Hector Guimard’s participation in the 1925 Exhibition of Decorative Arts– Part 2

23 September 2025

After discussing the interiors of the town hall through its fixed decor, we continue our presentation with a look at its furniture. We will then turn our attention to the French Village cemetery, for which Guimard designed two funerary monuments. This is an opportunity to highlight the small chapel, a unique work that has long escaped the attention of researchers. Finally, we will conclude this study by discussing the reuse of a remnant of the town hall, which itself served as inspiration for the construction of another town hall a few years later.

The town hall furniture

Fifteen years ago, the discovery of a pair of chairs identical to those that furnished the town hall was the starting point for our research into this furniture and its supplier, EAGLE, a furniture manufacturer based in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine district of Paris[1].

Chairs of the town hall of the French Village oak, leather cover and modern nails; Private collection.

The appearance of a new piece of furniture by Guimard is always a small event in itself. While a new piece naturally enriches the reasoned catalogue of the architect’s furniture (currently in progress), it is also the best way to train our eyes and broaden our minds to furniture that we would not necessarily have associated with Guimard a few years ago. These chairs are a good example.

With a fairly simple overall design, they feature two distinct parts: a simple, unadorned seat contrasts seamlessly with a curved backrest that showcases the bulk of the cabinetmaking work. The only sculptural elements on the lower part are fine grooves that highlight the front legs along their entire height. The more complex design of the backrest leaves no doubt as to its creator: the ribbing and stretching of the material, the pointed “ears,” and the notched upper crossbar all refer to Guimard’s style.

These chairs are similar to a model of armchair, a photo of which can be found in the collection donated by the architect’s widow to the library of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. It was probably intended for the Nozal-Pezieux family, as a coat of arms clearly bearing the stylized initials NP adorns the upper crossbar of the backrest. This feature is also found on the chairs in the town hall, where there is an identical space for the initials.

Armchair with the crest Nozal-Pézieux, Bibliothèque des Art décoratifs, donation by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulmes

For EAGLE, participating in an event such as the 1925 Exposition required a significant investment, but one that was ultimately quite reasonable given the foreseeable economic benefits and expected gains in terms of image. Clearly, the company had no shortage of resources, having taken over an entire building in the heart of Faubourg Saint-Antoine. This high local visibility was reinforced by major, regular advertising campaigns in several national daily newspapers and specialist magazines.

By partnering with Guimard and supplying furniture for one of the main buildings in the French Village, the brand may also have wanted to benefit from the architect’s reputation. Although we do not know how Guimard came into contact with this company, he was undoubtedly impressed by the quality arguments put forward and detailed in the brand’s catalogs. These catalogs explain that “the furniture was manufactured in large quantities in two factories in Vincennes, while preserving the artistic aspect of its manufacture,” then finished in Paris “by master craftsmen in workshops adjacent to the stores on the Faubourg Saint-Antoine.”[3]

Deprived of his workshops since World War I, Guimard had to find a low-cost supplier who was nevertheless capable of producing (or reproducing) high-quality furniture. The architect already had connections in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, as a contract with one of its manufacturers had almost been signed before the war[4]. He therefore naturally turned to this neighborhood, where supply was still abundant.

Commercial flyer of the EAGLE company.

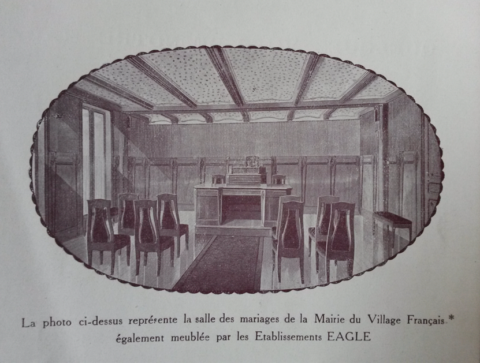

The photo of the wedding hall shows the mayor’s desk surrounded by two chairs, probably intended for the deputy mayors, while a third seat, perhaps an armchair, raised and decorated with a medallion, seems perfectly suited to accommodate the mayor.

The Mayor’s desk. GrandPalaisRmnPhoto. All rights reserved.

The stylized letters “R” and “F” on the upper band recall the official function of the premises. They brighten up a structure with massive, geometric lines, softened only slightly by the slanted corner motifs, which echo the design of the ELO paneling and reinforce the unity of the decor according to a principle dear to Guimard. The architect did not usually employ such an angular, almost rustic style, even in the mid-1920s. The explanation certainly lies elsewhere, as the main feature of this office was its modularity.

A detailed examination of the photo reveals that the office was in fact a set of independent pieces of furniture placed on a platform. Apart from the three chairs, which were by definition movable, it consisted of a large rectangular desk that could be used by the mayor for day-to-day administrative tasks and a recessed lectern, itself placed on another small platform intended for the mayor’s chair. This second part could certainly be used independently of the rest, for example for a speech. The complete configuration as it appears in the photo would therefore correspond to a situation in which the mayor would preside over a city council meeting alongside his two deputies.

Unable to afford a more refined set, Guimard opted for simple, functional furniture that could be easily adapted to life in a city hall.

The lack of photos of the other areas of the town hall or drawings of its furniture means that we do not yet know the exact size and location of this furniture, although we assume it to be fairly modest. However, we have found some answers in the advertising campaign launched at the time by the EAGLE company and in its catalogs published at the same time.

The 1926 catalog reveals an artist’s impression of the town hall’s wedding hall. Although fanciful in some respects—the stained glass windows that occupied the entire left side wall, for example, have been replaced by separate windows—the illustration is precise enough that the chairs and the mayor’s desk are easily recognizable, as are the ELO paneling and speckled ceiling as they appear in photos of the time. The artist even took care to include the Lustre Lumière wall lights that adorned the four corners of the room.

Extract of the ELO catalogue, 1926. Collection BnF.

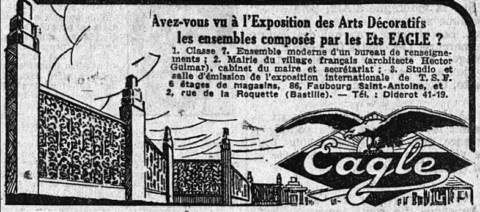

The presence of a bench on the right suggests that additional or complementary furniture was probably scattered throughout certain areas or rooms of the town hall. Advertisements published in the summer of 1925 also provide some clues as to the location of the furniture. L’Intransigeant of August 22, 1925, for example, invited readers to visit “the Decorative Arts Exhibition featuring ensembles designed by EAGLE,” including “the mayor’s office and secretariat in the French Village town hall (architect Hector Guimard).”

Logically, the rest of the furniture was therefore located in the secretariat, the other administrative room in the town hall. The ensemble must therefore have comprised no more than a dozen pieces of furniture divided between the mayor’s office and the secretariat, which could be broken down as follows: six or eight chairs, two armchairs, two desks, and perhaps a few side benches.

Advertisement for the EAGLE bran, L’Intransigeant, 22 August 1925. BnF/Gallica.

For both economic and stylistic reasons, Guimard drew on his earlier work, asking the EAGLE company to reproduce, in a simplified form, a chair model whose rather sober design, even for the 1900s, was compatible with the decor and architecture of the 1920s (at least that of his town hall). The mayor’s desk and lectern are therefore probably the only truly original creations in this set of furniture.

The French Village cemetery

For visitors to the French Village, the chances of bumping into a mayor in the corridors of the town hall were as slim as the risk of encountering a ghost or will-o’-the-wisp in its cemetery, since no one was buried there. However, it seems that the atmosphere of the place inspired a few vocations. An amusing anecdote published in the press recounts the arrival of a visitor at the general secretariat of the Exhibition, who, in all seriousness, requested a perpetual concession in the small cemetery…[4].

About ten days before the official inauguration of the French Village as a whole, the newspaper Excelsior reported on the inauguration of its cemetery on June 4, 1925, illustrating its article with a photo taken during the ceremony. Standing slightly behind the four officials, a fifth figure in profile, tall and thin, with a white beard, holds his hat in his left hand. Hector Guimard is easily recognizable, seemingly listening attentively to the comments of his companions for the day.

Inauguration of the cemetery of the French Village, Excelsior, 05 June 1925. BnF/Gallica.

Among the personalities present that day was the all-powerful president of the French granite producers’ union, Edmond Pachy, who had spared no effort to install a cemetery—a first for an installation of this scale at an international exhibition—which had inevitably sparked some comments in the press, at best amused, often skeptical of this commercial exercise, which was morbid and questionable to say the least… With considerable resources at his disposal, the source of which was easy to imagine in the aftermath of the First World War, Pachy had succeeded in mobilizing several major funeral companies around this project, as well as some big names in modern art.

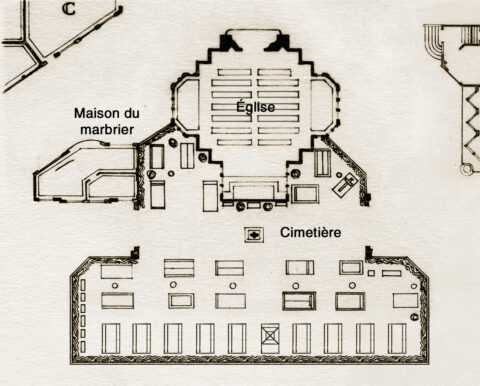

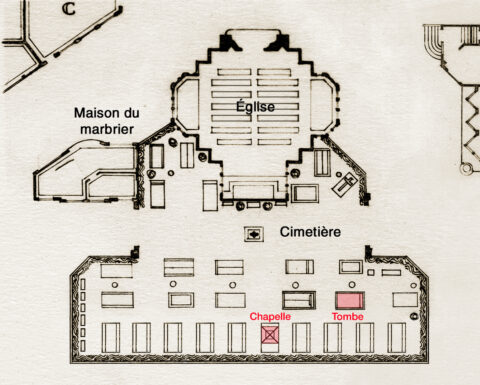

The cemetery occupied a small space at the foot of the church apse and, as was fitting, close to the home of the stonemason of architect Louis Brachet (1877-1968).

Partial plan of the French Village centered on the cemetery drawn according to the plans of the portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Rassemblés par Pierre Selmersheim, éditions Charles Moreau, 1926 and of our own research. Photomontage and drawing F. D.

Louis (Félix) Bigaux (1858-1933), who designed the cemetery, also created several tombs and, most notably, the bush-hammered granite entrance to the cemetery, which was crafted by the French Granite Producers’ Union and built by its members.

Entrance of the cemetery of the French Village by Bigaux. Portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Rassemblés par Pierre Selmersheim, éditions Charles Moreau, 1926, pl. 9. Private collection.

The cemetery contained around thirty funerary monuments, including a calvary and a chapel[5], all designed in a modern style. These included works by Bigaux, Roux-Spitz, Lambert, Dervaux, Victor Prouvé, the Martel brothers, and of course Guimard.

Funerary monument by the architect Roux-Spitz. La Construction moderne, 19 July 1925. Private collection.

The presence of two works by Guimard in the French Village cemetery could be perceived as post-war opportunism. This motivation is undoubtedly real, both for Guimard and for his colleagues involved in the cemetery, but it must also be put into context, bearing in mind that the construction of tombs was an integral part of the architect’s profession. When they had the means, after building their homes, families often entrusted their architects with the construction of their final resting places. However, this personalized activity tended to decline during the 20th century, as the bourgeoisie gradually turned to manufacturers offering standardized products. As far as Guimard is concerned, the fact that we have an increasingly comprehensive knowledge of his work means that we now have a fairly complete picture of his activity in the funerary field. He began very early on, and although his work seems significant to us, we do not yet know whether it was a particular interest of his or whether it was typical of his colleagues, among whom it is not so prominent. Nevertheless, we lean towards the former hypothesis, given the architect’s sustained and regular efforts in this field throughout his career. In any case, this activity reflects the evolution of his style, even if he sometimes had to compromise with the wishes of his clients.

His most famous (and undoubtedly most spectacular) tomb is that of the Caillat family at Père-Lachaise, but his work also included tombs, small chapels, and funerary or commemorative monuments.

Caillat grave at the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris. Photo author.

The Decorative Arts Library collection also contains a number of photographs of funerary monuments, which were probably intended for inclusion in a catalog.

Fake tomb incorporating a GA cross, two GB bouquet-bearing pilasters, two GB posts, a GF planter, mesh and chain links, c. 1910. Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs. Donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Another series of later photographs shows simplified, fake monuments photographed outdoors. We can assume that they were part of an exhibition or presentation at a funeral company. These examples show that, more than ever, even in the funeral sector, Guimard intended to distribute his work in to reach a clientele who could not afford a unique creation but wanted the graves of their deceased to have a modern artistic touch.

Fake tumb incorporating a GB cross and surround. Bibliothèque des Arts décoratifs. Donation by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Guimard drew heavily on his catalog of cast iron designs published by the Saint-Dizier foundry from 1908 onwards. Several plates relate to funerary ornamentation: pilasters and grave surrounds, crosses of all sizes, wreath holders, coffin handles, and chain links. Curiously enough, none of these items were included in the French Village cemetery. No doubt their style was considered too dated.

Guimard’s two new creations for the French Village cemetery thus complete the long list of works he devoted to this field[6].

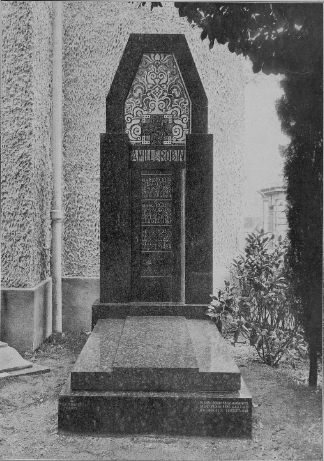

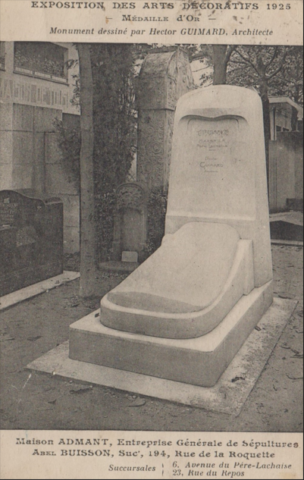

His involvement in the French Village cemetery is attested to by an early funerary monument that won a gold medal. An old postcard, published for promotional purposes by the tomb manufacturer Admant-Buissont, celebrated this award.

Funerary monument at the cemetery of the French Village. Ancient postcard. Private collection

Apart from perhaps the upper part of the stele, where a light sculpture frames the identification of the deceased (or a possible epitaph), almost nothing betrays the identity of its creator. The jury seems to have taken great pleasure in rewarding Guimard’s ability to simplify his style to the extreme, as this tomb is probably the simplest and most unadorned work of his entire career!

The background of the postcard illustration was a valuable source of information in locating the tomb within the cemetery and helping us to establish its layout. On the left, we can see the façade of the Maison de Tous, in the center behind Guimard’s tomb, the monument sculpted by Émile Derré (1867-1938), and even one of the three lava stone fountain terminals scattered throughout the French Village, which can be glimpsed behind the tree to the left of the tomb[7].

Guimard’s second creation for the French Village cemetery long escaped the attention of researchers, to the point that its existence was questioned. To our knowledge, no book or article entirely devoted to this section of the French Village has been published, so at first we had to make do with fragmentary and often imprecise information scattered throughout the press of the time.

The Official General Catalog does mention the presence of a chapel within the cemetery, but without providing any further information. The Hachette guide to the Exhibition is much more precise, detailing some of the works and their creators. We learn that “(…) Mr. Hector Guimard built a small chapel whose appearance highlights this architect’s very characteristic evolution towards less complicated forms, but always in perfect balance”[8].

In the literature devoted to Guimard, several hypotheses have been put forward, sometimes with supporting photographs, but without convincing readers[9].

Furthermore, none of the monuments related to the cemetery published in the press at the time or in public collections correspond to the definition of a funeral chapel[10].

This situation persisted until the discovery of new autochromes in the collections of the Albert Kahn Museum. In several photographs relating to the French Village cemetery and dated July 1, 1925, a tall, compact shape stands out against the light. Although the photo is dark, the overall composition of the building catches the trained eye and could correspond to the description of the Guimard chapel in the Hachette guide.

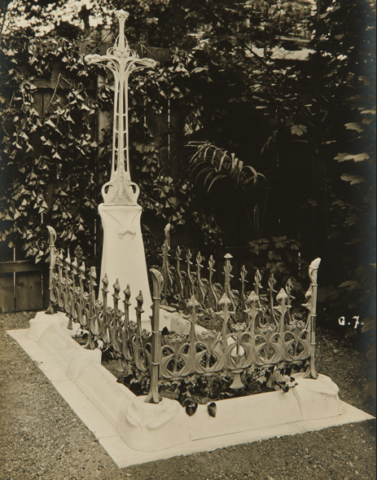

View of the cemetery of the French Village autochrome. Musée départemental Albert-Kahn, Département des Hauts-de-Seine.

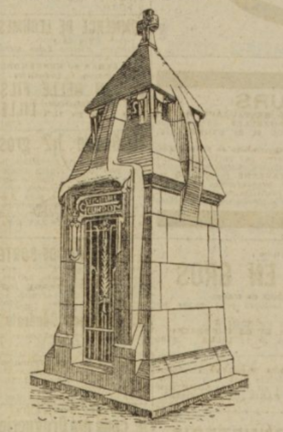

At the same time, Marbreries Générales Gourdon launched a major advertising campaign to promote a new model of funeral chapel on display at the “Modern Village Cemetery,” accompanied by an illustration[11]. Presented from a different angle, showing the main façade and its entrance closed by a wrought-iron door, the monument is easily recognizable with its uprights rising halfway up three of the four façades and enveloping an original double openwork roof system. The treatment of the entrance—whose masonry stands out clearly from the monument—is even more characteristic of Guimard’s work. From the upper lintel of its frame springs a fourth upright, which also joins the small capital crowning the chapel and supporting the cross at the top.

The chapel of the French Village. L’Écho du Nord de la France, 12 août 1925. BnF/Gallica.

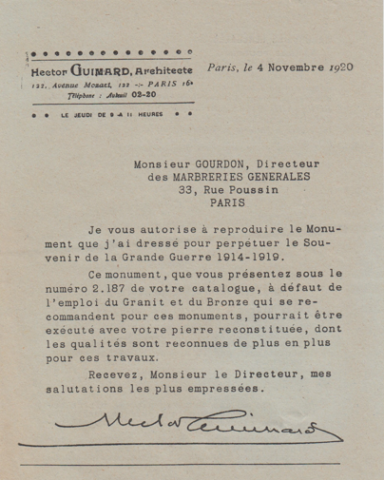

Curiously enough, but perhaps as a result of an agreement (or a dispute…), the advertisements do not mention Guimard, even though the company was well acquainted with the architect. In the aftermath of World War I, Marbreries Générales Gourdon sent out advertising leaflets and catalogs accompanied by a facsimile of a letter on the architect’s letterhead and signed by him.

Fac-similé of a letter by Guimard attached to the catalogues of the Marbreries Générales Gourdon.

Private collection

Thanks to these new discoveries, we have been able to finalize the cemetery map with the location of Guimard’s two monuments. We take this opportunity to launch a search for these two works, which were certainly located in the alleys of a (real) cemetery.

Map of the cemetery of the French Village drawn from the plans of the portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Rassemblés par Pierre Selmersheim, éditions Charles Moreau, 1926 and from our research. Photomontage and drawing F. D.

Remains and legacy

Some parts of the Exposition were quickly demolished after it closed, while others remained standing for several months for financial reasons, as no one wanted to bear the cost of demolition. Fortunately, a few works have survived to this day, sometimes on display in public spaces or added to private or museum collections.

The demolition of the French Village also took several months. It seems that the town hall was still standing in January 1926, as noted by several journalists who came to report on the demolition work. Guimard probably tried to offer the building to local authorities, but without much success, as far as we know, since the town hall did not survive the Exposition. However, it is entirely possible that some of the decorations and materials were reused elsewhere. Guimard himself reused at least one element, adapting it to a new configuration.

Main entrance door of the town hall of the French Village. Bibliothèque des Arts décoratifs. Donation Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

The entrance door of the building on Rue Henri Heine, built by Guimard, bears a striking resemblance to that of the town hall…

Entrance door to the building 18 rue Henri Heine, 75016 Paris. Photo author.

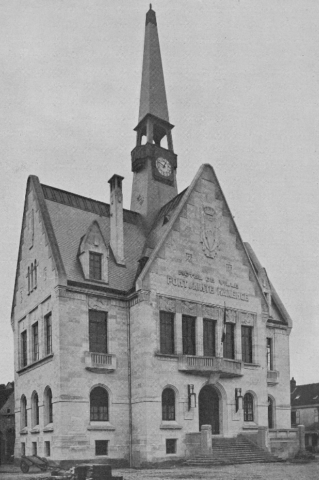

Although Guimard’s town hall did not enjoy a second life within a municipality, it nevertheless seems to have inspired the designers of the town hall in Pont-Sainte-Maxence (Oise), built in 1930. This hypothesis, put forward by Léna Lefranc-Cervo at the Hector Guimard study day organized last year at Paris City Hall, seems entirely convincing to us [12]. Triangular pediments on the facades, a spire set back from the pediment of the main facade, dormer windows on the roof… there are many similarities in the overall composition of the two buildings (and even in their interior layout). Furthermore, the fact that the three architects Marcel Jannin, Jean Pantinet, and Jean Szelechoivsk were members of the Society of Modern Architects (formerly the Group of Modern Architects founded by Guimard in 1923) also supports this assumption.

Town hall of Pont-Sainte-Maxence. La Construction Moderne, n°33, 18 mai 1930. Portail documentaire de la Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine.

However, the resemblance ends there, as the architects opted for a massive, angular building with no ornamental references to the Art Nouveau style.

Conclusion

Although Hector Guimard’s work in the aftermath of World War I did not receive the same attention as the first part of his career, it is nonetheless of real interest. The architect continued his work, charting his course with the same ideas while discreetly but significantly adapting them to the social context of his time. Resolutely committed to modern architecture and applied art, he always advocated the renewal of the decorative arts, a principle he put into practice by simplifying his style but at his own pace, cultivating his difference and repeating to anyone who would listen that fashion should not dictate art.

On April 9, 1930, at around 6:30 p.m., Hector Guimard sat down at the Eiffel Tower radio station for a short lecture on architecture and fashion. Explaining to listeners that “[…] the nature of fashion is to change rapidly. Architecture being by definition the art of building, which implies lasting works, the word ‘fashion’ is therefore a contradiction in terms in architecture,“ he denounced the austerity that he believed was rampant in architecture and the applied arts: ”I think, moreover, that the current fashion for the nude responds to a whole state of mind. We no longer believe in mystery; we want to immediately understand things that we can simply touch.”[13].

The gradual evolution of Guimard’s style was often misunderstood, with some observers of the time judging a little too quickly (even though they did not have all the explanations) that Guimard was stubbornly sticking to the 1900 style. But while the stylistic gap between him and his colleagues was still acceptable in the mid-1920s, it became untenable at the beginning of the following decade.

Olivier Pons

Notes

[1] Originally from the US, the brand specialized in mid- to high-end office furniture. Its arrival in France seemed fairly recent, as the first mentions of its existence date back to the early 1920s. The main store occupied a large space on Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Antoine, but EAGLE also had another store nearby on Rue de la Roquette and a branch in Lille.

[2] In addition to its presence at the French Village town hall, the brand exhibited in the information office section (class 7), for which it won a silver medal, as well as in the studio and broadcasting room of the International TSF Exhibition.

[3] EAGLE catalog from 1926. BnF collection.

[3] A draft contract between Guimard and the manufacturer Olivier et Desbordes, preserved in the Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard papers at the New York Public Library, provided for the small-scale production of “Guimard-style” furniture.

[4] Le Merle blanc of May 30, 1925 reports the visitor’s request: “Sir, I have come to ask you to grant me a perpetual concession at the cemetery of the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs. Of all the cemeteries, yours is my favorite. At Père-Lachaise, there are too many great men. The Montmartre cemetery is too close to the dance halls on the hill. Pantin and Bagneux are too far away for my friends. At the Passy cemetery, I would fear suffering the same tribulations as Marie Matskirsef [sic]. With your permission, I want to be buried in the Cours-la-Reine cemetery.”

[5] Official General Catalog. Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Posts and Telegraphs, 1925. Private collection.

[6] We have counted sixteen funerary and commemorative works, not including the drawings from the École nationale des beaux-arts and the unrealized project for a commemorative monument to the Victory of the Marne.

[7] L’Auvergne littéraire et artistique et félibréenne, July 1925. The students of the Volvic Departmental School had provided three lava stone drinking fountains. Two were located in the cemetery, while a third had been installed in the courtyard of the French Village school.

[8] Paris, arts décoratifs, 1925, Guide de l’Exposition, Librairie Hachette. Private collection.

[9] Georges Vigne, Hector Guimard, Éditions d’art Charles Moreau, 2003, p. 357. A photograph illustrating the article on the French Village cemetery is supposed to show Guimard’s chapel behind a sculpture by Théodore Rivière. This photo was actually taken at the Château de Nice cemetery. The sculpture representing the two sorrows is still in place and the chapel in the background is the funerary monument of a prominent Nice family.

[10] A funeral chapel is a monument that partly resembles a religious chapel but is less imposing. It is usually closed by a door and has a commemorative altar used for eulogies for the deceased. Coffins are either placed inside if the chapel is large enough, or underneath it (in the case of the Guimard chapel).

[11] La Dépèche (Toulouse), August 10, 1925; Le Grand écho du Nord de la France, August 12, 1925; L’Est républicain, August 11, 1925. The advertisement that appeared in the European edition of The New York Herald on October 7, 1925 provides some additional information. The chapel is built of granite from the quarries of Becon (Maine-et-Loire) and can be ordered for the sum of 56,000 francs (door and windows included).

[12] Hector Guimard study day organized at Paris City Hall on December 10, 2024, to mark the end of the Hector Guimard year.

[13] L’Ouest-Éclair, April 9, 1930. BnF/RetroNews.

Translation : Alan Bryden