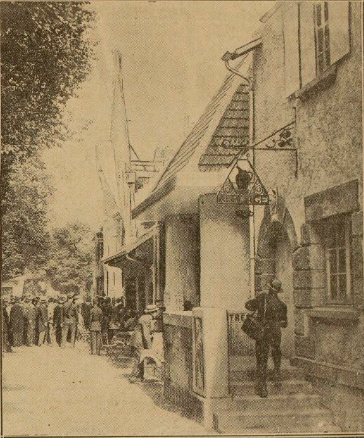

The Guimard town hall was one of the last buildings in the village to be completed (along with Pierre Patout’s (1879-1965) electrical transformer), even though the exhibition had been open for over a month[12]. Several old postcards show the building still under construction, despite the photographers’ efforts to hide it or relegate it to the background…

View of the French Village. In the background on the left, the town hall under scaffolding, as well as the Patout transformer on the right may be seen, ancient postcard. Private collection.

This delay in the construction of one of the main buildings in the small town probably explains its late inauguration. It was not until Monday, June 15, 1925, that the French Village was inaugurated, as shown in a photo in the Excelsior newspaper, in which the town hall appears to be free of scaffolding.

The inauguration of the French Village, Excelsior, 16 Juna, 1925 Bnf/ Gallica

With its back to the river, Guimard’s town hall stood at the edge of the village square, adjoining the” Maison de Tous” on its left, designed by the talented urban planner D. Alfred Agache (1875-1959), and the “Maison du Tisserand” by architect Émile Brunet (1872-1952) on its right. Agache perfectly summed up the spirit that guided the GAM in the construction of this complex: “(…) the “Village de France”, which we built in order to provide a snapshot of what a rural community should be, to meet the needs of modern life[13].”

The townhall of the French Village, ancient postcard Private collection .

Recognizing that they had been unable to construct separate buildings, the two architects took advantage of this immediate proximity to create an opening allowing circulation between the two structures[14], no doubt believing that the functions and roles of the two buildings were compatible and complementary.

The “Maison de Tous” and the Town hall of the French Village, ancient postcard, private collection

The exterior appearance of the building is well known thanks to numerous old postcards on which it is either the main subject or a secondary subject, with the eleven pinnacles punctuating the roof often making it impossible to miss in photographs. The building appears to be a synthesis of Guimard’s last pre-war works and his research in the early 1920s to develop an economical construction method called “Standard-Construction”, which was used to build the small hotel on Square Jasmin in the 16th arrondissement of Paris.

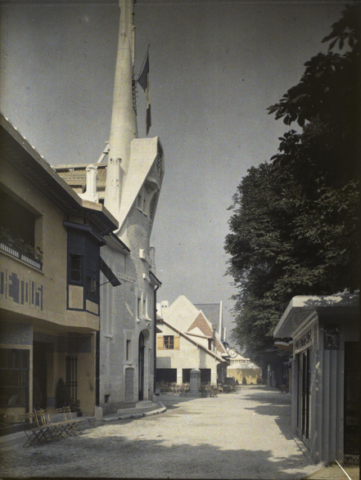

Adding a touch of originality to the group of buildings, the highest of these pinnacles rose directly above the central bay of the slightly curved main facade, punctuated by numerous openings, but set back from a cement canopy covering the clock. Like a signal, both in terms of its height and its function as a carillon, it symbolically rivaled the bell tower of the neighboring church built by architect Jacques Droz (1882-1955) and reminded visitors of the importance of republican life in a modern village… We also have a fairly accurate idea of its colors, as the Archives de la Planète at the Albert-Kahn departmental museum hold numerous autochromes of the event, in which the town hall appears in light tones due to its asbestos brick and white and gray stone cladding[15].

View of the French village. On the left, the Maison de Tous and the town hall, followed by the village square and then the inn; on the right, the fish market, autochrome. Albert Kahn Departmental Museum, Hauts-de-Seine Department

Two other sources are invaluable for learning about the town hall: the portfolio published by Pierre Selmersheim[16] and Anthony Goissaud’s article in La Construction Moderne[17]. A third unpublished article in Le Moniteur des Architectes communaux[18] still eludes us, but we hope that this publication will enable us to find it…

Main facade of the town hall, portfolio Architecture at the 1925 Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts/The Modern Village/Regionalist Buildings and Several Other Pavilions/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim, Charles Moreau Publishing, pl. 2, 1926. Private collection.

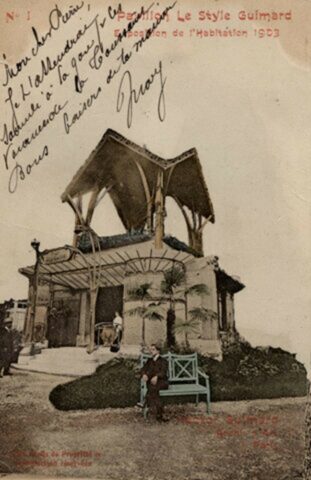

A postcard published for promotional purposes by Guimard (used to illustrate the header of this article) completed this editorial material. On the front is an illustration by artist A. C. Webb (1888-1975)[19]. The back comes in different versions depending on the intended use (advertising with a list of town hall employees, promotional material touting a construction technique, or blank for correspondence, etc.).

Rear facade of the town hall, portfolio Architecture at the 1925 Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts/The Modern Village/Regionalist Buildings and Several Other Pavilions/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim, Charles Moreau Publishing, pl. 3, 1926. Private collection

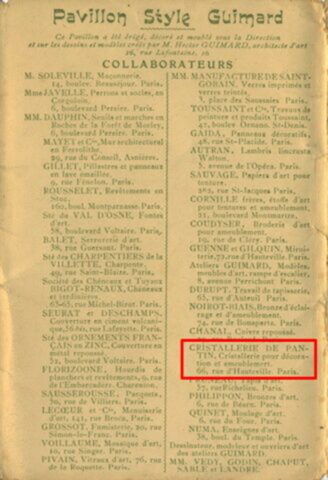

The panels framing the main entrance door, intended for municipal notices, were used here to showcase the companies and artists who collaborated on the town hall project. Among them were some more or less famous names, such as the Schenck family of ironworkers, who made the wrought iron staircase railing, the stained-glass artist Gaëtan Jeannin, who created the stained-glass windows in the wedding hall, and the painter René Ligeron, whom we will discuss later.

Finally, a collection of cast iron pieces from Guimard’s repertoire of models, produced since 1908 by the Saint-Dizier foundry, adorned the building, particularly on the rear facade, where there were balconies on the first floor and panels decorating the windows on the ground floor.

Details of the rear facade of the town hall decorated with cast iron. Library of Decorative Arts. Gift of Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

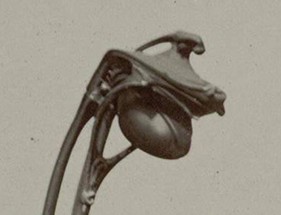

At the ends of the two facades, the downspouts from the Saint-Dizier foundry connected to gutters from the Bigot-Renaux foundry. These undecorated gutters were fitted with “outward-angled gutter ornaments” also from the Saint-Dizier foundry, which appear to have been used only here.

Details of the rear facade of the town hall decorated with cast iron. Decorative Arts Library, donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Fixed decoration

Among the companies that played an important role in the interior decoration of the building was ELO[20], whose fiber cement paneling covered part of the interior walls. This company experienced significant growth in the 1920s, when there was high demand for inexpensive decorative elements in all styles. As cost savings were a common denominator in most of Guimard’s buildings, it is not surprising that he called on this company for the town hall, given that the budget was particularly limited[21]. ELO paneling thus joined the long list of new materials (and sometimes new techniques) used by the architect throughout his career. The possibility of modeling them to his style was an additional advantage. Notable examples include the use of Lantillon fiberboard panels covering the ceilings of Castel Béranger, Castel Henriette, Villa Berthe, and the Lantillon pavilion in Sevran, as well as Garchey glass stone, also used at Castel Henriette, and ferrolithe, used on the rear façade of the Pavillon de l’Habitation in 1903 [22].

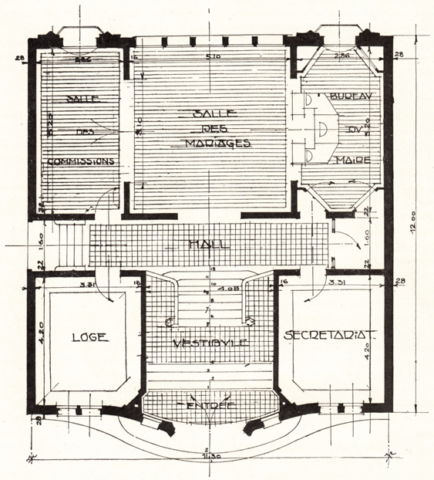

Plan of the town hall published in La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925. Private collection.

An exhibition devoted to the new materials and techniques used in the construction of the town hall occupied the large room on the ground floor, accessible only through two doors at the rear. Among those featured were Taté for plaster, stone, and marble; Lambert Frères for asbestos bricks; and the Société de Traitement Industriel des Résidus Urbains (Industrial Urban Waste Treatment Company)[23].

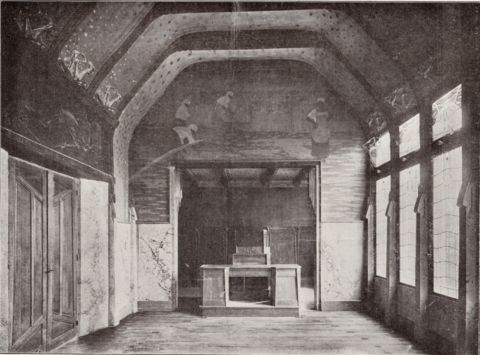

In the photo from La Construction Moderne, we can see ELO paneling covering part of the wall behind the mayor’s desk.

Wedding hall with the mayor’s desk in the background and Jeanneau stained glass windows on the right. La Construction moderne, November 8, 1925. Private collection.

Public collections, meanwhile, hold another photograph that allows us to appreciate the wood paneling sculpture in the foreground.

Wedding hall and the mayor’s desk. GrandPalaisRmnPhoto. All rights reserveds.

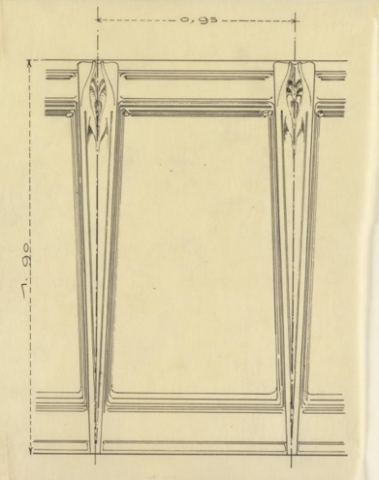

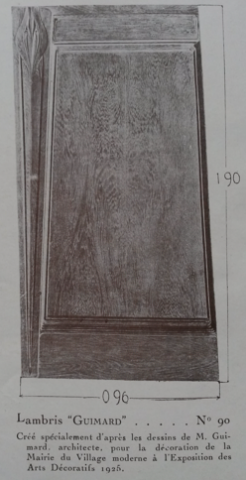

Finally, the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum holds the original and almost definitive design for the paneling. A subtle and delicate blend of the organic and plant worlds, the main motif takes us back twenty years, bringing a touch of sentiment dear to Guimard and open to interpretation.

Drawing of the town hall paneling. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. All rights reserved.

This paneling would appear under the name “Lambris Guimard” in the following year’s ELO catalogs. This was probably the architect’s last attempt to market a model commercially.

« Lambris Guimard », catalogue of the ELO company, 1926. Coll. part.

ELO is also likely the maker of the striking bas-relief featuring vultures above the doors to the wedding hall, signed by Raymond Andrieux. Although birds of prey—alongside wild animals—were among the favorite subjects of artists of the time, one might wonder why they were chosen to adorn the wedding hall.

Detail of the frieze depicting vultures by R. Andrieux decorating the wedding hall. GrandPalaisRmnPhoto. All rights reserved.

Although Guimard undoubtedly met this virtually unknown artist through the ELO company—or perhaps it was the other way around—he may have wanted to seize the opportunity to promote a young artist while adapting an existing work at minimal cost. Information about Raymond Andrieux is very scarce[24], but we have found a trace of a work, now in a private collection, whose resemblance to the bas-relief at the Town Hall is particularly striking.

ELO panel with vultures signed R. Andrieux on the lower right and bearing the ELO company stamp on the reverse, width 1.37 m, height 1.15 m, depth 0.18 m. Private collection.

Our investigation led us to the 1924 Salon des Artistes Français, where Andrieux exhibited a panel in the Decorative Arts category under the caption: “Vultures, fiber cement panel”[25]. This work therefore certainly served as a model for the bas-relief in the wedding hall, with Guimard probably asking the young artist to draw inspiration from his 1924 work and adapt it into a frieze. It is even possible that this work appeared in the manufacturer’s catalog, but the copies we have do not mention it.

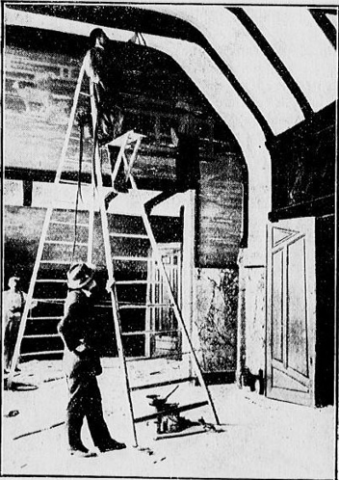

Among the other artists who collaborated on the interior decoration of the building was René Ligeron (1880-1939)[26], whose two paintings depicting scenes of the French countryside—a decorative theme found in many town halls—adorned the walls of the gables of the wedding hall. Thanks to the previous photos, we were familiar with the painting entitled Harvesters binding sheaves. A third, previously unseen view of the wedding hall being decorated gives a glimpse of the second work, entitled Woman guarding sheep, in the same rural style as the first.

The wedding hall of the town hall of the French Village under decoration Recherches et Inventions n° 163, mars 1928. Private collection

It is not impossible that the figure in profile with a gray beard, wearing a hat and standing on a ladder, is Hector Guimard himself, who came to supervise the work…

(to be continued)

Olivier Pons

[1] The event took place from April 28 to November 8, 1925. For convenience, we will refer to it as the 1925 Exhibition or simply the Exhibition.

[2] The rules stipulated: “(…) works of new inspiration and genuine originality, executed and presented by artists, craftsmen, industrialists, designers, and publishers, and falling within the scope of industrial and modern decorative arts, are eligible for admission to the Exhibition. Copies, imitations, and counterfeits of ancient styles are strictly excluded.” Exhibition rules. Private collection.

[3] “Exhibition of the Renovators of Applied Art from 1890 to 1910,” Galliera Museum (Paris), June 6 to October 20, 1925.

[4] See the article by Léna Lefranc-Cervo: https://www.lecercleguimard.fr/fr/proteger-le-patrimoine-art-nouveau-parisien-initiatives-et-reseaux-dans-lentre-deux-guerres/

[5] Interview given to L’Information financière, économique et politique, February 19, 1923. BnF / Gallica.

[6] The Société des artistes décorateurs (Society of Decorative Artists) was founded in 1901 on the initiative of lawyer René Guilleré and several other leading figures in the decorative arts. Its aim was to “promote the development of the decorative arts,” as stated in Article 2 of the SAD’s statutes, “approved by order of the Prefect of Police on April 6, 1901.” Private collection.

[7] The catalog failed to mention his name, but his participation in the 1923 SAD is confirmed by several articles. For example, the January 1923 issue of L’amour de l’Art mentions the three tombs presented by Guimard, including “that of the Henri family,” a unique monument that undoubtedly still exists and which we are actively searching for…

[8] See the article: https://www.lecercleguimard.fr/fr/le-premier-voyage-dhector-guimard-aux-etats-unis-new-york-1912/

[9] See the article by Léna Lefran-Cervo: https://www.lecercleguimard.fr/fr/entre-norme-et-liberte-larchitecture-du-point-de-la-vue-de-la-societe-des-architectes-modernes/

[10] It was built under the direction of architects Charles Genuys (1852–1928) and Gouverneur, based on an overall plan designed by Adolphe Dervaux (1871–1945). See Lefranc-Cervo, Léna, Le Village français: une proposition rationaliste du Groupe des Architectes Modernes pour l’Exposition Internationale des arts décoratifs de 1925, research thesis (2nd year of 2nd cycle) supervised by Alice Thomine Berrada, École du Louvre, September 2016.

[11] The bazaar was built based on plans by architect Marcel Oudin (1882-1936) for the Magasins Réunis chain. A specialist in reinforced concrete construction, Oudin had become one of the architects of the Corbin family from Nancy, owners of the Magasins Réunis in eastern France, but also in Paris (Magasins Réunis République, À l’Économie Ménagère, Grand Bazar de la rue de Rennes).

[12] In an original photo dated June 1, 1925, the town hall still appears to be covered in scaffolding.

[13] La Cinématographie française, April 11, 1925. La Maison de Tous, which was initially to be called Maison du Peuple (House of the People) – a name considered too connotative – was undoubtedly one of the most attractive buildings in the Village, both in terms of its architectural design and the ideas behind its conception and deserves a full article.

[14] Le Journal des débats politiques et littéraires, June 17, 1925.

[15] An article devoted to Guimard’s use of bricks is in preparation and will provide a more complete overview of the materials used in the French Village town hall.

[16] Architecture at the 1925 Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts/The Modern Village/Regionalist Buildings and a Few Other Pavilions/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim. Charles Moreau Editions, 1926.

[17] “The Town Hall of the French Village,” A. Goissaud, La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925.

[18] “La Mairie du Village français à l’Exposition,” Le Moniteur des Architectes communaux, 1925, no. 2.

[19] Alonzo C. Webb (1888-1975) was an American painter and engraver who spent his life between the United States and Europe. After studying architecture and fine arts first in Chicago and then in New York, he moved to Europe after World War I and settled in France in the 1920s, where he produced drawings of ancient monuments and landscapes for advertising and to illustrate articles in major national newspapers (including L’Illustration). Guimard may have met him through his wife Adeline, as Webb was part of the small American colony in Paris. After specializing in engraving, he moved to London in the late 1930s, where he died in 1975.

[20] Founded in 1902, ELO had its headquarters and factories in Poissy (Yvelines) and showrooms located at 9 rue Chaptal in Paris’s 10th arrondissement. It offered decorative paneling and fiber cement (a mixture of asbestos and cement) cladding for both interior and exterior use, thanks to its strength, rot resistance, and fire resistance. Manufactured in large quantities, the cladding was designed to imitate wood, bronze, stone, leather, and even ceramic at prices well below those of these materials (Journal Excelsior, May 6, 1925).

[21] The budget allocated to the town hall was 92,000 francs. La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925.

[22] Ferrolithe was a type of coating that imitated stone. Highly resistant and moisture-proof, it was mainly used to renovate and cover exterior walls.

[23] L’Architecture no. 23, December 10, 1925.

[24] Raymond Andrieux was an artist from Lille who became a member of the Société nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1926 in the sculpture category. A trinket tray decorated with a vulture and signed by R. Andrieux was sold at auction in 2016.

[25] Le Grand Écho du Nord de la France, May 21, 1924. BnF/Gallica.

[26] (Jacques) René Ligeron was born in Paris on May 30, 1880, and probably died in Algiers on December 8, 1939. A traveling painter, he was best known for his engravings, with a preference for etchings. A student of Lepeltier, Lefebvre, and Robert-Fleury, he exhibited mainly landscapes and a few portraits at the Salon des Artistes Français from 1905 onwards. In 1936, the press reported on an exhibition in a Parisian gallery showcasing his latest works, notably blackened wooden panels intended to decorate a large dining room, one fragment of which, featuring Japanese-inspired decoration, has recently been rediscovered.

The « Maison Moderne » of Julius Meier-Graefe — Part 3

30 August 2025

The tenuous links between La Maison Moderne and Guimard

Following Bertrand Mothes’ two articles recounting the history and operations of La Maison Moderne, we would like to add some information about the indirect links that existed between this gallery and Hector Guimard, beginning with a few thoughts on how his creations were marketed.

Only a minority of the countless models created by Guimard would have been suitable for sale by an art gallery. Anything that could be considered industrial production, such as cast iron and architectural ceramics or hardware, had to be excluded. However, both furniture and decorative art objects such as vases, lamps, and frames could have been sold through this type of commercial channel. Yet it is easy to see that no art objects designed or modeled by Guimard and then entrusted to a craftsman to be produced as unique pieces or in small series were ever offered for sale at La Maison Moderne or the Bing Art Nouveau Gallery. As Bertrand Mothes showed us in his previous article, at La Maison Moderne, it was usually Julius Meier-Graefe who was responsible for choosing a model presented by an artist and then for its manufacture (and therefore its cost price). However, as at Bing’s, it was possible for certain prestigious brands or artists to deposit their creations in the gallery. The sale of these objects, whose manufacture had already been paid for, therefore generated only a smaller profit shared between the gallery and the designer. However, unlike many artists and decorators, Guimard refused to use the art gallery distribution channel, where his style, which he had wanted to be so distinctive that he gave it his name, would have been anonymized, diluted among multiple expressions of modern decorative art.

He may also have thought that the advantage of having his works permanently displayed in a gallery (which is more effective than occasional exhibitions) could be offset by well-executed media coverage. However, this type of publicity through the press and publications, which had worked very well at the time of Castel Béranger, subsequently became less common and was sometimes even unfavorable to him.

Having chosen to isolate his production from that of others, he could have used a dealer to represent him or even gone so far as to open a store[1]. The first option would again have represented a significant loss of income. As for the cost of running a store, it could have been a deterrent. But above all, Guimard, who was already indeed an entrepreneur, was keen not to appear as a merchant, because of the moral code that architects imposed on themselves, but also because of the business license that would have had to be paid. We know from a lawsuit brought against him, which he won on appeal, that his status as an architect prevailed over that of a merchant. In a dispute with a supplier who claimed that he “combined the practice of his profession with the operation of a veritable industry, that he had manufacturing workshops and stores where he sold various items made under his direction,”. Guimard defended himself by saying that he did not engage in such an activity, but only practiced ”the artistic application and implementation of his knowledge as an architect and his personal taste.”

So Guimard circumvented indirect sales in two ways. First, in a very traditional manner, through direct sales for small production volumes, either by order or at exhibitions. Then, when larger production volumes were expected, he redoubled his efforts not only to have his creations mass-produced but also to have them published. This was not always the case in his early years of artistic creation, and it was only gradually that this approach became widespread, along with the desire to have his designs featured in catalogs. His goal was twofold: to ensure a steady income while working with this wider distribution to promote the “modern style”, and his own style in particular. It should be noted that in most of these catalogs, Guimard’s designs were placed on the same level as the others, just as they would have been on the shelves of an art gallery. And, ultimately, it was the manufacturer who reaped the lion’s share of the profits from the sale. Only in rare cases was he able to obtain the creation of a specific catalog limited to his own designs.

In order to pursue successfully this policy to market his creations, Guimard needed a production unit capable of manufacturing products from start to finish (such as furniture or wooden and plaster frames), or of supplying usable models to a manufacturer, whether a craftsman or an industrialist. He was able to achieve this first Rue Wilhem and then, from 1904 to 1914, Avenue Perrichont prolongée.

Given his great sociability, Guimard did not sever all ties with the art dealers, especially when their commitment to the modern style was sincere and not seen as simply another card to add to an eclectic range of products.

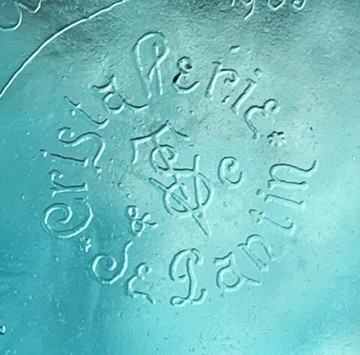

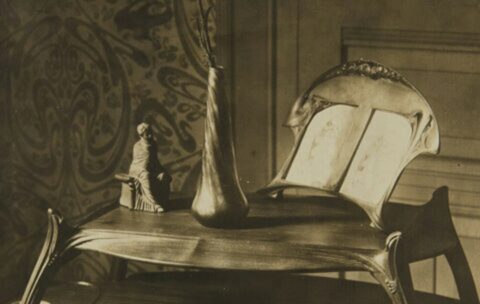

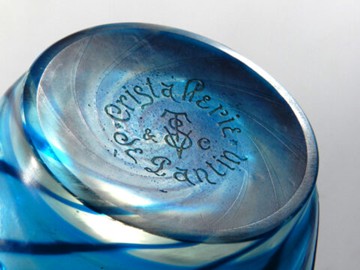

In the article we devoted to the recently acquired Guimard glass vase, we showed that Guimard had collaborated closely with the Cristallerie de Pantin.

Guimard Vase from la Cristallerie de Pantin, height. 40,2 cm. Priv.coll. Photo F. D.

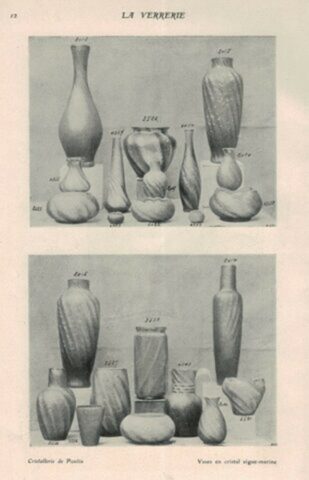

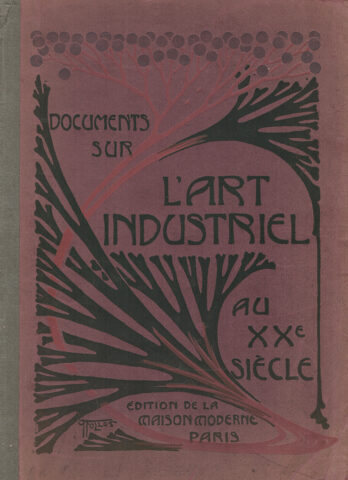

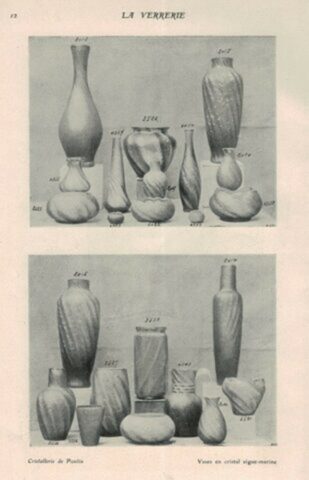

This crystal manufacturer presented a selection of “aquamarine” vases in the gallery of La Maison Moderne, presented in the catalog published in 1901.

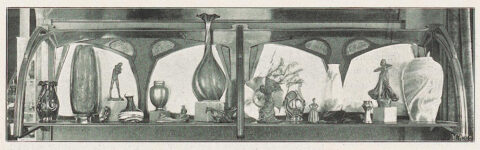

« Crisallerie de Pantin/Aquamarine vases . Documents from L’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (La Maison Moderne catalog), Paris, Éditions de La Maison Moderne, 1901, p. 12.

Aquamarine vase from the Cristallerie de Pantin, close to the vase of 2014 from the sélection of vases sold by La Maison moderne. Photo internet, all rights reserved

For the reasons mentioned above, it is unlikely that any of Guimard’s designs were included in this selection. However, the selection only featured designs with abstract, swirling patterns, far from the naturalistic designs copying the Nancy style that the crystal factory produced in abundance using the same type of slightly bluish glass.

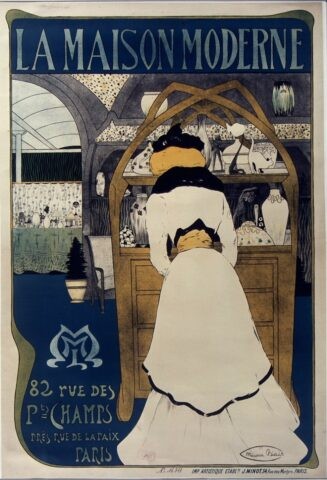

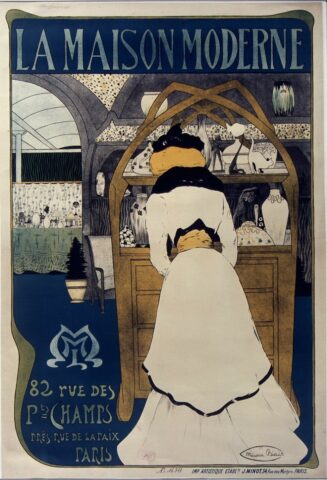

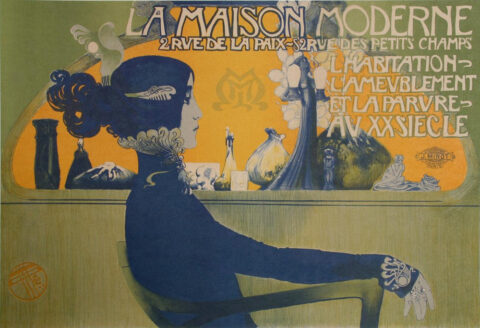

But in the same catalog, the chapter on glassware was written by a friend of Guimard’s, the journalist Georges Bans. In 1895, Bans founded and edited a small bi-monthly literary and artistic magazine, La Critique. Although its circulation was limited, the magazine received contributions from many prominent authors such as Camille Mauclair, as well as excellent illustrators such as Gustave Jossot and Maurice Biais. The latter collaborated with La Maison Moderne, not only with the poster we have already reproduced, but also with drawings of furniture, including an armchair with particularly sober and modern lines.

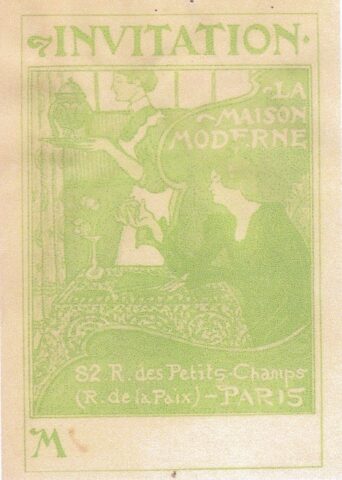

Maurice Biais, imprimerie J. Minot, poster for La Maison Moderne, 1899-1900, color lithography on paper , ighut. 114 m, width. 0,785 m, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Armchair designed Maurice Biais, Musée d’Orsay, mahogany, leather and brasss, hight. 0,86 m, width. 0,70 m, depth. 0,95 m. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay) / Mathieu Rabeau, rights reserved. This armchair is presented in L’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (La Maison Moderne catalog), « Ameublement et décoration », fauteuil renversé n° 35, p. 16, 1901.

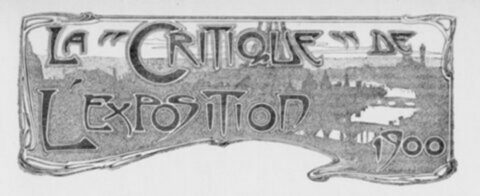

Also noteworthy is the beautiful frontispiece designed for the chronicle of the 1900 World’s Fair in La Critique by Maurice Dufrène, one of the main contributors to La Maison Moderne.

Frontispiece drawn by Maurice Dufrène for the chronicle of 1900 Exposition Universelle in La Critique. Source Gallica.

La Critique was mainly run by Émile Strauss and the poet and critic Alcanter de Brahm (pen name of Marcel Bernhardt). Hector Guimard quickly developed an intellectual rapport and undoubtedly a friendship with the latter, which led to him being frequently quoted in the magazine[3]. Georges Bans also followed Guimard’s career and presented several of his works in La Critique, notably the Paris metro entrances. In a brief note [4] published in August 1900 in La Critique, clearly informed by a disgruntled Guimard, he vigorously contested the battle waged by two city councilors, Charles Fortin and Maurice Quentin-Beauchard, who were fighting to have the kiosks replaced by open surrounds. To restore them, he was appealing to the Prefect of the Seine, Justin de Selves, who was careful not to intervene. A second article by Georges Bans, published two months later in October 1900, this time in L’Art Décoratif, commented very favorably on the installation of the first metro entrances, inventing the famous phrase “the dragonfly spreading its light wings” to describe the inverted roof of the B kiosks. On this occasion, we can guess that Guimard personally explained to him certain details and motivations behind his work that most critics of the time did not perceive.

We can also cite an article by Georges Bans in the German magazine L’Architecture du XXe siècle, which features two drawings of Guimard’s facade elevations and refers to the dinner at La Critique on December 31, 1900, which Guimard attended, as well as the joint participation of Guimard and Bans in the office of the company Le Nouveau Paris, founded in 1903 by Frantz Jourdain.

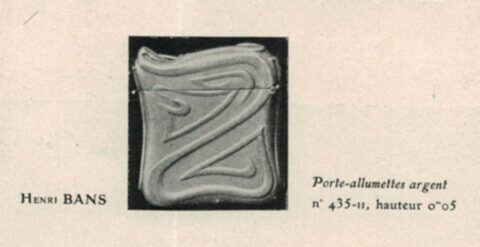

The catalog of La Maison Moderne also features a silver matchbox holder by the young architect Henry Bans[5], brother of Georges Bans.

Henry Bans, matchbox holder, « L’Orfèvrerie », L’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (La Maison Moderne catalog), Paris, Éditions de La Maison Moderne, 1901, p. 11. Coll. part.

Henry Bans was a close friend of the family of sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1829-1875)[6]. Guimard expanded the Carpeaux studio in 1894-1895 on Boulevard Exelmans with the creation of an exhibition gallery dedicated to the sculptor’s work. It was probably on this occasion that he met the Bans brothers.

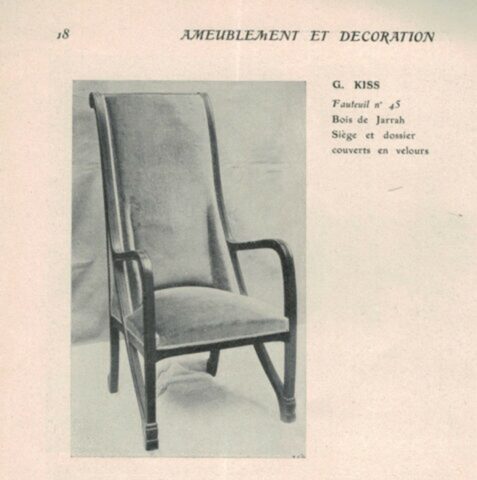

Finally, it is worth noting the presence in the La Maison Moderne catalog of an armchair by Géza Kiss, No. 45 in Jarah wood, which can be seen partially reproduced in Maurice Biais’ poster (see above).

Géza Kiss, armchair n° 45, jarrah wood, seat and back covered in velvet, « Ameublement et décoration », L’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (La Maison Moderne catalog), Paris, Éditions de La Maison Moderne, p. 18, 1901. Private collection

Without going any further (see note 3), we can assure that Kiss, Guimard, the editors of La Critique, and of course Julius Meier Graefe knew each other.

Frédéric Descouturelle

Notes

[1] One immediately thinks that the shop or shops planned for the ground floor of the Castel Béranger, which we do not yet know whether they actually operated, would have been an ideal showcase for Guimard. However, there is no evidence to suggest that he had this intention at any point.[2] Guimard v. Mutel case, ruling of the Seine Commercial Court of January 4, 1901, overturned by the Seine Court of Appeal on January 14, 1904, “Jurisprudence” La Construction Lyonnaise, January 1912.

[3] We will soon review these quotes from Guimard in La Critique.

[4] G. B. “Notule, Le monde à l’envers,” La Critique, August 5, 1900.

[5] François Gabriel Bans, known as Henry or Henri Bans (1877-1970).

[6] Henry Bans would much later design the stele for the Carpeaux monument in Square Carpeaux in Paris’s 18th arrondissement. The monument is adorned with a bust sculpted by Léon Fagel in 1929.

Translation: Alan Bryden

Signing of the long-term lease commitment for the Mezzara Hotel

28 July 2025

On the morning of July 25, the Mezzara Hotel briefly reopened its doors for the signing of the 50-year lease commitment, in the presence of the Minister for Culture Ms. Rachida Dati and numerous other dignitaries.

Welcome for Ms. Dati by Nicolas Horiot, president of the Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

After a brief visit and speeches by Fabien Choné, President of the Fabelsi Holding company, and Ms. Dati, who emphasized the importance of promoting heritage in a dynamic way rather than waiting until it is in danger, highlighting the unusual approach taken jointly by a private entrepreneur and an association of art historians, the official signing took place in the dining room.

Speech by Fabien Choné. Photo D. M.

Signing of the lease commitment Photo D. M.

This morning was an opportunity for the Cercle Guimard and Fabien Choné to reconnect with many of the people who support us and with whom we are developing our museum project. This ceremony was just one step in a process that should continue with a building permit, which will determine when restoration and renovation of the building can actually begin.

The signing of the lease commitment for the Hôtel Mezzara was widely reported in the media, from social networks to icibeyrouth.com and the local press in Saint-Dizier, demonstrating enthusiasm that extends far beyond specialized circles and national borders.

Le Cercle Guimard

The « Maison Moderne » of Julius Meier-Graefe — Part 2

7 July 2025

Organization, offerings, and operation of La Maison Moderne

Among all the artists selected, two Belgian compatriots were given the most important assignment: Georges Lemmen, first and foremost. Meier-Graefe entrusted him with the task of designing the most recognizable element of the brand: its logo. This symbol, intended to be the “brand” of La Maison Moderne, consisted simply of the initial letters of the gallery’s name superimposed on each other, drawn in curves in line with the style already used by Lemmen in the posters for Dekorative Kunst. Simple in design, this logo appeared on most of La Maison Moderne’s production and publications, in its original or a more elaborate form.

Georges Lemmen, logo of La Maison Moderne, 1899.

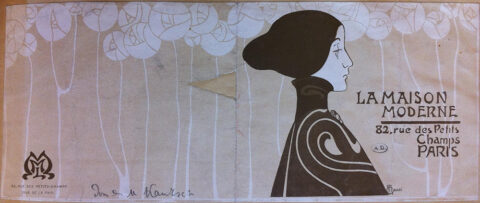

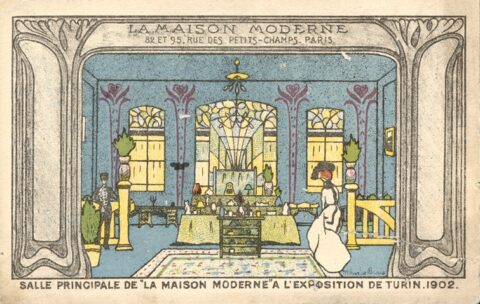

The design of La Maison Moderne was commissioned to the artist Meier-Graefe trusted most: Henry Van de Velde. He designed a storefront with display windows, allowing passersby to see a selection of the items sold inside.

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg. On the shelf of the display cabinet are two vases by Dufrène and Dalpayrat.

Maurice Dufrène, designer, Dalpayrat and Lesbros, ceramist, flamed stoneware, c. 1899, purchased by the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs at La Maison Moderne in 1899, silver mount by Cardeilhac added in 1900, exhibited at the UCAD pavilion at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1900, Musée des Arts Décoratifs. All rights reserved.

The typography for the letters was designed by Georges Lemmen[2]. This choice reflects Meier-Graefe’s confidence in the talent of the two Belgian artists, as the shop front played as important a role as a poster for shops at the end of the 19th century. In the gallery, Van de Velde proposed a complete decor, alternating display cases, shelves, and furnished rooms.

The other artists selected to appear in the gallery catalog were countless: more than sixty were listed. Despite Meier-Graefe’s stated desire to create a gallery that favored French works, foreign artists were very numerous within its walls.

Bernhard Hoetger (Hörde, Germany, 1874 – Beatenberg, Switzerland, 1949), The Storm, c. 1901, bronze, Musée d’Orsay, RF 4189, height 0.311 m, width 0.245 m, depth 0.25 m. All rights reserved. This sculpture is reproduced in Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, bronze 3322-1, La Sculpture p. 5.

To provide an overview of the diversity of the offerings, it is worth mentioning all the nationalities represented among La Maison Moderne’s collaborators: French, Belgian, German, Italian, Austrian, Hungarian, Romanian, Serbian, Danish, Dutch, and Finnish. It is interesting to note the absence of British and Spanish artists among them. Meier-Graefe’s taste is the only real common denominator among all these artists, and they were selected with a concern for consistency that was dear to him (Bing had been criticized for a lack of consistency four years earlier).

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

The establishment also offered a wide range of products: the article announcing its opening in September 1899 stated that “The galleries of the ‘Maison Moderne’ will contain a little bit of everything: furniture, upholstery fabrics, carpets, ceramics, glassware, lighting fixtures, embroidery, lace, jewelry, fans, toiletries, and fancy items—from brushes to cane knobs—in short, everything for the home and the person[3].” This prediction was clearly confirmed: La Maison Moderne offered everything needed to furnish an interior and all the accessories—except clothing—that a wealthy person in the early 20th century might need. The same article also mentions a selection of master painters whose works were offered for sale: Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Auguste Renoir, Maurice Denis, Théo Van Rysselberghe, Édouard Vuillard, and Pierre Bonnard. However, this article remains the only mention of the painting exhibition at La Maison Moderne. We do not know which paintings were exhibited there, and no other artists can be identified.

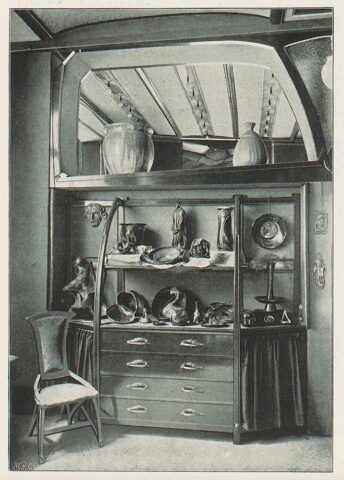

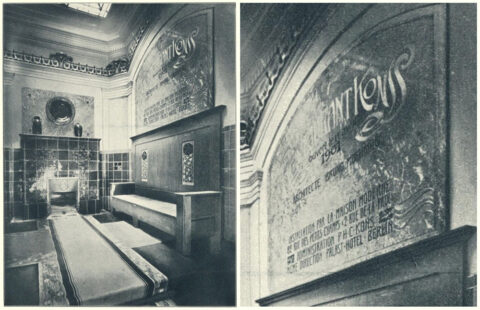

In addition to offering individual items for sale, the gallery also designed and furnished rooms, apartments, and other types of interiors. Most of these complete designs were carried out under the direction of Abel Landry, Pierre Selmershein, or Maurice Dufrène. No examples have survived other than old photographs, such as those of this fashion store, also designed by Van de Velde for the Palast Hotel on Potsdamer Platz in Berlin, managed by P. H. C. Kons.

Henri Van de Velde, interior design of a fashion store “filiale de Madame Henriette” in the Palast Hotel in Berlin, realized by La Maison Moderne with furniture designed by Abel Landry, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

The most important and best documented order was for the interior design of the German restaurant Konss[4], located in Paris on the corner of Rue Grammont and Boulevard des Italiens, on the first floor, also for P. H. C. Kons. The architect appointed by the owner to oversee the work was Bruno Möhring[5]. He decided on the overall layout of the place, and Kons renewed his trust in La Maison Moderne for the design and installation of the decorations. The work took place from January 15 to April 17, 1901. A real success, La Maison Moderne’s participation in the design was noted in the entrance hall of its establishment. A few months later, Meier-Graefe reported on it in L’Art Décoratif, under one of his pseudonyms: G. M. Jacques[6]. Reading this article, it is striking that, having signed it with a French-sounding pseudonym in his French magazine, Meier-Graefe adopts a point of view that could be that of a Parisian journalist, criticizing Möhring’s design by claiming that his “Latin instincts are closed to his Germanic conception.” “when it was in fact his own company that carried out the development. By sticking to what he imagined to be a ”Latin” mindset, he no doubt wanted to avoid any suspicion of a conflict of interest.

Bruno Möhring, landing on the staircase of the Konss restaurant, on the first floor of 30 rue de Grammont in Paris, 1901, executed by La Maison Moderne, ceramics by Laüger, Architektonische Monatshefte, VII. Jahrgang 1901, pl. 88, Leipzig/Vienna, Friedrich Wolfrum, 1901, online library of the University of Stuttgart.

Bruno Möhring, green dining room of the Konss restaurant, first floor of 30 rue de Grammont in Paris, 1901, executed by La Maison Moderne, panels by Georges de Feure, Architektonische Monatshefte, VII. Jahrgang 1901, pl. 87, Leipzig/Vienna, Friedrich Wolfrum, 1901, online library of the University of Stuttgart.

Bruno Möhring, lilac dining room of the Konss restaurant, on the first floor of 30 rue de Grammont in Paris, 1901, executed by La Maison Moderne, L’Art Décoratif, November 1901, article by G. M. Jacques (Julius Meier-Graefe). Online library of the University of Heidelberg.

La Maison Moderne’s operating model is very well thought out, reflecting its director’s careful consideration and innovative abilities. Aware of the behavior of French collectors, who treat art objects in the same way as paintings or sculptures, Meier-Graefe proposed an organization inspired by the Vereinigten Werkstätten für Kunst im Handwerk (United Workshops for Art and Craft) in Munich. While French decorative art remained primarily a commissioned art form, in which artists responded only to specific requests by creating unique models that could not be reproduced, Meier-Graefe proposed the opposite system: objects were no longer commissioned by individuals but were mass-produced by artists and craftsmen. However, production remained in the realm of craftsmanship and did not shift to industry. In the absence of administrative archives from the gallery, no precise figures can be given: the number of pieces produced for the same model must have been relatively small, but there were no unique works. Without even mentioning taste or style, it was first and foremost the way of thinking that the director of La Maison Moderne wanted to change.

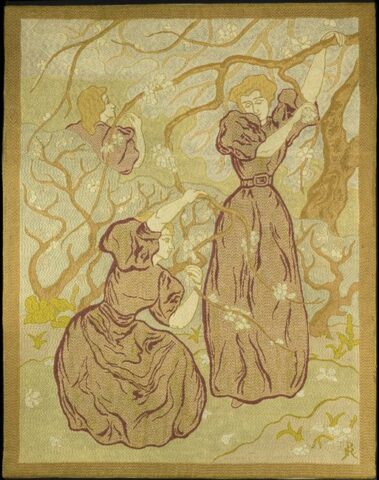

There were exceptions to this system. Tapestries by Paul-Élie Ranson, handmade by his wife France Ranson-Rousseau in single copies, were offered for sale at La Maison Moderne[7].

Paul-Élie Ranson, Printemps (Spring), wool tapestry on canvas executed by France Ranson-Rousseau, 1895, height 1.67 m, width 1.32 m, Musée d’Orsay, OAO 1788, rights reserved.

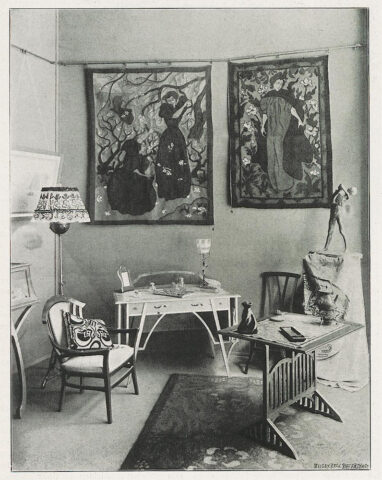

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris. On the wall, two tapestries by Paul-Élie Ranson: Printemps and Femme en rouge, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

Exhibition Femmes chez les nabis. De fil en aiguille (Women among the Nabis. From thread to needle) at the Pont-Aven Museum (June 22 to November 3, 2024), evoking the room in La Maison Moderne where Ranson’s tapestries were displayed. Photo by Bertrand Mothes.

However, these objects were made before the gallery opened and therefore do not fall under the manufacturing method developed by Meier-Graefe. The principle is simple: artists create designs and grant production rights to the gallery, which is responsible for executing them. The artist receives a portion of the sale price—defined by mutual agreement—for each object sold[8]. The possibility of producing multiple copies also allows Meier-Graefe to sell his objects at a “reasonable price,” in his own words. The “reasonable price” encourages purchases and provides the artist with a comfortable income. Here, “reasonable” should not be confused with “low.” While the prices of the objects sold at La Maison moderne did not reach those seen at Bing, they were nonetheless accessible to fairly well-off individuals, rather than workers or low-paid employees.

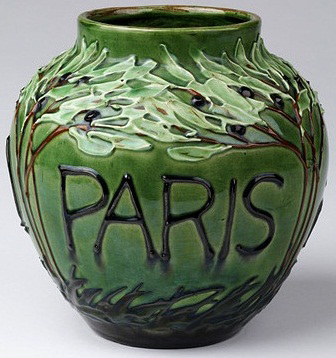

The gallery had its own workshops for the production of objects. The only one that can be confirmed with certainty is the leather workshop[9], but it is possible that there were also workshops for cabinetmaking, tapestry, brasswork, jewelry, and watchmaking. The fire arts, which were difficult to set up on a large scale in the heart of the Parisian capital, came from manufacturers associated with La Maison Moderne. The vase Exposition 1900 Paris, from Germany, is a good example. Manufactured by Tonwerke in Kandern, run by Max Laüger, it is not part of the factory’s usual production but was made exclusively for LMM, as evidenced by the gallery mark incised under its base alongside Laüger’s monogram and the factory mark.

Max Laüger, Tonwerke workshop, Vase Exhibition 1900 Paris, circa 1900, painted earthenware under glaze, produced by La Maison Moderne, height 0.212 m, London, Victoria & Albert Museum. All rights reserved.

Max Laüger, Tonwerke workshop, Vase Exhibition 1900 Paris, circa 1900, painted earthenware under glaze, height 0.212 m, Paris, Musée d’Orsay. All rights reserved.