Month: September 2020

“National”, “Style Nouveau”, “Architecte d’Art”, “Style Guimard” and “Style Moderne”, the qualifiers applied by Guimard to his work and its posterity

Is there not a little demiurge in every architect? Rare are the professions in which, under the impulse and the plans of a single personality, a concrete work rises ex nihilo, which generally survives him. While most of them are aware of this, few declare that their ambition is not to revolutionise their profession, but to create a style so personal that it is worthy of bearing their name. Hector Guimard dared to do so.

All the art historians who have studied Guimard’s work have not failed to note the immoderate use of the various qualifiers he used for his work. Secretly sorry or implicitly admiring his audacity in using the term “Style Guimard “, they have noted that this display of pride made him the object of mockery, and assumed – no doubt rightly – that it had led to enmity, which undoubtedly contributed to his isolation from the contemporary art world. If it is perfectly true that the major French media dealing with decorative art, after having briefly taken an interest in him during the time of the Castel Béranger, then turned a blind eye to him, we now know that Guimard has always displayed an intense sociability that has partially compensated for this lack of recognition. In this article, we will try to better define these different qualifiers and the times in which Guimard may have used them. We will see that they do not follow one another in a linear fashion over time, as one might have thought, but are rather used according to his needs or desires.

- « National »

A player in the early days in France of what we now call the Art Nouveau style, Guimard undoubtedly very quickly perceived the interest he had in finding a name for his creation on his own before the public, or rather the media, would do it for him. It was also appropriate that this name should distinguish him from other renovators of architecture and decorative art. The name “Art Nouveau style” had already been used previously in Belgium. Moreover, in 1895, a key date marking the beginnings of the creation of Castel Béranger, the name had also become a Parisian commercial name with the opening of the L’Art Nouveau Bing gallery by the German-born merchant Siegfried Bing[1], who presented and sold a vast selection of French, European and American production in this style. It is understandable that it was therefore difficult for Guimard to accept this patronage for his personal work. The acute awareness that he had of the value and originality of his creations certainly pushed him to find a qualifier that did not assimilate them to what was very quickly perceived by the press as foreign imported art — in turn seen as Belgian or English — and which was the subject of xenophobic (and anti-Semitic) rejection from the opening of the L’Art Nouveau Bing gallery[2]. This last episode is to be seen in the context of nationalist unrest which only grew for a decade before the climax of the Dreyfus affair in 1898 and which then saw the clear victory of the nationalist right in the municipal elections in Paris in 1900. Logically, this xenophobic rejection led to a media exhortation to create a modern style that was truly French, a leitmotif that seemed to many critics to find its fulfilment in the elegant and quiet buildings of architect Charles Plumet. His work, which was unanimously acclaimed, was seen as a final avatar of the French Renaissance. But Guimard, whose conversion to the modern style was intimately linked to his discovery in 1895 of the work of the Belgian architects Hankar and Horta, found himself in a more ambiguous position. Several clues prove that he tried to escape the anathema of cosmopolitanism that could be thrown at him at any moment.

From the first of his three articles devoted to Castel Béranger[3] in 1896, the architect Louis-Charles Boileau had lit a counterfire to this accusation of foreign inspiration by pointing out to his readers that Guimard’s wallpapers were “not English”[4]. This clarification, no doubt made at Guimard’s instigation, is twofold. First of all, it may, by antithesis, help the reader to better situate Guimard’s style by opposing it to the English style in terms of wallpapers, a style then well-known and well recognisable. But it also intends to place itself on a political and nationalist level.

Shortly after Boileau’s article, in January 1897, Charles Genuys, a former Guimard professor at the National School of Decorative Arts, published an article in La Revue des Arts Décoratifs vigorously entitled “Soyons Français! “(“let us be French”) in which he warned against the temptation that modern decorative artists might be tempted to follow in the footsteps of foreign artists, especially Belgians. Here Genuys is aiming at the so-called “Belgian line”, the trend led by Henry Van de Velde who, unlike Horta, refuted any idea of inspiration from nature to build a purely linear and abstract decor and structure. This text by Genuys, which in fact supported Guimard’s efforts, could however also resonate as a warning to those who, although they say they always want to refer to the inexhaustible spectacle of nature, nonetheless favour arrangements of abstract lines.

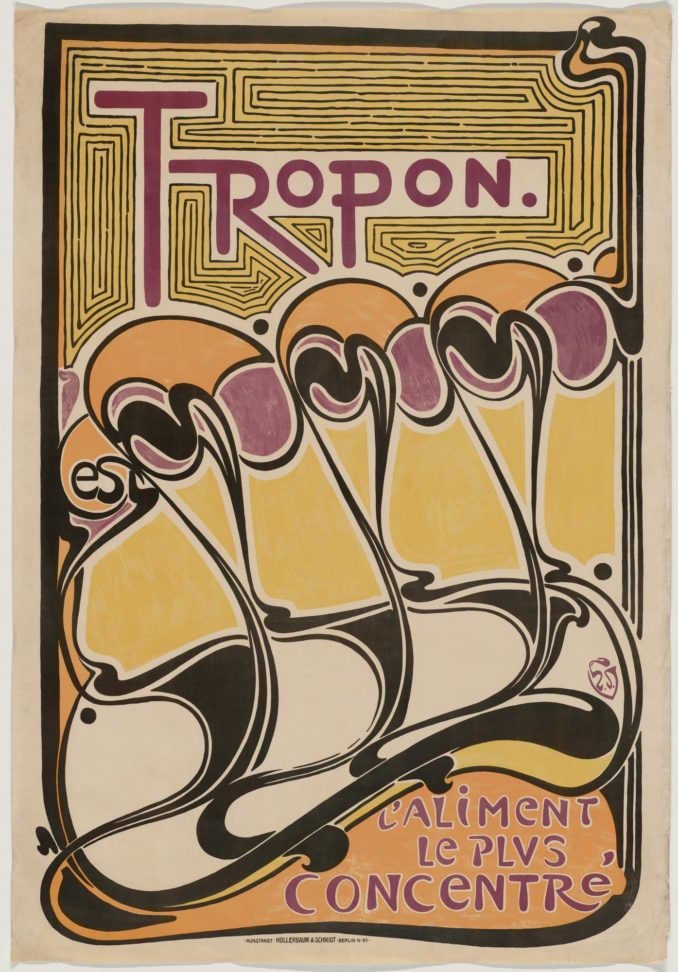

Henry Van de Velde, poster for the Tropon brand, 1898. MoMA photo. This lithograph is inserted in the magazine L’Art Décoratif in 1898.

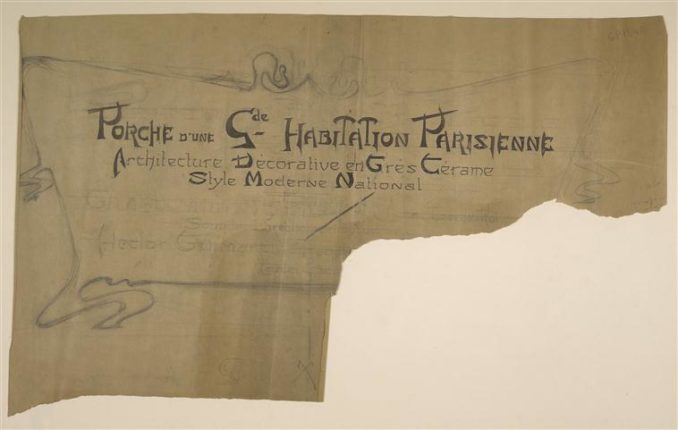

This gives a better understanding of the name of the stand designed by Guimard for the company Gilardoni & Brault at the Ceramics Exhibition at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in 1897[5]. It reads that the porch of a large Parisian dwelling on display is in the “National Modern Style”. Although ephemeral, the use of this term did not escape the notice of the decorator Eugène Belville[6]. In the magazine Notes d’art et d’archéologie of 1897, he ironised on his use by Guimard who, he wrote, “epigraphs his madreporic constructions with the title of “National Modern Style”. He warned him against the pretension that some people have of “making a style” that could “raise public mistrust” as opposed to those who would “content themselves with looking for style”.

Project for a sign for the Gilardoni & Brault stand at the Ceramics Exhibition in 1897. Porch of a Large Parisian dwelling in glazed stoneware/Architecture Décoratif en Grès Cérame/ Style Moderne National/par/Gilardoni Fils et A. Brault Tuilerie de Choisy le Roi/under the direction of…/Hector Guimard Architect…/… Ink and graphite on tracing paper, Musée d’Orsay, Guimard collection, GP 1840.

We will see that the debate on whether Guimard’s style is indeed a French style resurfaced in 1898 and 1899, at each event organised by the architect around the Castel Béranger. Thus, in enthusiastically reporting on the publication of the Castel Béranger portfolio in Le Moniteur des Arts of 28 January 1899, its director Maurice Méry, does not want to admit that he could have been inspired by the Belgian example:

“All this, for once, I am happy to note, is the work of a Frenchman, one of our own, who did not seek his inspiration abroad […]”.

While a broader-minded and more perceptive author, the writer Octave Uzanne, admits that a foreign influence, Belgian in this case, could revitalise modern French architecture. Thus, in a text dated 29 November 1898, but published in 1899 in his book Visions de Notre Heure, Choses et gens qui passent, he believed he had found in the person of Guimard the providential architect who seemed to be sorely lacking in Paris. As he wandered around the capital, denouncing “the disturbing imaginative torpor of its architects”, “the silly ordering of its buildings” and its “stupid architectonic”, he marvelled at the originality of Castel Béranger and its “somewhat revolutionary architecture”, the fruit, in his opinion, of “a matured thought […] tending towards the renovation of architectural art”. Happy, almost astonished to have “unearthed this work built and executed in Paris”, he drew on the example of Belgium and its current architectural revolution — led by Victor Horta in particular — to express the wish that Guimard would impose himself in the same way in France as a leader of modern architects:

“May Mr. Hector Guimard soon become our Horta for France!”

But other authors, more narrowly “French-biased” have rejected this idea. This is the case of Édouard Molinier in his article published in Art et Décoration in March 1899, who wrote about Castel Béranger:

“Without denying Horta’s merit, there was perhaps better things for a French artist to do than to seek his inspiration in Belgium. We would have preferred to witness an attempt, however incomplete, to resurrect the old French style.”

Shortly afterwards, on 15 April 1899, in his article on the results of the first Paris façade competition for which Castel Béranger won an award, a journalist from L’Illustration agreed with Molinier:

“It would be easy to quibble with M. Guimard on many details; one could ask him mischievously if he had not found creative inspiration in Belgium.”

Even if the only occurrence of Guimard’s use of the adjective “national” that we know of is that of the sign on the Gilardoni stand in 1897, we suspect that he continued to use it at least orally until the beginning of 1899. As proof of this, we refer to the text of an article published in Le Monde Illustré of 8 April 1899, also devoted to the competition for the facades of the city of Paris, but quite opposed to the persiflage of the article in L’Illustration which appeared a week later. This first article was signed “G. B.”. Could it be Georges Bans, one of Guimard’s close publicists, also editor of the magazine La Critique? In any case, its author, captivated by the architecture of Castel Béranger, in view of the formulas and arguments used, probably met Guimard on the spot. He ends his article with a vibrant affirmation of the national character of his work:

“[…] because the “Castel Béranger” is a very French work, and despite its spontaneous and revolutionary appearance, it is directly linked to the traditions of our modern art and national life.”

This sentence is surprisingly close to the conclusion of one of the two texts appearing in the opuscule entitled Études sur le Castel Béranger, signed “PN”, initials under which one agrees to recognise Paul Nozal, a close friend of Guimard and son of his future client and associate, Léon Nozal. This study was published at the time of the Castel Béranger exhibition in the salons du Figaro, from 5 April to 5 May, and was extended until 20 May, without the precise date of publication[7] being known, so that we do not know whether G. B. reduced the PN sentence or whether, on the contrary, it was PN that amplified G. B.’s sentence:

“Yet there is one thing I would like to repeat in closing: Castel Béranger is a very French work, it is that despite its spontaneous appearance, it is directly and profoundly linked to the traditions of our art of national life, and that under a new expression it is indeed a product of generations slowly hatched and matured in the same climate, a product of our soil and our race.”

- “Style nouveau”

For his part, Guimard seems to have abandoned this rhetoric, which today would be described as identity-based, but which will remain widespread in the press for several decades to come. Indeed, on the invitations to the exhibition devoted to the Castel Béranger in the premises of Le Figaro, which opened in April 1899, he mentioned that these were “compositions in a new style”.

Invitation card for the exhibition on Castel Béranger in the premices of Le Figaro in 1899 (detail). Private collection.

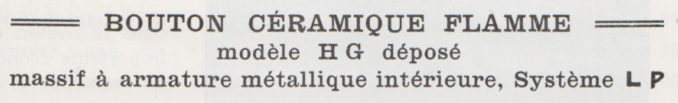

This new expression, no doubt too close to “Art nouveau”, was then no longer used, with one exception. In 1911, the hardware house Paquet in Grenoble, France, at the request of the architect, undertook to use the formula “Modèle Style Nouveau H.G.”[8] to designate the porcelain doorknob it manufactured for Guimard. In reality, however, the wording used in the published catalogue retained the architect’s initials, while deleting the “Style Nouveau”.

Paquet Catalog (detail), without date. Private collection. The name “Flame” which is given to the Guimard porcelain button does not seem to have been used previously.

- “Architecte d’art” (art architect)

On the plans of the Villa Canivet[9] dated 13 and 20 April 1899, the words “Architecte d’Art” appear in the stamp. Although it is possible that the stamp was added later on this plan, as early as the following year, at the time of the Universal Exhibition, Guimard used this term. He remained faithful to it for at least a decade, since it still appeared on his wedding announcement in 1909.

Announcement of the wedding of Hector Guimard and Adeline Oppenheim in 1909 (detail). Private collection.

Guimard simply meant that he wanted to give his entire production an artistic character that would distinguish it from ordinary architectural and decorative productions. A few years later, in 1908, the title “Artistic fonts” in his catalogues published by the Saint-Dizier foundry was part of the same qualitative inflation by wanting to indicate a production with a true artistic character, unlike almost all the other ornamental fonts on the market. But doesn’t wanting to distinguish oneself from the others by pointing out its eminently artistic quality also mean belittling one’s own? We know the artisanal and manual character of the usual work of a blacksmith or carpenter. And it is therefore easy to accept that he is known as an “ironworker of art” and “carpenter of art” when his production deserves it. However, it is much less well accepted that an architect, who is assumed to have studied at the National School of Fine Arts, should call himself an “Architect of Art” (especially with capital letters).

Letterhead of a letter from Guimard to the director of works of the CMP, dated 27 January 1903. Guimard used the same design on correspondence cards, also used in 1903. Coll. RATP.

The first press article referring to this term was probably Pascal Forthuny’s[10]description of the furniture at the Universal Exhibition, published in the magazine Le Mois littéraire et pittoresque in December 1900:

“M. Guimard — by what concept is he blinded? — claims to be an art architect (!) and to have created a style! […] And what does this mean? And finally, does an individual create a style? And does Mr Guimard have the right to deny his origins?”[11]

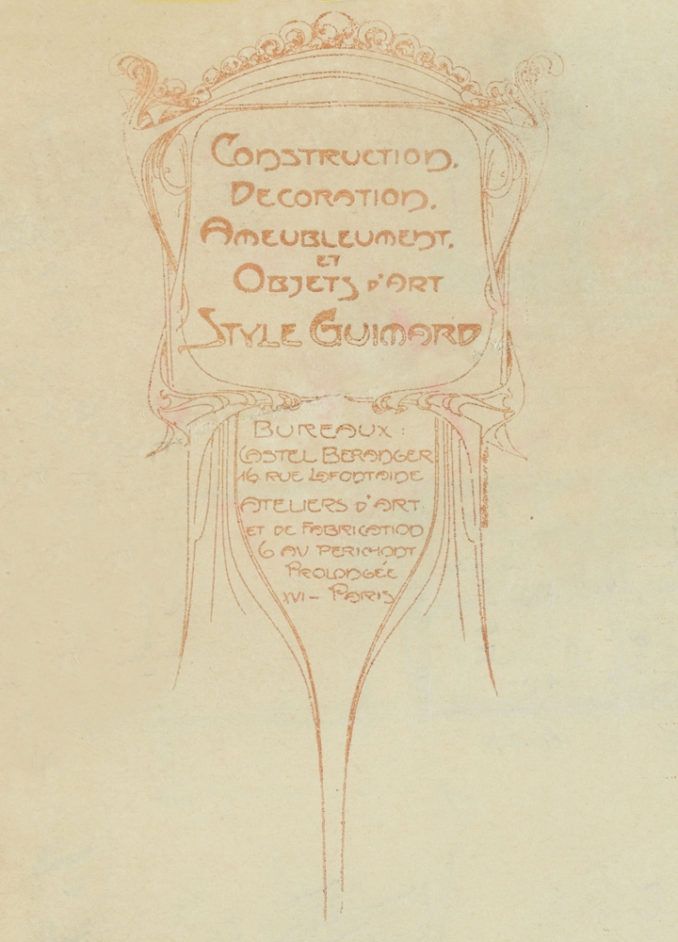

- “Style Guimard”

These last words of Forthuny’s article “and to have created a style” suggest that Guimard also began to use the term “Style Guimard” at this time. This is confirmed by Eugène Déjardin’s order for his “Déjardin French Malt Extract” stand at the World’s Fair for a series of “Guimard-style Vikado[12] showcase furniture”.[13]

Letter head of an invoice from the Ateliers Guimard dated 14 November 1905. Musée d’Orsay, Guimard collection, GP 128.

In 1901, just a few months after the publication of Forthuny’s text, the magazine La Vie Moderne published an anonymous but fascinating article entitled “Le Style Guimard”. It is probably one of the most accomplished texts from this period on the subject. Drawing on his most recent works such as the Castel Béranger or the accesses to the metro – which he commented favourably – and then on the architect’s career and personality, the author does not at any time seem be shocked by the use of this expression. On the contrary, he offers a detailed explanation, justifying its use by the logic that animates his constructions, the harmony of a naturalistic style skillfully drawn from the historical repertories while being rid of its superfluous ornaments and the beauty of a line whose finesse and simplicity he underlines:

“…the curves, the inflections of these lines obey a general idea; a preconceived theory whose realisation confers on the object a distinctive mark, an originality of its own, a personal style which is, why not say it? the Guimard Style.”[14]

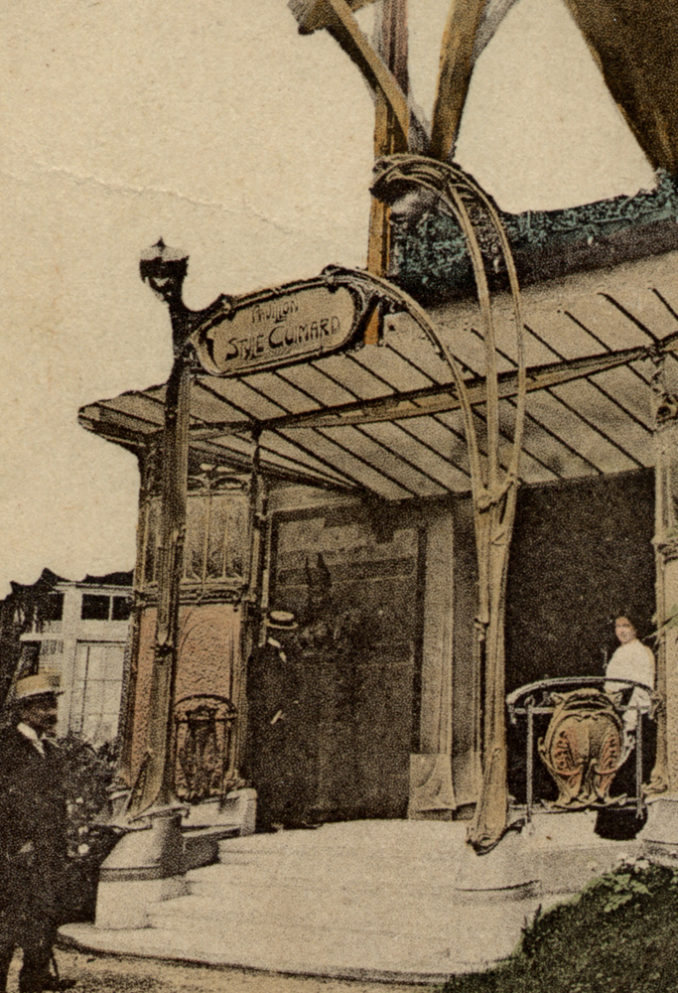

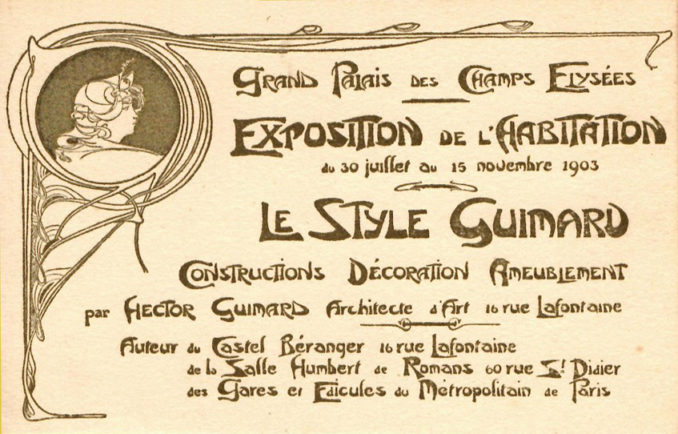

From the World’s Exhibition onwards, a debate began with articles on the legitimacy of the architect giving his name to a style. Guimard has never been as disturbing, arousing contrary feelings and irreconcilable positions, as at that time, considered to be one of the key periods of his career. The controversy reached a climax three years later at the Housing Exhibition at the Grand Palais in 1903, when the words “Pavillon Style Guimard” were clearly displayed on the enamelled lava sign on the porch of Guimard’s pavilion.

The porch of Guimard’s pavilion at the Housing Exhibition at the Grand Palais in 1903. Postcard n°1 of the series Le Style Guimard (detail). Private collection.

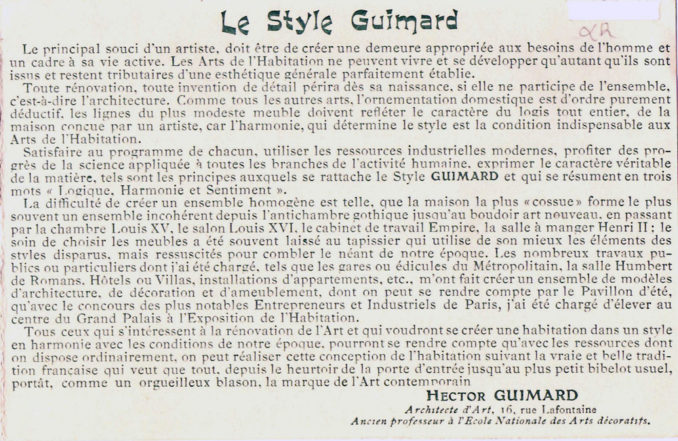

It accompanied that of “Architect of Art” on the series of postcards sold on this occasion. It was also the subject of an explanatory text entitled “Le Style Guimard” which appeared on the leaflet used to wrap the cards and on the back of the leaflet accompanying the lecture he gave on 27 October at the Grand Palais. Guimard set out his architectural principles based on the “Logic, Harmony and Feelings” trilogy he had developed since his 1899 lecture at the Salon du Figaro[15].

Invitation to the inauguration of the Pavilion Le Style Guimard at the Housing Exhibition at the Grand Palais in 1903. Private collection.

Text by Guimard printed on the leaflet for the lecture he gave on 27 October 1903 at the Grand Palais. Private collection. It is accompanied by the same text by Stanislas Ferrand (previously published in the magazine Le Bâtiment on 9 August 1903), which also appears on the packaging of Le Style Guimard card packs.

Seen by many as an unbearable lack of modesty, this “Style Guimard ” mention was, of course, just as badly received as the qualifier “Architect of Art”. In addition to the singularity of this term, singular since no other contemporary artist, decorator or architect has ventured to imitate it, its use also implies a break with the past and the process of linking one style to another. This is what Forthuny wanted to denounce by writing: “Does Mr. Guimard have the right to deny his origins?” That is to say, does Guimard not want to admit what he owes to medieval art, Baroque art, Oriental art and more recently to Horta, Hankar or Van de Velde? Some critics have therefore not accepted that a contemporary artist might want to give his name to a style when the great decorators of the past did not have this pretension. This opinion prevailed in the major decorative art magazines, such as Art et Décoration, in which an anonymous article was published in October 1903 commenting on the Housing Exhibition at the Grand Palais:

“M. Guimard, in his pavilion, offers us an unbalanced mixture of good and bad things. The artist still needs to settle down a little. But what a strange pretension leads him to decorate his work with signs informing visitors that they are allowed to admire the Guimard Style! I don’t think that our great decorators, Du Cerceau, Meissonnier, have ever baptised their style in this way, and yet…”

On the contrary, the newspaper La Fronde came to his rescue. This leading feminist daily, engaged in many progressive struggles, at the forefront of which was the demand for the place of women in society, did not specialise in decorative art. But its article of August 16, 1903, entitled “Le Style Guimard” and signed La Dame D. Voilée (the veiled D. Lady)[16] …, considered the criticisms of Guimard to be excessive:

“Did [those who despised the Guimard Style] notice in the night, all the way over there at the Porte Dauphine, two large fireflies shining through trees and shrubs, with a mysterious charm, these are nevertheless two kiosks of the Metropolitan. What sign, what gas ramp or electric advertisement would be both more meaningful and more elegant than these two phosphorescent cages that so kindly indicate the location of the Metro stations”.

At the end of that same year 1903, in the same way as in Art et Décoration, Guimard was severely attacked by the art critic and specialist in the history of French furniture Roger De Félice in his review of the Salon d’Automne published in the magazine L’Art Décoratif. His commentary on Guimard’s submission (consisting of watercolour drawings) first of all makes ironic use of the adjectives “Architect d’Art” and “Guimard Style” before claiming that these proud references are only there to enhance an unnecessarily complicated work:

“Mr. Hector Guimard also presents us with projects of decorative ensembles, but in the form of simple watercolour sketches. M. Guimard plunges the public into great perplexity. His card is there, bearing these words engraved in singular characters: Hector Guimard, Architect of Art. And the public wonders: What can be, an Architect of Art? And above all an architect who is not an architect of Art? We have never seen M. Plumet, for example, who is indeed an authentic artist, and a great artist, declare himself to be an Architect of Art. The public is approaching and searching. It learns first of all, from M. Guimard himself, because he proclaims it on many labels, the existence of a Guimard Style. […]. Art’s architecture consists of course in the horror of the simplicity and straight lines which, curving, hunchbacking everything, go so far as to give simple pillows a cleverly contoured shape… And also in refinements such as these inclined planes replacing the vulgar step by which one reaches a raised alcove elsewhere… Finally in the useless, if not unusable, air that everything takes on here, which is undoubtedly the supreme degree of luxury…”. [17]

Unable to allow such a hostile article to pass, Guimard had a reply published in the supplement of the magazine in February 1904. While reproaching De Félice for not doing his job as an art critic, he justified the term “Architect d’art” by its Greek etymology (archos, chief and tecton, worker), reserving the right to add the mention “d’Art” which he considered justified in the light of banal and unartistic constructions produced by professionals entitled “Architects”. Still in his response to De Félice, to define the “Guimard Style”, he reiterated the formulas he had already placed in his little manifesto printed on the packaging of his postcards and on the back of the invitation to his conference at the Grand Palais: “satisfy everyone’s programme, use modern resources, take advantage of the progress of science applied to all branches of human activity, express the character of matter”, which he summed up once again in his trilogy “logic, harmony and feeling”. However, this programme, which reflects the rationalist side of his creation, lacks the unbridled decorative inventiveness that most critics and the public rejected at the time and which is so attractive to us now. In fact, he will never want to explain himself on this dreamlike and fantastic side of the “Guimard Style”, no doubt considering it to be a take-it-or-leave-it proposition.

Curiously, such a badly started relationship between the two men found a rather happy ending in the article De Félice devoted again to the 1904 Salon d’Automne. With much less irony, he then commented favourably on Guimard’s consignment of three sets of furniture:

“[…] for M. Guimard himself, the art architect, seems this time to be timidly sacrificing to simplicity and reason. […]”[18]

A few years later, in 1907, Guimard presented at the exhibition of the Société des Artistes Décorateurs a very large stand including a large number of his ornamental cast iron pieces in Saint-Dizier. In his report published in the magazine Art et Décoration, Paul Cornu made the same reproaches as in 1903 about the expression “Guimard Style” which certainly accompanied the stand:

“M. Guimard thinks he has created a style. He even gave it his name. In reality, he has only created a formula, but submits all the materials to it. Iron, cast iron, bronze, wood, staff, stoneware, stained glass, fabrics, in turn translate his inextinguishable thirst for decoration.”[19]

Fortunately, within more confidential or professional journals, some authors have been much more lenient about the legitimacy of the expression “Guimard Style”. This is the case of Royaumont[20] in his account of the same salon of the Société des Artistes Décorateurs in 1907, published in the Revue Illustrée. While noting that Guimard influenced his style by revisiting those of past centuries, he admits that this very recognizable creation, extending to all fields, cannot be described in any other way:

“[…] but the most complete part is the fragment of the dining room, the whole of which proves that modern art has been able to benefit from the works of the past and that it can, in skilful hands, continue the tradition. And all this, however, with such a personality of touch, that one could not find to define these forms of any other name than Guimard style!”[21]

Commenting again on the same exhibition, the Journal de la Marbrerie et de l’Art Décoratif, in three issues, gave one of the few really enthusiastic articles[22] on Guimard’s work in general and on his exhibition in particular; so enthusiastic, moreover, that one wonders whether the architect might not have held the pen of the anonymous journalist. He justifies in passing the legitimacy of the expression “Guimard style”:

“The qualities of this work, in which the most exact logic unites with the most sensitive distinction, shows to what extent the appellation Style Guimard given to the works of this artist is justified.”

Inflexible, Guimard persisted in using the term “Guimard Style” over the following years. It appeared, as mentioned above, on signs displayed on the stands of the exhibitions and fairs in which he participated, but also more concretely on certain works themselves, such as the commercial prints of some of his ornamental fonts. Thus, around 1912, new models of cast iron bench legs (GO and GN) were designed with the words “Guimard Style” engraved in a highly visible recess. The Gb coffin handle, also marked “Guimard Style”, may have been designed after the First World War, as may the designs for mass produced graves, one of which was marked “Tombeau d’Art/Style Guimard” (i.e. artistic grave/ Guimard style)

GN bench leg with the inscription “Style Guimard” in hollow. Reserves of the Saint-Dizier foundry (currently assigned to the collections of the Saint-Dizier museum). Photo author.

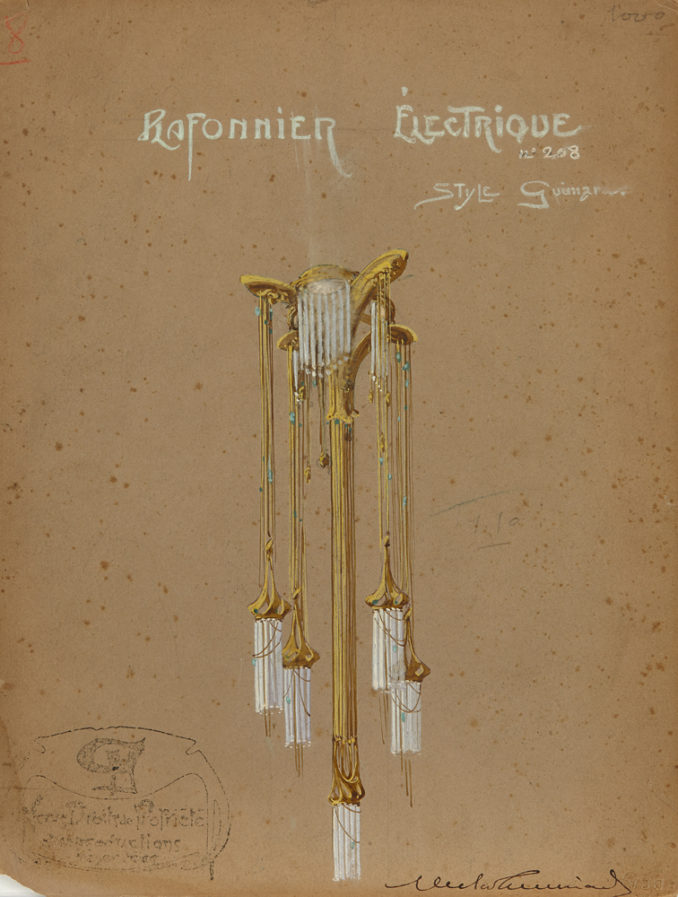

The serial production of objects for the architectural décor has mobilised a great deal of creative energy on Guimard’s part. Produced in collaboration with industrialists or workshops, these editions were an opportunity to publish specific catalogues in which the existence of the “Style Guimard” was mentioned as much as possible. We will examine the particular case of the ornamental cast iron catalogues below, but each plate in the catalogue of his Lustres Lumière (i.e. Lumière Chandeliers), published before 1914, received the mention “Style Guimard”. The same applies to the gouache drawings of the chandeliers we know.

Project for a Guimard style electric ceiling light. Gouache on strong paper. Private collection. Former Yves Plantin collection. Photo Art Auction, 2015.

The draft agreement drawn up in November 1908 by carpet manufacturer Aubert also provided for the filing of the drawings supplied to the Commercial Court under the heading “Style Guimard”. We have no information on the other catalogue projects that Guimard seems to have considered (mirrors, vases, cutlery and probably tombs) but for furniture, the contract he signed in 1913 with the manufacturers of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine Olivier and Desbordes did stipulate that the designs would be registered under the name “Style Guimard” and that a special catalogue bearing the words “Style Guimard” would be printed in 3000 copies at the expense of Olivier-Desbordes.

The last known instance of the architect’s participation in a commercial catalogue is the “Lambris Guimard” which appeared in the 1926 Elo catalogue. This company had specialised in publishing fibro-cement wall decorations, a material in which Guimard became interested late in life, notably for the town hall of the French Village at the 1925 Exhibition of Decorative Arts.

It seems that Guimard’s perseverance finally had some results and brought the expression “Style Guimard” into the language of the time, at least in Paris. But for there to be a popularisation of an expression which concerns the artistic field, it was necessary for it to be taken up and propagated by the non-specialised press. Such an example is offered to us by the article by an anonymous author who wrote about the great works in Paris in La Politique Coloniale of September 7, 1903 and who gives his opinion on one of the recurring debates of the time: whether or not to maintain the Eiffel Tower. He spoke out against its destruction but, he continued, if something were to happen to it, he would like it “to be rebuilt elsewhere, in the Guimard style, the only architect to have made real use of ornamentation with iron up to that time”…

In this quest for recognition, Guimard was undoubtedly assisted by a friendly and literary circle of early followers such as Georges Bans, Fernand Hauser, Émile Straus or Stanislas Ferrand. Another fervent supporter of the architect, the poet and art critic Alcanter de Brahm[23] was a great admirer of Guimard’s ideas. He frequently used the expression “Style Guimard” when he wrote about architecture and the decorative arts, notably in the magazine La Critique, of which he was one of the main editors, but also in larger-circulation dailies such as le XIXème siècle or Le Rappel, contributing in his own way to the popularisation of the expression. Always in touch with this friendly circle, La Critique thus delivered an anecdote which takes place during the party offered by Guimard at the beginning of 1909 on the occasion of his engagement. The journalist and poet Fernand Hauser spoke about the “growing popularity” of the “innovative art forms” defended by Guimard and recounted a personal anecdote in these words:

“It’s the next glory that’s on the horizon. I witnessed it the other day in one of our department stores when a customer, on the occasion of a Christmas gift, was selling an art object, and the clerk selling her this article added: “It’s what we do best currently, it’s the Style Guimard. »[24]

In this particular case, the article in question was probably not an object created by Guimard and it would therefore already be a shift in meaning that globalized the production of Art Nouveau style decorative art under the name of Guimard.

Another poet, largely passed on to posterity, showed less discernment concerning Guimard than the previous ones, which remained more obscure. Guillaume Apollinaire, since it is he who is referred to, had a fairly extensive career as an art critic in the press. Being in daily contact with the most modern artists – painters in particular – he was much less sensitive to decorative art and architecture. In L’Intransigeant he used the expression “Style Guimard” to comment on the architect’s submissions to the salons of the Société des Artistes Décorateurs. But with his cold writing and an almost jaded tone, he suggests that his works leave him speechless, even if quoting from his works seems to be a must. In 1911 first of all, ignoring the architect’s stylistic evolution, he evokes without nuancing it the stylistic kinship with the metro:

“M. Guimard exhibited photographs of the house he designed, furniture, jewellery and other small objects. Nothing to say about it. It’s the Guimard style and you know the Metro.”[25]

Then again in 1913, with the same ambiguity but this time in the past tense:

“M. Guimard was so much influenced by what has been called the Guimard style that his plans and photographs of buildings cannot be ignored.”[26]

- “Style Moderne”

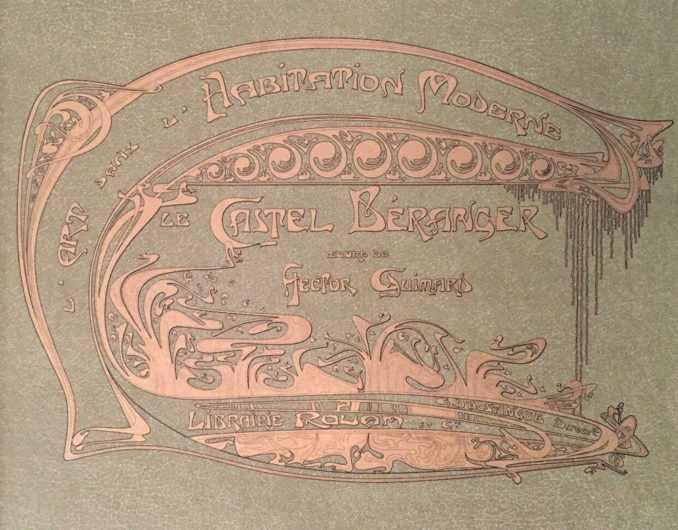

The appearance of the mention “Style Modern” is more difficult to spot. Being less controversial, it has not been the subject of acrimonious lines towards Guimard in the press. The word “modern” is also found in practically all of Guimard’s theoretical writings from the beginning of his conversion to Art Nouveau, since the portfolio he devoted to the Castel Béranger is entitled: L’Art dans l’Habitation Moderne (Art in the Modern Home) and we saw it used in 1897 alongside “national”.

Cover of a fac-similé of the Castel Béranger portfolio. Private collection.

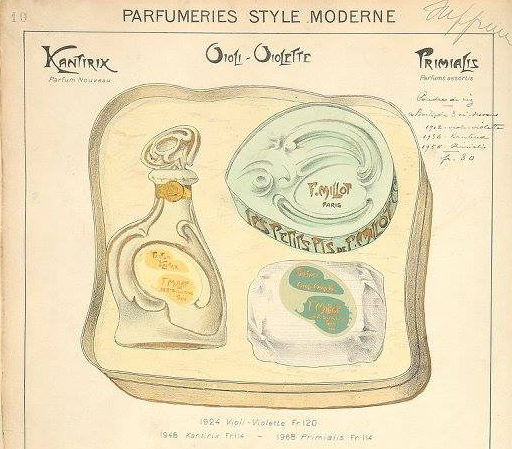

At the 1900 Universal Exhibition, Guimard created a remarkable stand for the perfumer Millot. With a view to a homogeneous presentation, in addition to the decor and furniture, he was also commissioned to create models of bottles and boxes for the launch of several new perfumes and their derivatives. These models were included in the perfumer’s commercial catalogue, in the form of coloured drawings with the names of the perfumes and the company name “F. Millot” calligraphied by Guimard, without his name appearing. The heading of these three pages is “PARFUMERIES STYLE MODERNE”, a mention which is not repeated on the other pages of the catalogue.

Millot commercial catalogue , pl. 10 (detail), without date, c. 1905. Private collection.

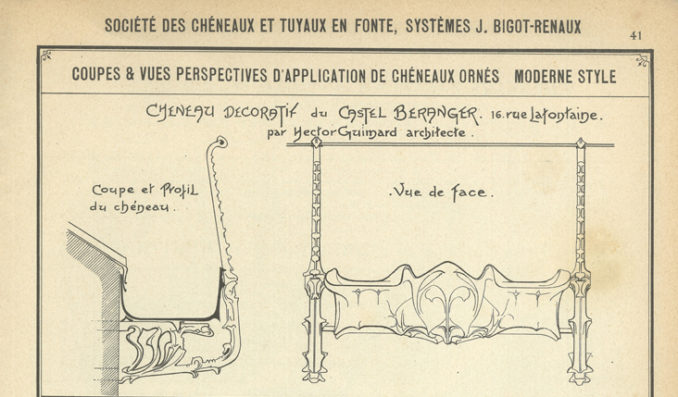

The word “modern” immediately brings to mind “Modern Style”[27], one of the expressions used to designate the Art Nouveau style. As much as ours, the 1900’s was a time of Anglicism. However, they could also be used with a slightly pejorative meaning. This is sometimes the case with “Modern Style”, which was not an English import term, but which may have been used with the intention of denouncing once again the real or supposed foreign origins of Art Nouveau. However, this term quickly became part of everyday language and is found, in the francized form of “Moderne Style”, in another commercial catalogue published in 1902, which includes models by Guimard. This was the catalogue of the foundryman Bigot-Renaux, specialising in gutters, which Guimard frequently used from Castel Béranger. This Meuse-based company published several of his models for fitting his buildings, as well as the pavilions and kiosks of the metro. It should nevertheless be noted that, for this catalogue, Guimard probably did not have the mastery of the mentions used in the header of the plate.

Bigot-Renaux commercial Catalogue 1902 (detail) Private collection.

It was around 1906-1910 that the adjective “modern” came back more insistently. Guimard then planned to build a series of investment properties financed by the “Société Générale de Constructions Modernes” (formed in July 1910), in which he was a stakeholder, along with his father-in-law and Léon Nozal. This project included a new street to be subdivided, which he intended to name “rue Moderne”[28]. It was opened under this name in 1911 and became rue Agar[29] the following year, but this did not prevent Guimard from keeping the name “Rue Moderne” in the plans reproduced in the article in the supplement to the magazine La Construction Moderne of 9 February 1913.

After the First World War, the adjective “modern” was shared by more and more designers who were preparing the 1925 exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts. It was also with this in mind that the “Group of Modern Architects” [30]was founded, of which Guimard became vice-president in 1923.

- « Style Guimard » or « Style Moderne », the example of the cast iron catalogues published in Saint-Dizier.

The catalogues of cast iron models created by Guimard and published at the Saint-Dizier foundry from 1908 onwards provide an illuminating example of the use of the terms “Style Guimard” and “Style Moderne”. Before our research in 2015[31] on this subject, it had not been noticed that in reality two types of catalogues had been published.

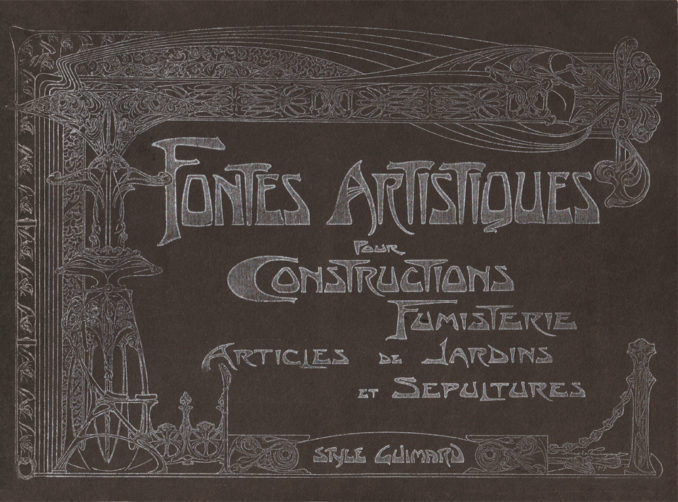

One of the two types of catalogues bears on its cover the mention in lettering designed by Guimard “Artistic fonts/for/constructions/fumistry/garden art/graves” and in a cartouche at the bottom, the mention “Style Guimard”. There is therefore no mention on the cover of the font of the name of the foundry which produced these fonts. On the inside of each plate, the words “Style H Guimard “, are printed on the upper part of each plate, placed below the name of the category of models presented. It is only on the lower part of the plates that one can find the discreet mention “Modèle de la Société F. S. D” which indicates, in a way that is not clear to the uninitiated, the Fonderie de Saint-Dizier. Due to the large number of references to the name Guimard, we refer to this type of catalogue as “Guimard Style”.

Cover of a “Style Guimard” catalogue. Private collection.

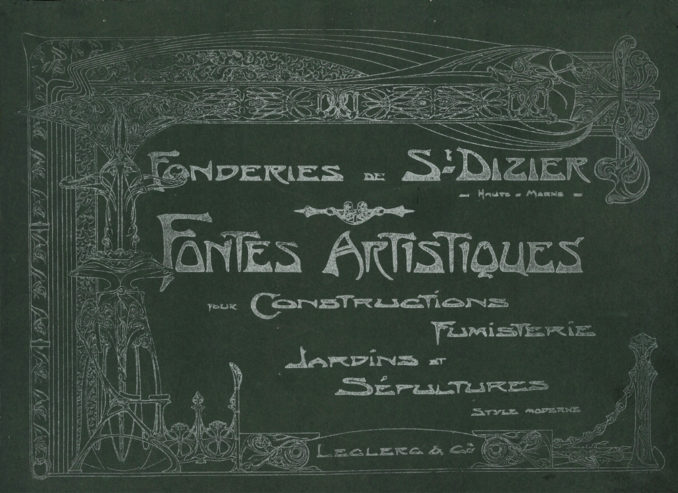

The other type of catalogue bears on its cover the mention in lettering designed by Guimard: “Artistic fonts for/Constructions/Fumistry/Gardens/Gardens/Tombs/Modern style”. The inscriptions were designed in a completely different way from those on the cover of the first type of catalogue. The letters are smaller and finer because it was necessary to make room for a sur-title “Fonderies de Saint-Dizier/— Haute-Marne —” separated from the main title by the drawing of a font playing the role of a net. In the cartouche at the bottom of the title, this time the words “Leclerc et Cie” (Leclerc and Co.) appear, which was the commercial name of the foundry at the time.

Cover of a “Style Moderne” catalogue. Private collection.

On each plate a heading mentions “Société des fonderies de St-Dizier (Haute-Marne) /Leclerc & Cie“.

Heading of the plates of the “Modern Style” catalogues. The font used for the top line is part of the family of fonts created by Georges Auriol. Private collection.

Each plate also bares the mention “Style Moderne”, placed below the name of the category of models presented, but one would look in vain for the name of the architect. To give a counterpart to the “Style Guimard” catalogue we therefore refer to this type of catalogue as “Style Moderne”.

Apart from the differences indicated, these two types of font catalogues have the same contents and will have the same increases in pagination from 1908 to about 1920. We conclude that they are parallel and not successive editions. The “Style Guimard” catalogue would be one of the many “Style Guimard” catalogues envisaged and would therefore be for the personal use of the architect. The other edition, the “Style Moderne” catalogue, more in line with commercial requirements, would be intended for use by the foundry.

Although it was used more often in the decade before the First World War, “Style Moderne” did not supplant “Style Guimard” as previously thought. It was simply used when greater discretion was sought. It was also undoubtedly an attempt to catch up with a concept of modernity that was increasingly eluding Guimard to blossom elsewhere and with others.

- Posterity

Of the two expressions, however, it is indeed “Style Guimard” that persisted after the First World War. It would be too tedious to list the articles that used it after this break, but we have seen it used regularly until the Second World War alongside other expressions such as “1900 Style” or “Style Metro”.

In 1921, when the campaign of the marble masons to equip French municipalities with memorials to the dead of 14-18 did not falter, the Marbreries générales, directed by Urbain Gourdon, sent interested municipalities a sample of their catalogue. Two architects’ recommendations were attached to this mailing: one by Jean Boussard (1844-1923), the other by Guimard, presented as “the famous architect who created the style that bears his name”[32].

In the following years, in the midst of the blossoming of the style soon to be called “Art Deco” (in reference to the Exposition des Arts décoratifs et industriels modernes of 1925) the tone was often mocking to evoke the decorative art of the beginning of the century. However, some journalists, more clairvoyant than others, noted as early as 1925 that the “Style Guimard” had made such an impression that the expression was on the verge of being passed on to posterity. Thus the newspaper L’oeuvre féminine of 8 July 1925, in an article on the exhibition of the renovators of applied art at the Galliera Museum, observed that some of these artists “still alive, happier than all the others, are today witnessing the triumph of their common cause: that of the architect Hector Guimard, for example, who, with his considerable fortune, left his name to a style”.

The use of the expression finally evolved in the 1930s when some authorities became aware of the need to protect a few representative samples of works from the beginning of the century. “Style Guimard” then became one of the “official” formulas to designate this period.

A few years later, the expression began to be recognised across the Atlantic. Alfred Barr himself, the brilliant first director of the MOMA in New York, aware of the specificity of Guimard’s plastic language, exchanged ideas with the widow of the architect, who had died some time before, certainly with a view to a donation. In a letter addressed to Adeline Oppenheim Guimard, he wrote: “these pieces should be particularly significant of the Guimard Style” then, citing a handle of an umbrellas as an example, he described it as: “an excellent example of the Guimard’s Style at its best and purest”[33], summing up in a few words all the strength of the style invented by Guimard.

The post-World War II period was ruthless for Art Nouveau. In a context of well-established certainties and almost sheepish intolerance, a whole panoply of human artistic genius was engulfed for two to three decades. Although the story of its rediscovery goes far beyond the subject of our article, it should be noted that the expression “Style Guimard” did not reappear so easily. It has competed with the names we mentioned above (“Style 1900” or “Style Métro”), other scornful ones like “Style Noodle” and even such a ridiculous name as “Style Jules Verne” proposed by auctioneer Maurice Rheims, without much success. The names of other emblematic artists of this style, such as the Nancy artists Gallé or Majorelle, whose production volumes placed them at the forefront of the art market, were also readily used to characterise it.

- Conclusion

This study devoted to the qualifiers applied by Guimard to his work may seem anecdotal at first, but it is revealing of several of Guimard’s character traits and how they interacted with his environment and the development of his career. The flexibility with which he adopted this or that qualification shows that he constantly reflected on the perception and acceptance that the public might have of his work. But the repeated choice of the term “Style Guimard” shows how much the architect wanted to “stand out” and obtain the recognition and social advancement that the usual channels of the academic curriculum had not provided. By disregarding the conventions of the time, he did not hesitate to be as disturbing for the formal side of his creation as for the way he qualified it.

These expressions, however, offered a convenient angle of attack to all those who only wanted to see the formal strangeness or virtuosity of this creation and who, without seeking to understand Guimard’s creative approach, which was based more on the properties of materials and the translation of forces contributing to the structure of objects and architecture, wanted to make people believe that the same tormented aspect could take on all kinds of products, whatever their size, materials or functions.

Frédéric Descouturelle and Olivier Pons

Translation Alan Bryden

[1] Siegfried Bing (Hamburg, 1838 – Vaucresson 1905) was an art dealer initially specialising in the arts of the Far East, collector, art critic and editor of the magazine Le Japon artistique.

[2] “It all smells like a vicious Englishman, a morphine-addicted Jew or a crafty Belgian, or a pleasant mix of these three poisons!” Alexandre, Arsène, Le Figaro, 28 December 1895.

[3] Boileau, Louis-Charles, L’Architecture, 19 December 1896.

[4] In contrast to those frequently used by Horta to dress some of its interior decorations.

[5] The National Exhibition of Ceramics and all the Arts of Fire was held at the Palace of Fine Arts on the Champ-de-Mars from 15 May to 31 July 1897 and was extended until 5 September.

[6] Eugène-Auguste Chevassus (1863-1931) known as Eugène Belville, painter, decorator and art critic. He became director of the magazine l’Art Décoratif in 1907.

[7] Its existence is mentioned in a short paragraph published in Le Moniteur des Arts of May 12, 1899.

[8] Adeline Oppenheim papers, The Public Library of New-York.

[9] Drawing GP 552 and GP 559, Guimard collection, Musée d’Orsay.

[10] Georges Léopold Cochet (1872-1962) known as Pascal Forthuny, writer, art critic and musician.

[11] Forthuny, Pascal, “Le Meuble à l’Exposition”, Le Mois littéraire et pittoresque, December 1900, p. 701-704.

[12] Vikado is a dark wood imported from South America which was used by many French cabinetmakers between 1900 and 1914.

[13] Vigne, Georges, Hector Guimard, Editions Charles Moreau, 2003, p. 111.

[14] La Vie Moderne, 1st semester 1901.

[15] Guimard, Hector, “La Renaissance de l’art dans l’architecture moderne”, Le Moniteur des Arts, 7 July 1899.

[16] Although La Fronde is known to be entirely administered and written by women, La Dame D. Voilée is one of the pen names of Charles-Antoine Fournier (1835-1909), a writer, art critic and collector who more usually signed Jean Dolent. For the record, this pseudonym is a (thinly veiled) allusion to an episode in the Dreyfus Affair, in late 1897, during which a mysterious veiled lady is said to have given Esterhazy (the real spy in the service of Germany) a damning document for Dreyfus. The Dreyfusard cartoonists then took great pleasure in depicting the veiled lady in question with the trousers and spurs of a cavalry officer.

[17] De Felice, Roger, “L’Art appliqué au Salon d’Automne”, L’Art Décoratif, December 1903, p. 234.

[18] De Felice, Roger, “L’Art appliqué au Salon d’Automne”, L’Art Décoratif, December 1904, p. 134.

[19] Cornu, Paul, “L’Exposition des Artistes Décorateurs”, Art et Décoration, 1907, p. 200.

[20] Louis-Étienne Baudier known as Baudier de Royaumont (1854-1918) was a journalist, editor, novel writer and historian. He was the first curator of the Maison de Balzac.

[21] Royaumont, “Art et Décoration”, Revue Illustrée, 1907, p. 775.

[22] “Le Salon des Artistes Décorateurs au Musée des arts décoratifs/L’Art moderne”, Journal de la Marbrerie et de l’Art décoratif, supplement to n° 101 of 5 January 1908 of the Revue Générale de la Construction.

[23] Marcel Bernhardt known as Alcanter de Brahm (1868-1942) was a writer, poet and art critic and became assistant curator of the Carnavalet Museum. He is known in particular for having revived the point of irony (he is not the inventor, as has been read here and there, this merit going to Marcellin Jobard, owner of the Courrier Belge, who first used it in the early 1840s). We will soon be publishing an article on La Critique et Guimard, a subject on which some charming nonsense with a mystical-esoteric tone has been read.

[24] La Critique, February 1909.

[25] L’Intransigeant of 25/02/1911.

[26] L’Intransigeant of 28/02/1913.

[27] The press also writes “le style Modern”.

[28] Plans of the projects conserved at the Cooper-Hewity museum, New York. On the plan of the first project of 1906, the street is simply referred to as “New Street”. In November 1909, the developer’s name was the “Société Immobilière de la rue Moderne” and, on the plans, the street to be created was actually named “Rue Moderne”. In April 1911, when the buildings were built, the plans still refer to a “Rue Moderne”. It should be noted that there was already an “Avenue Moderne” in the 19th arrondissement, which was in fact a small private street about twenty metres long, open since 1903, as well as a “Villa Moderne” in the 14th arrondissement.

[29] La Construction Moderne, 10 November 1912; Dictionnaire historique des rues de Paris, p. 68. The street takes its name from thestage name of the actress Léonide Charvin who lived in the adjoining house to the right of the Hotel Mezzara.

[30] Composed largely of former students of Charles Genuys, Hector Guimard’s teacher at the National School of Decorative Arts, the Group of Modern Architects had as a project the construction of a large hotel for travellers for the 1925 exhibition, before being entrusted with the creation of the French Village. Guimard built the town hall as well as a tomb and a small chapel in the cemetery adjoining the village.

[31] Descouturelle, Frédéric, Les Fontes ornementales de l’architecte Hector Guimard produites à la fonderie de Saint-Dizier, Master II thesis, EPHE, under the direction of Jean-François Belhoste, 2015.

[32] The marble mason was based at 33 rue Poussin, in the Auteuil district of Paris, close to the two architects, who were themselves a stone’s throw away from each other (41 rue Ribéra and 122 avenue Mozart).

[33] Papiers Adeline Oppenheim, The Public Library of New-York.