Month: January 2026

Guimard, brick by brick

Throughout his career as an architect, Guimard paid close attention to the variety of bricks available on the market. In this article, we provide an overview of their use, which may be expanded based on more comprehensive studies of the building materials he used in his buildings.

Very roughly speaking, it should be noted that North of the Loire, in regions rich in limestone, fired clay bricks were rarely used until the Renaissance, when, in imitation of Italian buildings, they became a sought-after material, despite their production cost, and were even used in the construction of castles in the 16th and 17th centuries. Its production cost fell between the 18th and 19th centuries because of its gradual industrialization. From then on, its increasing use in economical construction led to a decline in its value as a material and its relegation to the status of a poor material. It was against this trend that, from the second half of the 19th century onwards, brick gradually regained its prestige thanks to more sophisticated production. A variety of tones was obtained by composing pastes with varying amounts of iron oxide, or by coloring or glazing its faces. This expansion of the product range naturally accompanied the movement in favor of polychrome urban facades initiated by Jacques-Ignace Hittorff (1792-1867) and later by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879).

Terracotta brick

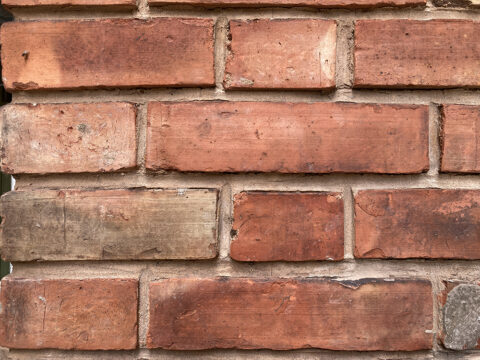

Influenced by Viollet-le-Duc and concerned with both originality and economy, Guimard made extensive use of brick in his early villas, built before Castel Béranger in the 16th arrondissement and in the western suburbs of Paris. He mainly used pink-orange and red bricks, sometimes punctuated with glazed bricks.

Hôtel Roszé, 1891, 34 rue Boileau, Paris XVIe, Photo F. D.

Hôtel Jassedé, 1891, 41 rue Chardon-Lagache, Paris XVIe, Photo F. D.

They alternate with millstone and cut stone, which is rarer and chosen for certain key elements of the facades: capitals, lintels, cornices, etc. The result is a mixture of colors which, combined with the particularly colorful ceramics, reinforces the picturesque appearance of these residences.

The more aristocratic-looking Hôtel Delfau stands out with its almost monochrome façade, which mainly uses straw-yellow brick that blends in with the cut stone used for the front section and its large dormer window. Guimard deliberately limited the use of red brick to simple courses that highlight the cornices, just as he restricted the color of the architectural ceramics to blue alone.

Hôtel Delfau, 1894, 1 ter rue Molitor, Paris XVIe, Photo F. D.

The advent of Art Nouveau in 1895 did little to change this choice of materials. An economical building such as the École du Sacré-Cœur simply used less stonework that was less sculpted than on the Castel Béranger. For the Castel Henriette, rubble stone in opus incertum replaced millstone.

École du Sacré-Cœur, 1895, 9 avenue de la Frillière, Paris XVIe, Photo F. D.

Upper floors of the street facade of the Castel Béranger, 1895–1898, 14 rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine, Paris XVIe. Photo F. D.

Detail of the courtyard façade of the Castel Béranger, 1895–1898, 14 rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine, Paris XVIe. Photo F.

Generally, bricks have the brickworks’ mark embossed on one of their long, narrow sides. So far, we have only found the “CB” logo on the bricks of the Hôtel Roszé and that of the Chambly brickworks (in the Oise region) on those of the Castel Val. It is possible that in most cases, Guimard instructed the contractor to hide the marks by exposing the opposite long side.

Detail of the street facade of the Hôtel Roszé, 1891, 34 rue Boileau, Paris XVIe. Photo F. D.

Detail pf the façade of Castel Val, Auvers-sur-Oise (Val d’Oise), 1902-1903. Photo F. D.

For the Humbert de Romans concert hall (1898-1901), thanks to the attachment plan preserved in the Guimard collection at the Musée d’Orsay, we know precisely the types of bricks used for the masonry. A top-quality Sannois brick (white) was used for the main facade and the patronage. It was doubled with a Belleville brick, also top quality.

For the Castel Béranger, on smaller areas of the street facade and in the courtyard, Guimard also used glazed terracotta bricks, with a color that gradually changed from light blue to beige.

Detail of the courtyard façade of the Castel Béranger, 1895–1898, 14 rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine, Paris XVIe, Photo F.

It is likely that they came from the Gilardoni & Brault tile factory, as this company is mentioned in the list of suppliers for Castel Béranger. The company also supplied the artistic glazed ceramics used on the façade and some of the chimney narrowings in the apartments.

Hector Guimard, L’Art dans l’Habitation moderne/Le Castel Béranger (portfolio of Castel Béranger), list of suppliers (detail), Librairie Rouam, 1898. Private collection.

It is noteworthy that in all cases where bricks of different colors were used, Guimard never created alternating color patterns as seen on many buildings of that period, because these designs, which would necessarily be geometric, would have competed with his own decorations. To create curved patterns, large flat surfaces would have been required, and the result would not necessarily have been satisfactory. At most, he contented himself with beds of different colors to highlight cornices or simulate a bed frame.

Detail of the façade on Rue Lancret of the Jassedé building (1903–1905), Paris XVIth arrondissement. Photo F. D.

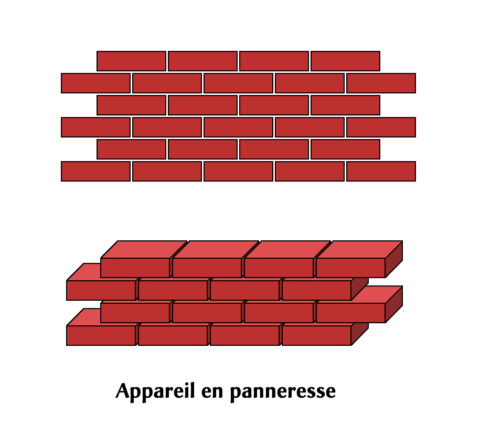

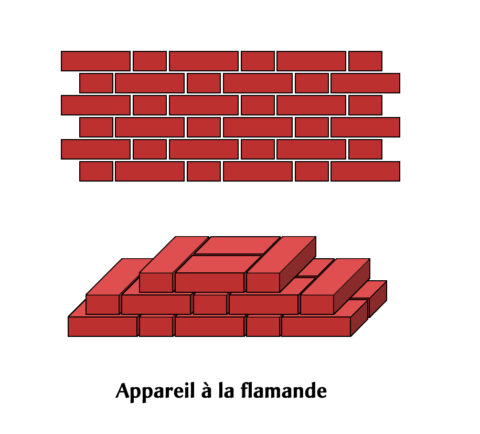

Few types of masonry are used. These are mainly stretcher bond and Flemish bond[1], which alternate headers (the smaller side) and stretchers on each course.

.

.

Panneresse and Flemish devices. Drawings by F. D.

The small size of the brick makes it easy to curve a wall. However, Guimard did not immediately exploit this possibility and stuck to flat walls in his early buildings. Even when he curved the central span of the Villa Berthe in Le Vésinet (1895) or the oriel window of La Bluette in Hermanville (1899), he used cut stone, which was more expensive to work with. He probably preferred the softer surface of the stone, which better complemented the movement he was creating.

Main façade of the Villa Berthe, Le Vésinet (Yvelines), 1896. Photo Nicolas Horiot

It was not until the Castel Henriette (1899) that curved brick sections appeared. For the first time, its design gave prominence to curved elevations, but these were mainly constructed using opus incertum rubble stone. A few years later, Castel Val in Auvers-sur-Oise (1902-1903) was the finest example of curved facades using brick, a technique that Guimard repeated shortly afterwards in a more discreet manner on the Jassedé building, at the corner of Avenue de Versailles and Rue Lancret (1903-1905) .

Facade of the first floor of Castel Val, Auvers-sur-Oise (Val d’Oise), 1902-1903. Photo Nicolas Horiot.

Street facade of the Jassedé building at the corner of Avenue de Versailles and Rue Lancret, Paris XVIth arrondissement, 1903-1905. Photo F. D.

Sand-lime brick

Around 1904, Guimard began using sand-lime brick. This material is not obtained by firing natural or reconstituted clay: it is an artificial stone similar to cement.

Sand-lime bricks laid in Flemish bond on the street façade of the Hôtel Mezzara, 60 rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine, Paris XVIth arrondissement, Photo F. D.

Even if the principle behind it is much older, it was not manufactured industrially until the late 19th century[2]. Composed of 90% silica sand, quicklime (calcined limestone), and water, the mixture is molded into bricks that are compressed and then hardened in a steam boiler. On close inspection, you can see the coarse sand and gravel that make up the mixture. As a result, while terracotta bricks are virtually unalterable, after a century these bricks show signs of wear, with the grains gradually coming loose.

Sand-lime bricks on a chimney stack at the Hôtel Mezzara, 60 rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine, Paris XVIe. Photo Nicolas Horiot.

On the other hand, its high density makes it heavy, and its thermal inertia is poor. However, this material also has many qualities, including low cost due to low energy consumption during production, compressive strength that allows it to be used in load-bearing walls, fire resistance, and good acoustic quality.

Guimard’s use of this material coincided with a stylistic shift away from the somewhat garish polychromy of his early work toward a more discreet elegance. The gray-beige color of sand-lime brick blends in well with that of cut stone.

As he had done earlier with terracotta brick, Guimard first experimented with this new material alongside rubble stone for villas and suburban houses such as the Castel d’Orgeval in Villemoisson-sur-Orge (1904), where it highlights the windows and individualizes remarkable surfaces. In contrast, it appears very discreetly on the villa in Eaubonne (c. 1907), then a little later on the Châlet Blanc in Sceau (1909), and finally in a more prominent way on the Villa Hemsy in Saint-Cloud (1913).

Window on the ground floor of the street-facing façade of the villa at 16 rue Jean Doyen in Eaubonne (Val d’Oise), c. 1907. Photo F. D.

But it is in his urban constructions, starting with the Hôtel Deron-Levent (1905-1907), that sand-lime brick seems to be most appropriate. Next came the Trémois building on Rue François Millet (1909-1911), the “modern” buildings on Rue Gros, La Fontaine and Agar streets, his mansion on Avenue Mozart (1909-1912) and the Hôtel Mezzara on Rue La Fontaine (1909-1911), where sand-lime brick is used in conjunction with cut stone, the surface of which varies according to the desired luxury effect.

Street facade of the Mezzara Hotel, 60 rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine, Paris XVIth arrondissement, rubble stone base, sand-lime brick facing, window sills and frames in cut stone. Photo F. D.

Guimard also used different brickwork patterns with sand-lime brick. The Hôtel Guimard at 122 Avenue Mozart (1909), with its particularly dynamic façade, is a good example of how these techniques were used to reduce the thickness of the walls and lighten the masonry towards the top, adapt to the folds in the façades, and reinforce certain walls at specific points.

Detail of the second and third floors of the façade of the Hôtel Guimard. Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs, donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

The main body of its walls is constructed using Flemish bond, resulting in walls 45 cm or 22 cm thick. To create the curves and begin the folding of the facade, header bond was used, sometimes supplemented by alternating multiple header bond to reinforce the strength of the walls, particularly around certain openings. In the upper parts, the use of a regular header bond technique made it possible to lighten the masonry of the top floor at the loggia level, resulting in walls only 11 cm thick.

Detail of the second and third floors of the facade of the Hôtel Guimard. Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs, donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

It was also from 1909 onwards (Hôtel Guimard, courtyard of the Trémois building, Hôtel Mezzara) that a model of bricks with rounded corners began to appear, particularly at the jambs of the windows, where they softened the transition from one plane to another.

Detail of the left bay on the first floor of the street façade of the Hôtel Mezzara, 60 rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine, Paris XVIe. Photo F. D.

After the war, sand-lime brick was still used on the Franck building on Rue de Bretagne (1914-1919). A little later, it gave way to yellow terracotta brick for the luxurious building on Rue Henri-Heine (1926), where Guimard used it only on the top floors, where it is less visible.

Yellow terracotta brick and sand-lime brick on the fifth floor of the street facade of the Guimard building at 18 rue Henri-Heine, Paris XVIe, 1926. Photo F. D.

But it made a strong comeback with affordable buildings such as the Houyvet building, Villa Flore (1926-1927), and the buildings on Rue Greuze (1927-1928), and undoubtedly with his villa La Guimardière in Vaucresson (1930).

Rear facades and overlooking Villa Flore of the Houyvet building, Paris XVIth arrondissement, 1926-1927. Photo F. D.

Parapet and window on the fifth floor of the façade overlooking Villa Flore on the Houyvet building, Paris 16th arrondissement, 1926–1927. Photo F. D.

Detail of the street facade of the first floor of 38 Rue Greuze, Paris XVIe, 1927-1928. Photo F. D.

As can be seen in the previous photos, after World War I Guimard introduced effects of volume and therefore light by placing certain bricks in a different way in relation to the surface, for example protruding, recessed, or slanted. These techniques have been well known for centuries and are used to emphasize vertical or horizontal lines, or to punctuate a flat surface. However, just as he refused to use repetitive patterns of alternating brick colors, he also did not take advantage of the possibility of playing with the relief of brick walls during the first part of his career, rightly considering that their surface should remain neutral and not compete with his own decorative motifs (carved in stone or modeled in ceramic), which he reserved for limited locations. However, caught up in the general stylistic evolution that initially advocated the geometrization of decoration before its gradual abandonment, Guimard decided to introduce these surface effects as he abandoned his personal decorative motifs. He was certainly not the only one to use this motif of bricks placed at a 45° angle, with the angle flush with the surface (below).

Detail of the street facade of the second floor of the Guimard building at 18 rue Henri-Heine, Paris XVIe, 1926. Photo F. D.

But perhaps he is the inventor of this original pattern, in which one brick is rotated 30° and the next is symmetrical to it. On the course above, the same sequence is offset by one course width.

Lintel of a window on the fifth floor of 36 Rue Greuze, Paris XVIe, 1927–1928. Photo F. D.

Asbestos brick

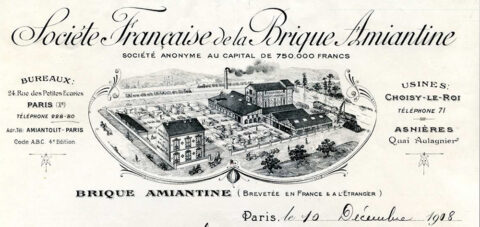

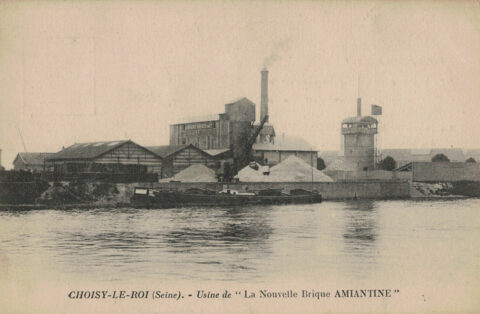

Also known as asbestolite, asbestos brick was manufactured in France in Choisy-le-Roy from 1904 onwards by the Société française de la brique amiantine using asbestos fiber imported from Canada.

Letterhead of the Société Françaises de la Brique Amiantine, letter dated December 10, 1908, photograph taken from Pierre Coftier’s article, “La brique amiantine de Choisy-le-Roy” (Asbestos brick from Choisy-le-Roy), L’actualité du Patrimoine, no. 8, Dec. 2010. All rights reserved.

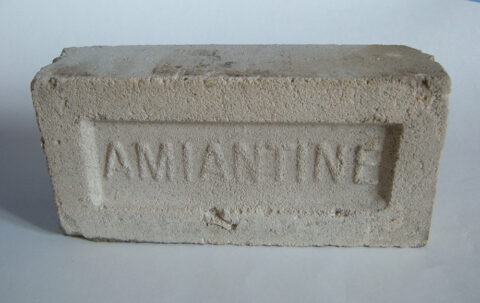

The addition of this mineral[3] was intended to increase the (already good) fire resistance of sand-lime bricks, improve their low insulating properties, and even provide an antifungal effect. The product, which could be colored, was seen as innovative compared to simple sand-lime bricks and was therefore highly valued. To clearly differentiate them, the “Amiantine” brand name was embossed in a recess on one of the two large faces of the bricks.

Large side of an asbestos brick. Photograph taken from Pierre Coftier’s article, “La brique amiantine de Choisy-le-Roy” (The asbestos brick of Choisy-le-Roy), L’actualité du Patrimoine, no. 8, Dec. 2010. All rights reserved.

The Choisy-le-Roy site was acquired in 1922 by Lambert frères & Cie.

Lambert Frère & Cie factory in Choisy-le-Roy, old postcard. Private collection.

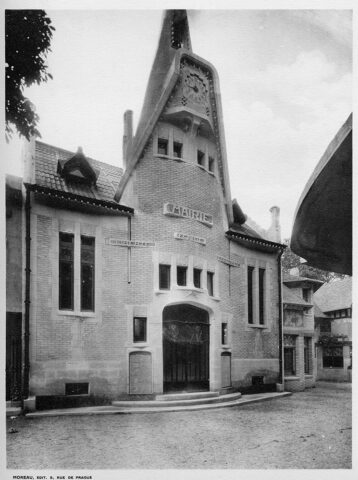

Guimard appears to have used these products for the first time in 1925 at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts for his participation in the French Village[4] as part of the Modern Architects group, of which he was vice-president.

As the designer of the village town hall, he used asbestos brick[5] more extensively on the main façade than on the rear façade. This brick is mentioned, along with the Lambert cement factory, in groups of three stretching courses, clearly visible in four locations: two on the main façade and two on the rear façade. The Maison du Tisserand[6] by architect Émile Brunet, adjoining the town hall on the right, and undoubtedly other buildings in the village also used this material. The tiles on the town hall were made of weathered fiber cement and were also supplied by the Lambert cement factory[7]. This touches on one aspect of the French Village which, like other similar events, was only able to balance its budget by supplying materials at preferential rates in exchange for discreet but effective advertising.

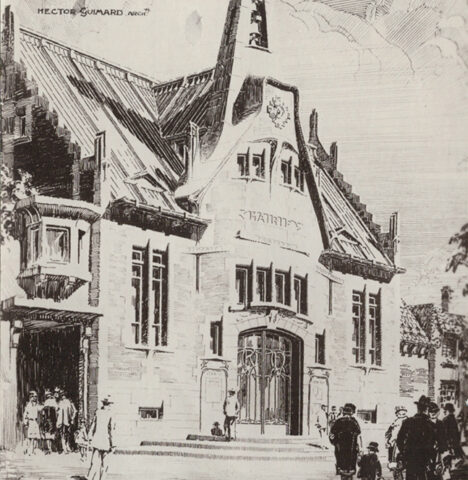

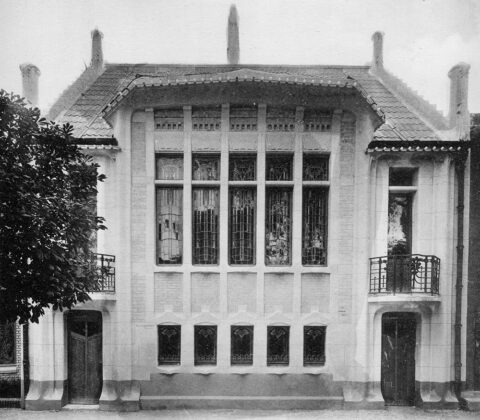

Main façade of the French Village town hall at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim, Charles Moreau, 1926, pl. 2. Private collection

Rear facade of the French Village town hall at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts (detail), 1925, portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim, Charles Moreau, 1926, pl. 3. Private collection.

As proof of Guimard’s constant interest in new building materials and their evolution, he exhibited in the large hall on the ground floor of the town hall “some of the materials used in its construction[8].” These included, for example, two types of brick whose exact use in the town hall is unknown: “the double 6 x 2222 brick, hollow, easy to use,”[9] whose manufacturer is unknown, and bricks produced by the “Société de Traitement des Résidus Urbains” (Urban Waste Treatment Company) run by a certain Grangé. In an article devoted to new products at the 1925 Exhibition, the magazine L’Architecture shed some light on their manufacturing process:

“[…] The bricks and cinder blocks of the Société de Traitement Industriel des Résidus Urbains, manufactured using silico-calcareous processes with clinkers (slag) from the incineration of household waste in the city of Paris, obtained by melting and vitrification at high temperature (1,200°C) of the non-combustible products contained in household waste. [10] “

To encourage players in the construction industry to discover its products, Grangé used an advertising card with a drawing of the French Village town hall by Alonzo C. Webb (1888-1975)[11] on the back, which also appeared in La Construction Moderne.

A.C. Webb, drawing of the main façade of the French Village Town Hall, card issued by the Urban Waste Treatment Company inviting people to visit the French Village Town Hall exhibition hall, front. Private collection.

Card issued by the Urban Waste Treatment Company inviting visitors to visit the exhibition hall at the French Village town hall, reverse side. Private collection.

Another supplier of materials to Guimard, a quarry operator in Thorigny-sur-Marne and manufacturer of special plasters, was also known to us. The magazine L’Architecture also mentioned his products on display in the main hall of the town hall:

“[…] Notably Taté products, ready-made for coatings and renovations imitating stone, classified into three categories and whose names, bearing only a tenuous relationship to the designations indicated in parentheses, are as follows: lithogène (slow setting), pétra stuc (fast setting), alabastrine (alabaster alum plaster).”

We are certain that “petra-stuc” was used in the construction of the town hall, as we can make out the name written on the base above the basement window[12]. We can also read the name Taté on the photograph.

Main façade of the French Village town hall at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts (detail), 1925, portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim, Charles Moreau, 1926, pl. 2. Private collection.

This fairly dark-colored “petra-stucco” used for the base is more visible in the photograph of the rear facade of the town hall.

Rear facade of the French Village town hall at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, 1925, portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim, Charles Moreau, 1926, pl. 3. Private collection.

The use of this product would be anecdotal if Taté had not harbored a deep resentment toward Guimard, undoubtedly over a financial matter. But instead of settling this dispute through the courts, either civil or commercial, upon learning that the General Commission for the Decorative Arts Exhibition had proposed Guimard for the Cross of Knight of the Legion of Honor, Taté sent a letter of denunciation[13] to the Order’s chancellery, which had the effect of delaying his appointment for four years.

After the 1925 exhibition, Guimard once again used products containing asbestos. Like his colleague Henri Sauvage, he used fiber cement tubes produced by the Éternit company. These can be found in particular on the two buildings on Rue Greuze, where they serve an essentially decorative function, their volume emphasizing the verticality of the bow windows and bays. The plans show that they are half-cylinders.

Building 38 rue Greuze, Paris XVIe. Photo F. D.

These fiber-cement tubes appear to have a more structural function on the terraces of the 6th and 7th floors, similar to their use two years later by Sauvage, who experimented with using them for load-bearing walls in individual homes built with prefabricated elements.

Terrace on the 7th floor of the building at 38 Rue Greuze, Paris, 16th arrondissement. Photo: F. D.

Finally, they are also present at La Guimardière, the villa that Guimard built for himself in 1930 in Vaucresson, using disparate materials that undoubtedly came from his past projects. Unsurprisingly, brick is still very much present in this final construction.

Villa La Guimardière in Vaucresson (Yvelines), Decorative Arts Library, donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Frédéric Descouturelle

Thanks to Nicolas Horiot for the details provided about the Humbert de Romans hall and the Guimard hotel.

Notes

[1] There are variations in the literature regarding the names of the different types of equipment, which can lead to confusion, particularly between English and Flemish equipment.

[2] Granger, Albert, Pierre et Matériaux artificiels de construction, Octave Douin éditeur, Paris, n.d.

[3] The first deaths due to pulmonary fibrosis caused by asbestos were recorded around 1900, but it was not until 30 years later that cases of mesothelioma (cancer of the pleura) were attributed to it. The link was not formally established until the 1950s, but the harmful effects of asbestos were then denied for a long time by the entire production industry and by many politicians, resulting in pollution that is now extremely costly to eradicate.

[4] The French Village was one of the most popular sites in the exhibition, although it was not the best understood by critics and subsequently the most studied by art historians. Rationalist and modern without being revolutionary, rural without being regionalist, it presented, gathered together in a fictional village, different houses, shops, and services, treated in a modern style favoring new materials but without neglecting traditional materials. See Lefranc-Cervo, Léna, Le Village français: une proposition rationaliste du Groupe des Architectes Modernes pour l’Exposition Internationale des arts décoratifs de 1925, Research thesis (2nd year of 2nd cycle) supervised by Ms. Alice Thomine Berrada, École du Louvre, September 2016.

[5] Goissaud, Antony, “La Mairie du Village,” La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925.

[6] Goissaud, Antony, “La Maison du Tisserand,” La Construction Moderne, October 11, 1925.

[7] “Among the exhibitors [inside the main hall], the Lambert Frères company naturally stands out, having supplied the asbestos bricks and tiles for the houses in the Village […]”. Goissaud, Antony, “La Mairie du Village,” La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925.

[8] “New products at the 1925 Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts,” L’Architecture no. 23, December 10, 1925.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid. These combustion residues are commonly referred to as clinker.

[11] See the note on this subject in the article on Guimard’s participation in the 1925 Exhibition.

[12] The editor of La Construction Moderne confused it with a “strongly tinted gray stone,” Goissaud, Antony, “La Mairie du Village” La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925.

[13] We reserve the reproduction of this letter for a future article recounting the twists and turns of this affair.

Translation: Alan Bryden

Hector Guimard’s first trip to the United States – New York 1912

February 2023

While the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York[1] inaugurated an exhibition dedicated to Hector Guimard[2] at the end 2022, which will then moved to Chicago, we are publishing the first in a series of articles on the direct and indirect links between the architect and the United States. In this first article, we thought it appropriate to recount Guimard’s first contact with the United States in the spring of 1912.

Following the death of his father-in-law, American banker Edward Oppenheim, on November 23, 1911, in New York[3], Guimard traveled there in mid-March 1912 with his wife Adeline for a stay of about two months. It was therefore both a private trip and, as we shall see, a business trip. Guimard acted as vice-president of the Society of Decorative Artists, a role he did not hold anymore since several months[4]. It is true that presenting himself under this label gave him the legitimacy to raise certain subjects, even if it meant bending the truth slightly.

The story of this trip began very early on, as an article reported Guimard’s presence on the ocean liner taking him across the Atlantic. Although this first text may seem anecdotal, it reflects the architect’s state of mind as he embarked on his first trip to America. That is why we are offering the best passages from it.

The American press then reported several times on the professional meetings Hector had during this first stay. As the texts are sometimes redundant, we will not provide translations of all of them, but only the French version of the three accounts published in The New York Times on April 5, 1912, The Calumet on April 23, 1912—in which only the extracts directly related to Guimard are included—and The American Architect in May 1912. Finally, we will simply list the other newspapers that reported on the event.

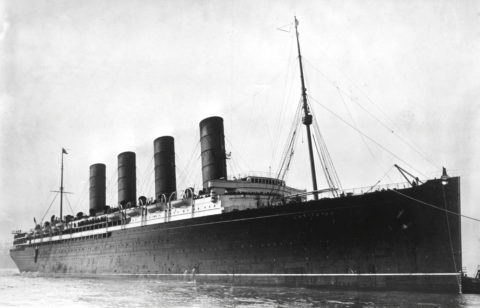

It should be noted that Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard is not mentioned in any of these articles. However, we assume that she was present during the interviews, as Guimard could not speak English[5]. Furthermore, thanks to a postcard sent in 1912 by Guimard to the staff of his offices on Avenue Mozart[6], we know that Hector traveled on one of the two transatlantic flagships of the English company Cunard, but without specifying whether it was the Mauretania or the Lusitania that welcomed him on board. The records of the Ellis Island Foundation and the newspaper article we are about to discuss tell us that it was the latter[7]: the Guimards boarded the Lusitania in Liverpool on March 9, 1912, bound for New York, which they reached on March 15, 1912.

The Cunard liner Lusitania. Source: Wikipedia

Aboard the ship, a chance encounter between a famous English illustrator and caricaturist, Harry Furniss (1854-1925, the author of the text), and his neighbor in the lounge, who was none other than “(…) the distinguished French architect, Mr. Hector Guimard (…)“, is the first known account of the architect’s trip to the United States[8]. Furniss specifies that this was Guimard’s first trip to America, the purpose of which was to study ”skyscrapers and other eccentricities of American architects.” Then, in a rather unfriendly tone, he indicates that Guimard “does not seem to like steel and brick skyscrapers,” even daring to ask the controversial question: “(…) he [Guimard] asks pathetically: why shouldn’t America have its own distinct architecture?” We will see that this reflection, which is one of Guimard’s major concerns about the ability of a country or city to develop a specific and harmonious architecture, will often come up again—albeit in a more diplomatic manner—during his subsequent speeches in New York.

Guimard sketched by Furniss aboard Lusitania. Coll. part.

No hard feelings, but undoubtedly inspired by this encounter, Furniss sketches Guimard, gently mocking the seasickness that seems to affect the architect: “(…) Guimard does not seem to like skyscrapers of steel and brick on land any more than he likes the skyscrapers of seawater that we encountered in the Atlantic (…)”.

Marie-Claude Paris then presents three articles on Guimard that appeared in the American press in chronological order, starting with The New York Times, followed by The Calumet, and finally The American Architect, before providing the original texts in English.

- GUIMARD’S COMMENTS IN AMERICAN NEWSPAPERS

I.1. The New York Times, April 5, 1912

In an article published in the New York Times under the headline “Artists Recall Their Stay at the Jullian Academy “[9], an anonymous journalist recounts a long and joyful commemorative gathering held at the Brevoort Hotel in South Manhattan on April 4, 1912[10]. The article mentions various artists who spent time in France and then became famous or held prominent positions in the art world or museums after returning to the United States.

Brevoort Hotel, Fifth Avenue and 8th Street, New York, New York, 1919. (Photo by William J. Roege/The New York Historical Society/Getty Images.

” Amidst this joyful and noisy crowd, the author notes a single solitary guest of honor, architect Hector Guimard, who, among other things, designed all the entrances to the Paris metro stations. In a brief speech, Hector mentions “the old-timers” and, in passing, America and Americans. “It goes straight to my heart to see old friends, all former students of Jullian, doing so well in your city. It is refreshing to see you show such interest in your student years in Paris. I have been charmed by this magnificent country and I will make only one comment that is not entirely complimentary: Americans are generally too modest.” This was the only speech of the evening, and after the guests were seated, the signal was given to begin the festivities.

I.2 The Calumet, Tuesday, April 23, 1912

In this article, Hector speaks in two capacities: as an architect and as vice president of the Society of Decorative Artists. His view becomes quite critical once again.

“Our architecture would be better appreciated if it had an American character and was not copied. I wondered if it is possible that the tall buildings you have here are pleasing to the eye and practical for housing their many occupants. I believe it is possible, but in my opinion, many examples of your skyscrapers are disappointing in that the idea of harmony[11] in a building has not been followed by the architect.

American architects should exchange ideas so that there is continuity and harmony in the succession of buildings they erect. Your architects show more strength and understand their work more deeply, I believe, than those in Germany or Great Britain, but my impression of New York is more that of a collection of buildings than of harmonious groupings as in Berlin or London.

Some American architects I have spoken to say that they have little latitude, that they have to build as the owner demands.

WHY DOES AMERICA NOT HAVE A SPECIFIC ARCHITECTURE? THERE IS A HUGE OPPORTUNITY. THERE IS NOTHING TO GAIN FROM COPYING OLD METHODS AND OLD MODELS. A DISTINCTIVE, TOTALLY NEW, SIMPLE STYLE, WITHOUT HARD LINES BUT YET STRONG FEATURES COULD EMERGE, ONE THAT WOULD BE RECOGNIZED AS AMERICAN.

Every European country is making this effort to EXPRESS ITSELF IN ITS OWN WAY IN ARCHITECTURE[13]. Germany has made an enormous effort in this direction, and this appears to visitors to Berlin to be largely successful.”

I.3 The American Architect, May 1912

Published at the end of his stay in New York, this last text appears to be a kind of conclusion: Guimard’s opinion on American architecture remains quite clear-cut, even though he takes care to nuance his remarks by citing specific examples of buildings. We also learn that his visit had another purpose: to interest his American counterparts in the future exhibition of modern art being prepared in Paris[14].

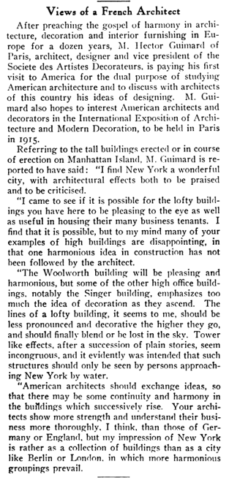

“After preaching the gospel of harmony in architecture, decoration, and interior design in Europe for twelve years, Mr. Hector Guimard of Paris, architect, designer, and vice president of the Society of Decorative Artists, is making his first visit to America with the dual purpose of studying American architecture and discussing his ideas on design with American architects. Mr. Guimard also hoped to interest architects and decorators in the International Exhibition of Modern Architecture and Decoration, to be held in Paris in 1915.

Regarding the tall buildings already erected or planned for Manhattan, Mr. Guimard reportedly said: “I find New York to be a magnificent city, with architectural effects that are both praiseworthy and worthy of criticism. I came to see if it is possible for the tall buildings you have here to be pleasing to the eye and also useful for housing their many tenants. It seems possible to me, but in my opinion many of your tall buildings are disappointing, in that the architect has not followed the idea of harmony in construction.

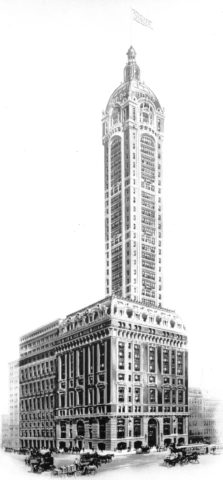

“The Woolworth building[15] will be pleasant and harmonious, but others, such as the Singer building[16] in particular, place too much emphasis on decoration in their upper sections. In my opinion, the lines of a tall building should be less pronounced and less decorative as they rise, eventually blending into or disappearing into the sky. After a series of unstylish floors, “tower” effects seem incongruous, and it is obvious that such structures should only be seen by those approaching New York by sea.

The Woolworth building c.1913. Source Wikimedia Commons.

The Singer building c.1910. Source Wikipédia.

American architects should exchange ideas so that there is continuity and harmony in the buildings that are being constructed one after the other. American architects show more strength and understand their work more deeply, I believe, than their German or English colleagues, but my impression of New York is more that of a collection of buildings than of cities such as Berlin or London, where more harmonious groupings dominate.”

- ORIGINAL TEXTS BY GUIMARD IN THE AMERICAN PRESS

II.1 Original text of part of the article in the New York Times “Artists hark back to days at Julian’s”

“There was one lone guest of honor. He was Hector Guimard, the distinguished French architect, who among other things designed all the subway stations in Paris. He is in America on business, and in a brief speech made some happy comments about the ‘anciens’ and incidentally, American and Americans.

“It delights my heart,” he said, “to find you old fellows, all of whom are Julian’s ‘anciens’, doing so well in this your great home city. It is refreshing to find you taking such an interest in the old student days in Paris. I have been charmed with this magnificent country, and I can make but one comment that could possibly be construed as not entirely complimentary, and that is that Americans as a rule are entirely too modest.“

II.2 Original text from Calumet

”Our architecture would show off better if it had an American distinctiveness and was not copied. By HECTOR GUIMARD of Paris. Vice President of the Society des Artistes Décorateurs.

I have wondered if it is possible for the lofty buildings you have here to be pleasing to the eye as well as useful in housing their many business tenants. I think that it is possible, but to my mind many of your examples of high buildings are DISAPPOINTING in that one HAS one HARMONIOUS idea in construction has not been followed by the architect.

American architects should exchange ideas so that there may be some continuity and harmony in the buildings which successively rise.

Your architects show MORE STRENGTH and understand their business more thoroughly, I think, than that of Germany or England, but my impression of New York is rather as a collection of buildings than as a city like Berlin or London, in which more harmonious groupings prevail.

Some American architects with whom I have talked say they have little latitude, that they must build as the owner directs.

WHY SHOULD AMERICA NOT HAVE A DISTINCTIVE ARCHITECTURE? THERE IS A GRAND OPPORTUNITY. LITTLE IS GAINED BY COPYING OLD METHODS AND MODELS. A DISTINCTIVE TYPE, THOROUGHLY UP TO DATE, SIMPLE, WITH NO HARD LINES AND YET STRONG, COULD BE EVOLVED WHICH WOULD BE RECOGNIZED AS AMERICAN.

Every European country is making this effort to EXPRESS ITSELF IN ITS OWN ARCHITECTURAL WAY. Germany has made a tremendous effort along this line, and that it has been largely successful is apparent to one who visits Berlin.

II.3 CPress clipping from The American Architect

Article published in The American Architect, mai 1912. Coll. part.

Beyond the four examples presented in this article, here is a (probably incomplete) list of other newspapers and magazines that reported on Guimard’s stay in the United States:

- The Daily Northwestern (April 2, 1912)

- The Indianapolis Star (April 7, 1912)

- Building Age (May 1912): “American Architecture as Seen by a Paris Architect”

- Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide (June 1, 1912): “American Architecture as Seen by a Paris Architect”

- The Concrete Age (June 1912): “French Architect’s Views on American Architecture”

III. SUMMARY

During his stay, Guimard’s opinion of New York architecture hardly changed, and upon leaving New York, the architect seemed as divided as he had been aboard Lusitania. In the Calumet and then the American Architect, he highlighted two fundamental flaws in skyscraper architecture: a lack of harmony and a lack of originality. As American architects were constrained by their clients, their art showed no distinctive features. It lacked vigor, harmony, specificity, and originality.

This judgment would be corroborated even more clearly twenty years later: on October 21, 1932, during a dinner with Louis Bigaux and Frantz Jourdain organized by Gaston Vuitton[17], Guimard echoed the following comparison regarding a building on the Champs Élysées constructed by the engineer Desbois: “What was said about the Eiffel Tower? It is, after all, a 300-meter monument that is less ugly than the first American skyscrapers.”[18].

Marie-Claude PARIS and Olivier PONS

Notes:

[1] The Cooper Hewitt Museum of decorative arts and design was founded in 1896 and opened to the public in 1897 thanks to Peter Cooper’s granddaughters, Eleanore Garnier Hewitt, Sarah Cooper Hewitt, and Amy Cooper Green. It was modeled after the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

[2] This exhibition will be held from November 18, 2022, to May 21, 2023, and then from June 22, 2023, to January 7, 2024, at the Richard H. Driehaus Museum in Chicago.

This exhibition on Guimard is not the first in the United States. For the record, the first major American exhibition took place in New York at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) from March 10 to May 10, 1970. It then moved to San Francisco at the Legion of Honor Museum from July 23 to August 30, then to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto from September 25 to November 9, 1970, and finally to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris from January 15 to April 11, 1971, where Guimard shared the spotlight with Horta and Van de Velde.

It was organized by F. Lanier Graham (assistant curator at MoMA), whom Adeline Guimard, then Hector’s widow, had met in New York, and above all thanks to the support of Alfred H. Barr Jr., the first director of MoMA, whom Adeline had contacted in 1945 and then met in Paris during her stay in June 1948.

In 1950, the Cooper-Hewitt Museum of Decorative Arts presented a few of Guimard’s works, then in 1951 the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon reassembled and presented Adeline’s bedroom at 122 Avenue Mozart in Paris.

[3] Edward Louis Oppenheim (born in Brussels on April 12, 1841) died of pneumonia in New York. An announcement of his death appeared in France in Le Matin on November 24, 1911. It is mentioned that E. Oppenheim was the father-in-law of Hector Guimard. At the time of his death, Edward was living with his daughter Nellie at the Netherland Hotel, 5th Avenue and 59th Street, New York. Renamed the Sherry Netherland in 1924, this hotel still exists at this address.

[4] Guimard was vice president of the Society of Decorative Artists in 1911, a role he shared with Paul Mezzara (1866-1918).

[5] According to American photographer Stan Ries, who took pictures of the Guimard Hotel in Paris.

[6] See Hervé Paul’s article entitled “Suzanne Richard, collaborator of Hector Guimard from 1911 to 1919” on the Cercle Guimard website (November 2021). Adeline Guimard painted a portrait of Suzanne Richard-Loilier, which she exhibited in 1922 at the Lewis & Simmons gallery, 22 Place Vendôme in Paris (portrait no. 28).

[7] The Lusitania was launched in June 1906 and made its maiden voyage in September 1907. It held the Atlantic blue ribbon for speed for two years before being dethroned by its sister ship, the Mauretania. During World War I, this ship was also used for transport and as a hospital ship before being torpedoed in May 1915 by a German submarine.

[8] Article published in Hearst’s Magazine, April 1912.

[9] This spelling is incorrect. The proper name “Julian” has only one “l.” The Académie Julian was founded in 1890 by French painter Rodolphe Julian (1839-1907). It has had various locations in Paris, the best known of which is at 31 rue du Dragon in Paris’s 6th arrondissement. Later, it took the name ESAG (Ecole Supérieure d’Art Graphique Penninghen), then simply Penninghen. Today, it is a private school of interior design, communication, and art direction.

[10] The Brevoort Hotel, located between 8th and 9th Streets in Manhattan, well known for a century for its restaurant (1854-1954), was demolished in 1955 and replaced by a luxurious 19-story building with 301 apartments (The New York Times, July 10, 1955).

[11] We recall the three principles that characterize Guimard’s art: logic, harmony, and sentiment.

[12] After their marriage, Hector and Adeline went on their honeymoon to Europe, specifically England and Berlin in 1909. This is attested to by postcards that Hector sent to his father-in-law in New York (New York Public Library). In addition, Hector participated in the Franco-British exhibition held in London in 1908.

[13] The words in capital letters here are also capitalized in the article in The Calumet newspaper.

[14] This refers to the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, which was postponed several times and finally took place in 1925. The United States was conspicuous by its absence.

[15] The Woolworth chain store building is located at 233 Broadway in southern Manhattan (Tribeca neighborhood). Built by architect Cass Gilbert (1859-1934), it has been designated a historic landmark and converted into apartments.

[16] The Singer factory building was erected in 1908-1909 and then demolished in 1967-68. Approximately 200 meters high, it was located at 149 Broadway.

[17] Gaston Vuitton (1883-1970) worked hard to enliven and illuminate the Champs Élysées, where his boutique was located (70 Avenue des Champs Élysées). He exhibited at the Salon de la Société des Artistes Décorateurs, of which Guimard was one of the founders.

[18] See Olivier Pons’ article “Vuitton, fan de Guimard” (Vuitton, fan of Guimard), Le Cercle Guimard, December 5, 2014.

Translation : Alan Bryden

Hector Guimard and Muller & Cie at the Castel Béranger: the end of a collaboration.

8 November 2024

As soon as they were completed in 1898, the facades of Castel Béranger caught the attention of passersby on Rue La Fontaine[1]. It must be said that their richness, both in terms of polychromy and ornamentation, was a stark contrast to the facades of the neighboring apartment buildings. At Castel Béranger, aquatic, botanical, medieval, and fantastical motifs[2] intertwine to enliven the cast iron, ceramics, and ironwork adorning the facades. This picturesque style, promoted by the public authorities at the time, even earned Castel Béranger one of the prizes in the 1898 facade competition organized by the City of Paris [3].

However, this rich decoration, which brought international fame to Castel Béranger and Hector Guimard, was not what the architect had originally planned. The elevations of the facades in the building permit submitted by Guimard in March 1895, which can currently be seen on display at the Paris Archives[4], prove this. The existence of these documents is not a discovery, as they have been known for a long time and are available for consultation. However, their high-definition scanning, carried out as part of the organization of this exhibition for the Guimard year, revealed an aborted ceramic decoration project. This was to be carried out mainly in collaboration with Muller & Cie, a company with which Hector Guimard had been working until then. Recent work by Frédéric Descouturelle and Olivier Pons, published in the book La Céramique et la Lave émaillée d’Hector Guimard[5], identifies most of the models that were to be used.

The initial Castel Béranger project

The Castel Béranger was commissioned by Élisabeth Fournier, a bourgeois woman from the Auteuil neighborhood. A widow wishing to invest her capital in real estate, at the end of 1894 she turned to the architect Hector Guimard, who also lived in the neighborhood, to build an apartment building on Rue La Fontaine.

With no constraints imposed by the client, the young architect designed a project based on the principles of Viollet-le-Duc’s rationalist school. The facade features picturesque architecture with medieval references, combined with a polychromatic effect achieved using different materials, painted cast iron and ironwork, and glazed ceramic decorations.

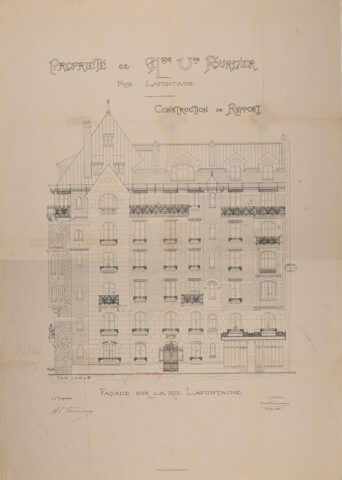

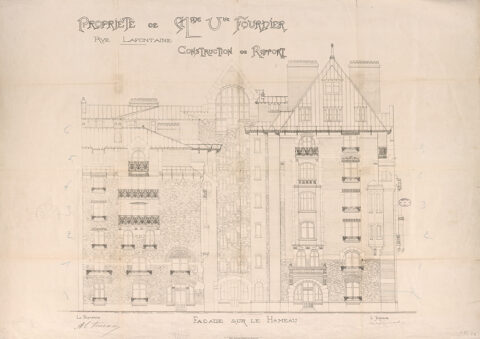

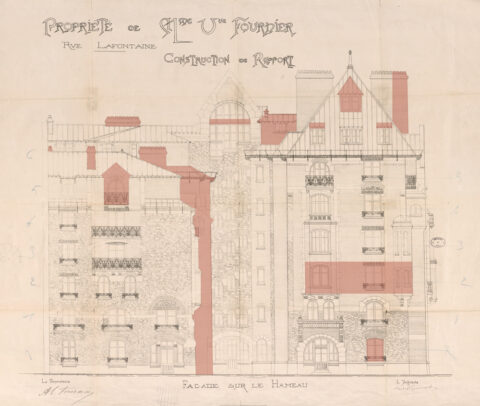

Before his trip to Brussels in the summer of 1895, Hector Guimard submitted the building permit for the Castel Béranger to the Paris Municipality during the second half of March[6]. This included plans for the different levels (basement plan, ground floor plan, standard floor plans, fifth and sixth floor plans) as well as elevations of the street and courtyard facades. It reveals a U-shaped building consisting of two structures organized around a courtyard, connected by a staircase. The building is aligned with the street, while the courtyard is open on the side of the Béranger hamlet.

Elevation of the facade on Rue La Fontaine of the Castel Béranger, building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

Elevation of the facade on the Béranger hamlet of Castel Béranger, building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

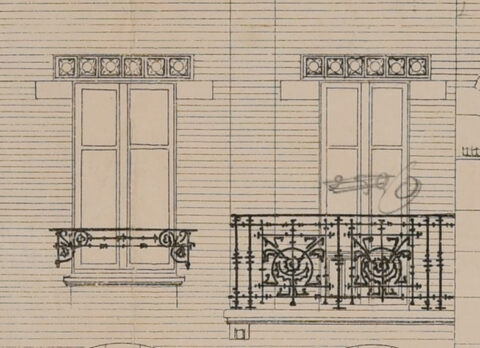

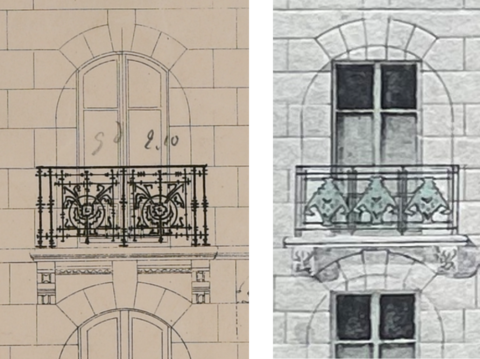

These drawings from the building permit are detailed enough to give a fairly accurate idea of the design that was planned at the time. The ironwork on the railings and the entrance gate reflect an undefined style that is fairly conventional and less daring than that of the Hôtel Jassedé, built two years earlier at 41 Rue Chardon-Lagache. However, floral stylizations can be seen.

Elevation of the facade on Rue La Fontaine of the Castel Béranger (detail), building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

The flower and leaves of the sunflower, the main motif of the Hôtel Jassedé decor, can indeed be recognized once again. It is possible that, from an economic standpoint, Guimard had planned to have the central motifs, which are repeated multiple times on the facades, made of cast iron. In any case, this is what he did in the final version of the balcony railings.

Central motif of the railings on the facades of Castel Béranger, elevation of the facade on Rue La Fontaine (detail), building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

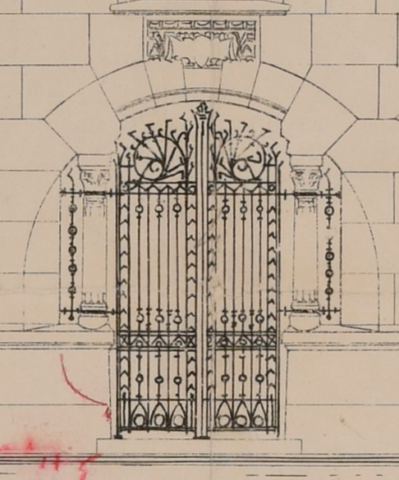

The ironwork on the gate is also not very inventive, with its evenly spaced vertical bars. Only at the top do two spiral motifs radiating outwards give it a more dynamic appearance.

Gateway to Castel Béranger, elevation of the facade on Rue La Fontaine (detail), building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

Above the storefronts of the two small shops in the last bays on the right, Guimard planned for a large sign to be inserted in front of a metal lintel. He designed a decoration interrupted by two smaller sign spaces placed in front of the spandrels of the first-floor windows.

Shop on the ground floor of Castel Béranger, elevation of the facade on Rue La Fontaine (detail), building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

This decoration is also naturalistic, with repeating floral motifs in two sizes. Probably intended to be in glazed ceramic, they appear to be framed by ironwork ending in semicircles, serrated like certain leaves, and separated from each other by floral spikes.

Decor of the shop sign on the ground floor of Castel Béranger, elevation of the façade on Rue La Fontaine (detail), building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

Castel Béranger and Muller & Cie

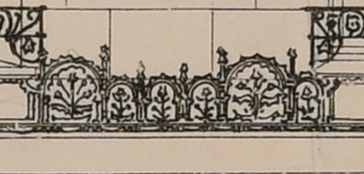

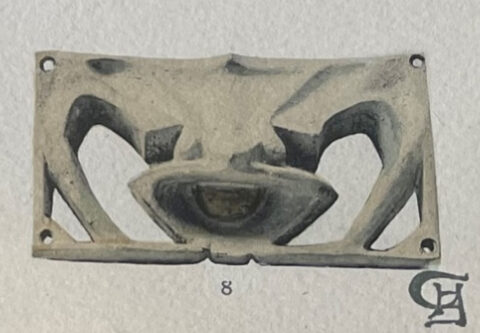

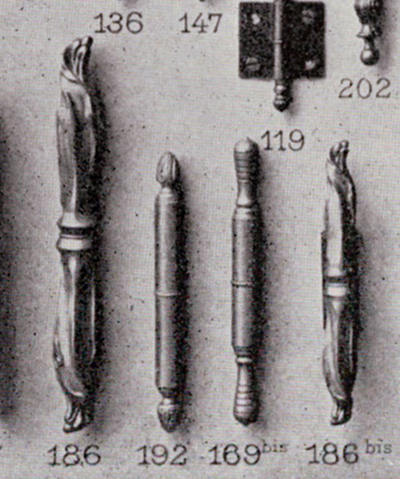

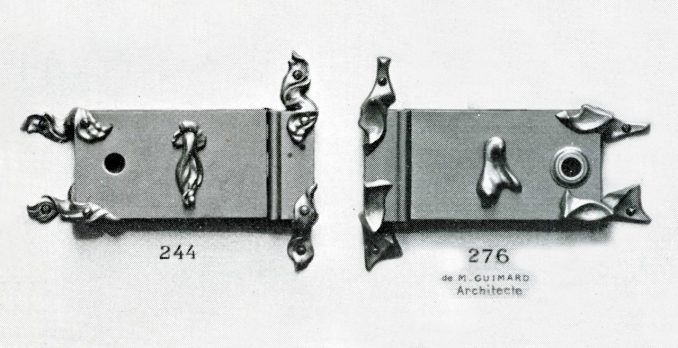

As shown in the building permit plans, numerous ceramic elements were planned for the facades. Thanks to the book devoted to Guimard’s ceramics and glazed lava[7], several elements of the original decoration have been identified in the Muller & Cie catalogs: metopes adorning the lintels, metopes decorating the spandrels, finials and friezes decorating the vestibule. These elements, produced and marketed by Muller & Cie, were designed and used by Guimard to decorate some of his projects prior to Castel Béranger.

Metopes and finials designed by Guimard and produced by Muller & Cie, shown in the facade elevations of the building permit for the Castel Béranger, building permit for the Castel Béranger, facade on Rue La Fontaine (windows) and facade on Hameau Béranger (finials), March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

In the initial project, Guimard had planned to reuse the lintel design created in 1893 for the Hôtel Louis Jassedé on Rue Chardon-Lagache[8]. As two years earlier, the metope model listed as number 13 in the second Muller & Cie catalog was to adorn the metal lintels of the windows of the Castel Béranger. The design of the facades shows that the metopes were to be enclosed in screwed iron frames, similar to the corbelled lintel of the Villa Charles Jassedé, also built in 1893.

Metope no. 13 designed by Hector Guimard and published by Muller & Cie; left: Muller & Cie, metope no. 13, Muller & Cie catalog no. 2, 1904, coll. Le Cercle Guimard; right: lintel of the Hôtel Jassedé, 1893, 41 rue Chardon-Lagache. Photo N. Christodoulidis.

The model used to decorate the spandrel of certain windows is metope no. 35 by Muller & Co. It was also used at the Hôtel Jassedé to embellish the base of the building. Although its appearance contrasts sharply with model no. 13, it was indeed designed by Guimard, as evidenced by the price list in the 1904 Muller et Cie catalog, which associates each model with the name of the architect who designed it.

Metope no. 35 designed by Hector Guimard and published by Muller & Cie; left: Muller & Cie, metope no. 35, Muller & Cie catalog no. 2, 1904, coll. Le Cercle Guimard; right: base of the Hôtel Jassedé, 1893, 41 rue Chardon-Lagache. Photo F. Descouturelle.

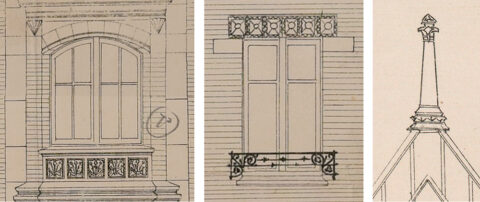

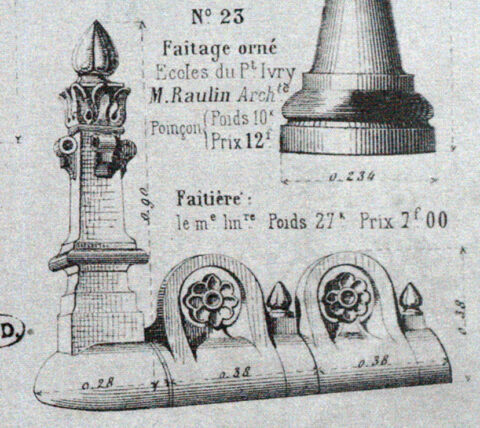

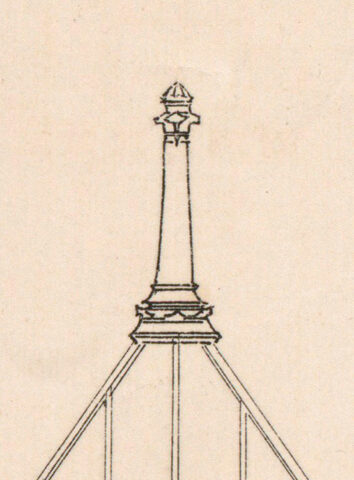

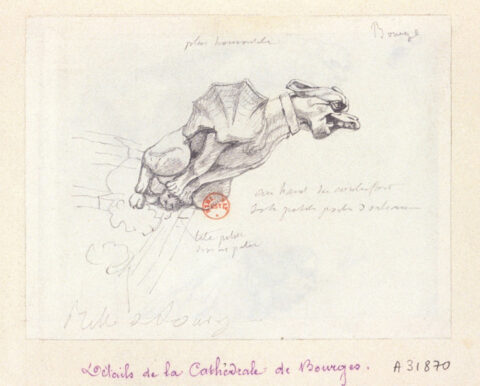

As is the case today, the pavilion roof at the left end of the building bordering La Fontaine Street was to be crowned with a ridge finial. Unlike the current finial, which appears to be made of cast iron, the original was to be made of ceramic and manufactured by Muller & Co.

The lack of detail in its representation in the building permit elevations makes it impossible to identify with certainty the model that was to be used. However, we can still hypothesize that it was a new transformation of finial no. 23 designed by Gustave Raulin[9] for the schools in Ivry-sur-Seine (1880-1882).

Roof finial no. 23 designed by Gustave Raulin for the schools of Ivry, Muller & Cie catalog no. 1, pl. 12, 1895–1896, coll. Bibliothèque des Arts décoratifs.

After using this model at the café-concert restaurant Au Grand Neptune in 1888, Guimard also used it to crown the roof of the Charles Jassedé villa in Issy-les-Moulineaux[10].

Roof of Charles Jassedé’s villa with finial no. 23 in Issy-les-Moulineaux, 1893. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

Shortly before, for the Hôtel Jassedé, he had transformed this finial by removing the side scrolls and adding scrolls taken from finial no. 22 in the Muller & Cie catalog.

Current state of a ridge finial on the Hôtel Jassedé, 41 rue Chardon-Lagache, Paris, 1893. Photo by N. Christodoulidis.

Although seemingly quite different from this latter variant, the design of the first version of the finial for Castel Béranger bears many similarities to the original finial no. 23. Like Raulin’s model, Guimard’s design features an end that resembles a flower bud. Both prototypes feature a spread of leaves at their base. The main difference lies in the round[11], elongated section and the absence of scrolls on the shaft.

Finial of the Castel Béranger, building permit, elevation of the courtyard façade, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

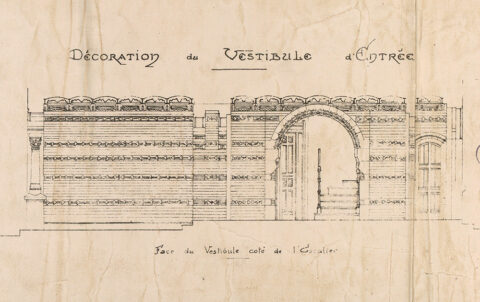

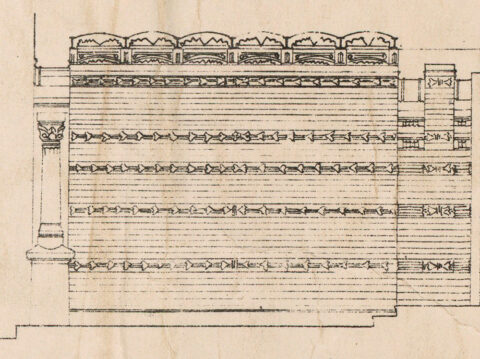

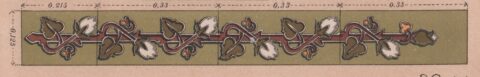

The walls of the vestibule, meanwhile, were initially intended to feature a design very different from the current one, consisting of bubbling sandstone panels created by Bigot. In a more traditional style, the walls were to be decorated with five horizontal floral friezes. Their appearance is similar to that of the vertical cloisonné panels used by the architect in 1891 to border the windows of the veranda of the Hôtel Roszé[12]. This is the model published under No. 127 in the second Muller & Cie catalog. Guimard seems to have planned to separate these friezes with beds of glazed bricks, in the style of the vestibule at 66 rue de Toqueville in Paris, created by Muller & Cie in 1897 under the direction of architect Charles Plumet[13].

Cross-section of the vestibule and hall of Castel Béranger, building permit, undated, detail, Paris Archives

Cross-section of the entrance hall of Castel Béranger, building permit, undated, detail, Paris Archives

Panel no. 127 designed by Hector Guimard and published by Muller & Cie, Muller & Cie catalog no. 2, 1904, coll. Le Cercle Guimard.

Detail of panel no. 125, cloisonné enameled earthenware, produced by Muller & Co., Le Cercle Guimard collection. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

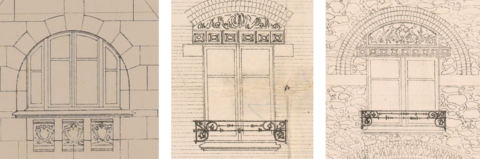

Two tympanums and a ceramic metope model, visible on the facade elevations of the Castel Béranger building permit, have not yet been identified in the Muller & Cie catalogs. It is likely that these pieces were also to be produced by the company[14]. However, it is also possible that Guimard had already planned to commission Gilardoni & Brault to produce them.

Metopes and tympanums designed by Guimard for the Castel Béranger, to be produced by an as yet unidentified company, building permit for the Castel Béranger, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives

During his stay in Brussels, Hector Guimard had the opportunity to meet architects Victor Horta and Paul Hankar, leading figures of Belgian Art Nouveau. In particular, he found in Horta’s work an integration of decoration and structure that was unparalleled elsewhere and which revolutionized his vision of modern architecture. After this trip, Guimard abandoned the figurative botanical decorations designed under the influence of Nancy[15] in favor of ornamentation that tended more toward abstraction. He borrowed the whip-like line motif from Horta, but he also drew on other, older sources[16].

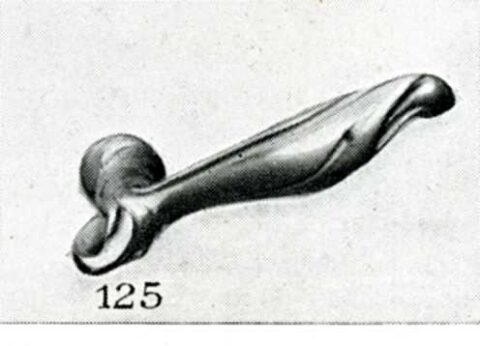

Thus, upon his return to Paris, Guimard redesigned the entire interior of the Castel Béranger, following the principle of the total work of art that had so impressed him in Horta’s work. In addition to designing the elements for the decoration and layout of the apartments (wallpaper, window handles, door handles, stained glass windows, fireplaces, etc.), the architect transformed all the ornamentation on the facades and in the vestibule.

Unlike the interior design, it was impossible for the architect to modify the plans that had already been drawn up, as the structural work had begun as soon as he returned from Belgium. A careful comparison of the plans and facades drawn up for the building permit with those published in the Castel Béranger portfolio[17] reveals that the layout of the spaces and the overall volume of the buildings are almost identical. The slight notable modifications (openings, turrets, chimney stacks, volume of the courtyard side of the building) are certainly the result of the natural process of the project, leading the architect to constantly question his work. These therefore undoubtedly appeared during the drawing up of the working plans for the structural work craftsmen, probably produced before Guimard’s departure for Belgium.

Elevation of the facade of Castel Béranger in the hamlet of Béranger, building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives. Color coding of structural modifications (in red).

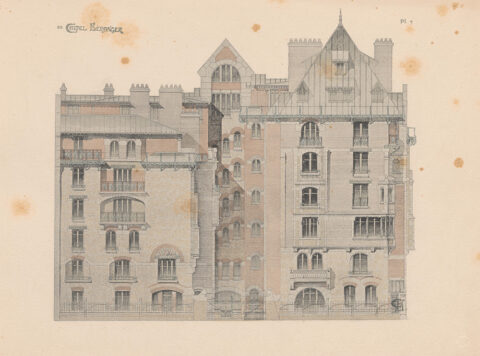

Elevation of the facade of Castel Béranger in the hamlet of Béranger, portfolio of Castel Béranger, pl. 7, 1898, ETH Library Zurich.

If we compare the drawings of the facades in the building permit application with those published after construction in the Castel Béranger portfolio, we see that all of the ironwork originally planned was replaced by alternative designs. The floral character disappeared in favor of a new style, partly abstract and partly fantastical.

Modifications to the design of the railings; left: elevation of the facade on Rue La Fontaine, building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives; right: elevation of the façade on Rue La Fontaine, Castel Béranger portfolio, pl. 2, 1898, Bibliothèque du Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

Similarly, all the ceramic decorations specified in the building permit were replaced. Guimard then ended his collaboration with Muller & Cie, even though a few months earlier he had been considering placing an order with them. This break was all the more surprising given that, until then, he had exclusively used Muller & Cie for all his projects requiring architectural ceramics: the café-concert restaurant Au Grand Neptune (1888), the Roszé hotel (1891), the Jassedé hotel (1893), the Charles Jassedé villa (1893), the Delfau hotel (1894), and the Carpeaux gallery (1894-1895). This change of suppliers benefited two competing companies. The first was Gilardoni & Brault, a tile factory which, like Muller & Cie, had diversified into architectural decoration. Metopes No. 13, produced by Muller and initially intended for window lintels…

Metope no. 13 published by Muller & Cie, window lintel of the Hôtel Jassedé, 41 rue Chardon-Lagache, Paris, 1893. Photo N. Christodoulidis.

…were thus replaced by new metopes, also encased in iron blades.

Metope probably produced by Gilardoni & Brault, window lintel from Castel Béranger. Photo by N. Christodoulidis.

As for the metopes No. 35 planned as spandrels for certain windows, they too have been replaced by new models.

Left: metope no. 35 produced by Muller & Co. and used for the base of the Jassedé hotel (41 rue Chardon Lagache, 1893), originally intended to adorn the spandrels of certain windows of the Castel Béranger; Right: metope produced by Gilardoni & Brault, ultimately used to decorate the spandrels of some of the windows of Castel Béranger. Photos by F. Descouturelle and N. Christodoulidis.

The second company Guimard turned to was Alexandre Bigot’s, which was still new but whose reputation was rapidly growing. It worked exclusively with glazed stoneware and was firmly positioned in the modern style.

Entrance hall of Castel Béranger, glazed sandstone by A. Bigot. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

Why did this collaboration with Muller & Cie come to an end?

There is no obvious explanation for this breakup. The reasons cannot be technical, since Gilardoni & Brault offered the same types of products as Muller & Cie, available in plain terracotta, glazed earthenware, and glazed stoneware. It is also doubtful that the break was solely for stylistic reasons. While Guimard’s sudden change in style may have come as a surprise to Muller & Cie, we know from its catalogs that the company welcomed new stylistic trends and produced a considerable number of modern designs.

On the contrary, until then, Gilardoni & Brault’s products had remained rather cautiously eclectic. Could this tile factory, suddenly enamored with modernity, have “poached” Guimard? In any case, the large order for his stand at the 1897 Ceramics Exhibition[18] confirms his interest in the architect’s new style, as he did not hesitate to bear the cost of manufacturing numerous molds. For several years, the company even supported Guimard’s research into shaped pieces, particularly vases.

Other, undoubtedly more petty reasons can be put forward to explain the emergence of a disagreement between the architect and Muller & Cie. First of all, Guimard may have been annoyed by the liberties taken by the tile factory with regard to his designs. The company did not hesitate to modify some of the architect’s designs and to create new models in a similar style, undoubtedly without paying him for them[19].

From Muller & Cie’s point of view, Guimard’s previous models had probably not been as successful as expected. When Guimard, instead of continuing to amortize them at Castel Béranger, proposed to create and publish new ones, the company may have backed away from an investment it considered too risky, choosing to end its seven-year collaboration with Guimard.

Maréva Briaud, Doctoral School of History, University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne (ED113), IHMC (CNRS, ENS, Paris 1).

Notes

[1] “Curious onlookers and astonished passers-by stopped to examine this original façade at length, so different from the surrounding houses.” L. Morel, “L’Art nouveau,” Les Veillées des chaumières, May 17, 1899, p. 453.

[2] This aspect will be discussed in a presentation at the Guimard study day organized by the Paris City Hall on December 3, 2024, and in the article that will follow.

[3] The results of the competition were not announced until 1899, and Guimard immediately had them engraved on the façade of the Castel Béranger.

[4] Guimard, architectures parisiennes, exhibition at the Archives de Paris, organized in partnership with Le Cercle Guimard, from September 20 to December 21, 2024. See also the exhibition journal available on site: Le Cercle Guimard. Exposition aux archives de Paris, no. 4, September 19, 2024.

[5] F. Descouturelle, O. Pons, “Guimard et Muller & Cie,” La Céramique et la lave émaillée d’Hector Guimard, Paris, Le Cercle Guimard, 2022.

[6] The building permit plans are dated March 10, 1895, and the facades are dated March 15, 1895.

[7] F. Descouturelle, O. Pons, op. cit.

[8] Ibid., p. 34.

[9] Hector Guimard was attached to Gustave Raulin’s studio during his studies at the École des Beaux-Arts.

[10] F. Descouturelle, O. Pons, op. cit., p. 42.

[11] The current finials on the roof of the Jassedé hotel garage are round in section. They are finial no. 4 in the 1903 Muller & Cie catalog, pl. 16, and may be the version of the model redesigned by Guimard ten years earlier.

[12] F. Descouturelle, O. Pons, op. cit., p. 31.

[13] Ibid, p. 21.

[14] Muller et Cie was able to produce any model on request.

[15] Guimard’s representations of flora are figurative but do not achieve the precision of Émile Gallé’s naturalistic drawings. They even slightly anticipate the stylizations of Eugène Grasset.

[16] See the article “Guimard and the auricular style” published on our website.

[17] H. Guimard, L’Art dans l’habitation moderne/Le Castel Béranger, Paris, Librairie Rouam, 1898. These watercolor plans are generally accurate but occasionally deviate from reality.

[18] National Exhibition of Ceramics and All Arts of Fire in 1897 in Paris, at the Palais des Beaux-Arts.

[19] F. Descouturelle, O. Pons, op. cit., p. 48.

Translation : Alan Bryden

Acquisition of a previously unseen copy of a Hector Guimard’s Cerny vase

2 April, 2025

As the deadline for submitting bids for a long-term lease on the Hotel Mezzara was rapidly approaching we continued our efforts, with regard to enriching our collections. Following the purchase of a section of a candelabra and its glass cover from the metro by Le Cercle Guimard[1], it is now the turn of our partner Fabien Choné to acquire, this time at auction[2], a new work by Guimard: a period copy of the Cerny vase.

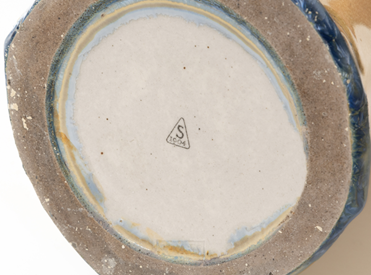

Cerny is one of three designs created by Guimard for the Manufacture de Sèvres around 1900[3]. Production spanned a decade, and our research in the institution’s archives has enabled us to estimate that no more than fifteen copies of the vase were manufactured by Sèvres during this period[4].

The appearance of an original copy of Cerny’s vase is therefore a minor event in itself, allowing us to identify and document the tenth copy to have survived to the present day. Made of glazed stoneware, it is characterized by a mustard yellow glaze enhanced by discreet blue crystallizations nestled in the hollows of the neck and highlighting its base, a color scheme that brings it closer to the examples preserved by the museums of Sèvres and Limoges.

Cerny vase auctioned on 13 March 2025. Photo étude Metayer-Mermoz.

At its base is the traditional HG monogram—which adorns all of Guimard’s Sèvres productions—as well as the Manufacture’s own marks on the bottom: the triangular S 1904 stamp, which allows it to be dated, and the rectangular SÈVRES stamp.

HG monogram engraved at the base of the vase. Photo étude Metayer-Mermoz.

Base of the vase bearing the two marks of the Manufacture de Sèvres. Photo étude Metayer-Mermoz.

An accident in the past necessitated restoration work last year—which we will return to shortly—involving the partial reconstruction of one of the four handles forming the neck.

The originality of this vase lies in its history and provenance, which, unusually for this type of object, are known thanks to family accounts.

Through direct descent, this vase comes from the former collection of Mr. Numa Andoire (Coursegoules 1908 – Antibes 1994), a soccer player and professional coach, famous for winning the French Championship in 1951 and 1952 while coaching the Nice team, OGC Nice, as well as the French Cup in 1952.

The Nice team in 1931. On the right, Numa is standing leaning on the wall. Photo all rights reserved.

The family story has it that the vase was given to Numa Andoire in 1927 by French President Gaston Doumergue (1863-1937) during a soccer tournament held to mark the unveiling of Antibes’ World War I memorial. The monument, whose centerpiece is a statue of a soldier sculpted by Bouchard[5], was built at the foot of Fort Carré and still overlooks the football field of the same name.

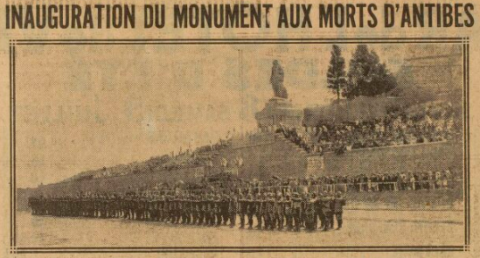

The regional and local press reported on the event, which took place on Sunday, July 3, 1927, with the usual patriotic speeches, troop parades, and medal ceremonies to the sound of the Marseillaise.

L’Excelsior 5 July 1927. Site internet BNF/Gallica

In attendance were a former undersecretary of state for war, who presided over the ceremony, a senator, a member of Parliament and a general representing the minister of defense, but no president of the republic… who was certainly represented by proxy, as is often the case for this type of event.

The presence of such a valuable Cerny vase as a gift from the state on the occasion of a relatively insignificant competition may seem surprising. But it should be seen in the context of the long (and sometimes unusual) history of generosity granted by the authorities on the occasion of cultural, scientific or sporting events. It should be remembered that the State, the sole shareholder of the “Manufacture de Sèvres”, used it primarily to provide valuable diplomatic gifts, but also a large number of art objects presented on behalf of the authorities at cultural and sporting events. World, international, and regional exhibitions were thus an opportunity to present numerous vases, statuettes, and other decorative dishes—most often with the famous blue background of Sèvres—whose size and decoration were more or less correlated with the importance of the prizes awarded to the winners, rewards that were variously appreciated by the artistic community…[6].

As for our Cerny vase, presented more than 15 years after the last one was made in Sèvres, this was probably one of the many occasions on which the State drew on the reserves of official manufacturers to award first prizes, when it was not the institutions or ministries themselves that disposed of certain acquisitions. In 1927, at a time when Art Nouveau was already well out of fashion, the authorities probably did not realize that they were offering an object that, a century later, would acquire such significant artistic and financial value.

Why did our vase become the property of Numa Andoire rather than another player? As the family story is not sufficiently clear on this point, we can only speculate. Was it to reward the short but promising career of the young prodigy player from Olympique d’Antibes, or rather to offer him a farewell gift as he completed his seventh and final season with the Antibes team before joining the Nice team? Probably a little of both… In any case, it is touching to note that this vase was kept for a long time as a family heirloom before the heirs finally decided to part with it.

This unique Cerny vase now features prominently in our museum layout project for the Mezzara hotel.

Olivier Pons

Notes

[1] https://www.lecercleguimard.fr/fr/une-verrine-en-verre-du-metro-de-guimard-pour-notre-projet-museal/

[2] Sale on March 23, 2025, Metayer-Mermoz auction house in Antibes, expert E. Eyraud.

[3] The other two forms are the Chalmont plant pot and the Binelles planter.

[4] For more information on the history of this collaboration, readers are referred to the book published in 2022 by Éditions du Cercle Guimard: F. Descouturelle, O. Pons, La Céramique et la Lave émaillée d’Hector Guimard.

[5] Henri Bouchard (1875-1960) had a studio built in 1924 at 25 rue de l’Yvette in Paris (75016), opposite the property of the painter Jacques-Emile Blanche, for whom Guimard carried out decorative work. The sculptor’s studio, which became the Bouchard Museum, closed its doors in 2007 before being transferred to La Piscine in Roubaix.

[6] One of the most famous cases is probably that of François-Rupert Carabin (1862-1932), a rebellious sculptor who, in 1912, received a blue-bottomed Sèvres vase as the “Prix du Président de la République” (President of the Republic Award), which he considered “very ugly and second-rate.” He then created a pedestal consisting of three female figures turning away in horror and exhibited it shortly afterwards at the Salon de la Société nationale des Beaux Arts in order to display it during the presidential visit. The pedestal and the vase now belong to the Perrier-Jouët collection in Épernay.

[7] In 1905, for example, the Ministry of the Navy acquired a Cerny vase that had left the Sèvres workshops a year earlier, and was therefore dated 1904, like our vase…Translation: Alan Bryden

The fantastic and colorful bestiary of Castel Béranger

12 January, 2025

The Cercle Guimard has already devoted several articles to the Castel Béranger, the apartment building commissioned by Élisabeth Fournier[1] from Hector Guimard in 1894 and completed in 1898. Our last article [2] showed that the complete stylistic overhaul carried out by Guimard during its construction from 1895 to 1898 coincided with a change in suppliers for the ceramic decorations. This time, we focus on the fantastical and colorful bestiary that adorns its facades, first presenting the unique features of this project, then the fantastical dimension of its decor inspired by nature and the neo-Gothic repertoire. Finally, the materiality and polychromy of this bestiary will be explained.

“This building, […], is set to revolutionize the art of construction. Its appearance is truly extraordinary”[3].

As reflected in these comments made by a journalist in an article dedicated to Castel Béranger, yesterday as today, the facade of this building does not go unnoticed in the public space. The fact that it was one of the winners of the facade competition organized by the Paris City Council in 1898 testifies to the desire of the public authorities at the time to encourage architecture that broke with the monotony of the facades of traditional Haussmann-style apartment buildings, “which made the streets of Paris boring enough to put you to sleep”[4]. Its construction coincided with the work of the commission set up to draw up new road regulations allowing greater freedom in the silhouettes of buildings and their projections.

The Castel Béranger project: modifications and unique features

A design far removed from the initial project

However, this rich decoration, which brought international fame to Castel Béranger and Hector Guimard, was not what the architect had originally planned. A look at the facade elevations in the building permit application submitted by Guimard in March 1895 reveals an initial design that was never realized. After his stay in Brussels in the summer of 1895, during which he met architects Victor Horta (1861-1947) and Paul Hankar (1859-1901), Guimard redesigned the entire interior of Castel Béranger. This is how a fantastic and colorful bestiary appeared on the facades, but also inside the building.

A bestiary on the facade: the only example in Guimard’s work

The term “bestiary” is used here in the same way as it is defined in the Larousse dictionary, namely as “the whole of animal iconography, or group of animal representations”[6]. Looking at the facades of Castel Béranger, it is easy to identify elements of the decor that are rather figurative in nature, inspired by wildlife. The shape of a cat is easily recognizable.

Panel depicting a cat arching its back, made of glazed sandstone from Castel Béranger, created by Gilardoni & Brault in 1897. Photo by Nicholas Christodoulidis.

The central motifs of the cast iron balconies are half human, half feline. Their large noses may even evoke the muzzle of a lion, a recurring motif in 19th-century ornamental cast ironwork.

Central motif of the cast iron balconies of Castel Béranger, produced by the Durenne foundry in Sommevoire between 1895 and 1898. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

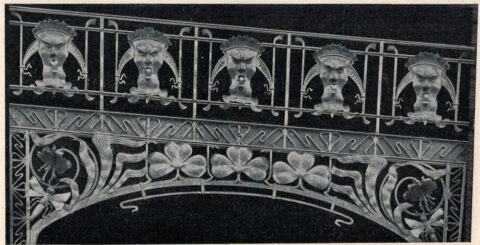

However, the bestiary of Castel Béranger also includes several motifs that are more specifically related to underwater fauna and contribute to a broader aquatic repertoire[7] in this apartment building.

The most convincing example is undoubtedly the decorative cast iron chain anchors, whose formal appearance resembles that of a seahorse. These structural elements, which appear numerous times on the facades, are the ends of tie rods that contribute to the chaining of the construction, allowing the distribution of tensile forces in the masonry and the solidarity of the walls (and possibly the floors) between them. It is for this reason that Guimard added what could be described as two legs to these sea horses.

Cast iron anchor from Castel Béranger, made by the Durenne foundry in Sommevoire between 1895 and 1898. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

Inside, the starting point of the staircase handrail may also evoke the silhouette of a horse’s head and neck[8].

Start of the handrail on the staircase of the building on Rue du Castel Béranger, carved wood. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

Once again outside, on a tympanum of the building overlooking the courtyard facing the hamlet of Béranger, there is a fish between two shrimps.

Glazed ceramic tympanum on the courtyard façade overlooking the hamlet of Béranger, created by Gilardoni & Brault between 1895 and 1898. Photo by Nicholas Christodoulidis.

This decorative animal register is an exception in Guimard’s work. Although some cast iron elements from Castel Béranger were later reused by the architect in some of his other projects[9], no other decoration of such magnitude featuring fauna preceded or followed it in his built work.

The fantastical decoration of Castel Béranger

A fantastical dimension…

Castel Béranger was not only unique in the diversity of polychrome materials used in its masonry. It was also unique in the profusion of chimeras adorning its facades, a veritable fantastical bestiary. According to the Larousse dictionary, the fantastic “refers to an artistic work […] that transgresses reality by referring to dreams, the supernatural, magic, and horror[10].”

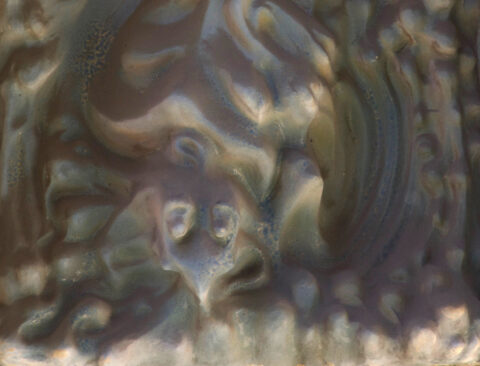

This “transgression of reality” is a key concept in understanding the decoration of this apartment building. Unlike his initial project, in which he had planned a stylized botanical decoration, the architect ultimately designed a decoration that no longer sought to reproduce nature as it appears to us. Instead, it oscillates between a “modified” realism, as in the cast iron seahorses or the cat panel, where the modeling of the animal’s body is extended by three-dimensional curves…

Nicholas Christodoulidis (photographer), Panel depicting a cat arching its back, made of glazed sandstone at Castel Béranger, created by Gilardoni & Brault in 1897. Photo Nicholas Christodoulidis.

… and a more or less advanced abstraction, such as, for example, on the panel decorating the corbel of the bow window in the courtyard, where the modeling appears so abstract, so shapeless, that at first glance it seems futile to look for any similarities with an element of fauna or flora.