Hector Guimard’s first trip to the United States – New York 1912

February 2023

While the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York[1] inaugurated an exhibition dedicated to Hector Guimard[2] at the end 2022, which will then moved to Chicago, we are publishing the first in a series of articles on the direct and indirect links between the architect and the United States. In this first article, we thought it appropriate to recount Guimard’s first contact with the United States in the spring of 1912.

Following the death of his father-in-law, American banker Edward Oppenheim, on November 23, 1911, in New York[3], Guimard traveled there in mid-March 1912 with his wife Adeline for a stay of about two months. It was therefore both a private trip and, as we shall see, a business trip. Guimard acted as vice-president of the Society of Decorative Artists, a role he did not hold anymore since several months[4]. It is true that presenting himself under this label gave him the legitimacy to raise certain subjects, even if it meant bending the truth slightly.

The story of this trip began very early on, as an article reported Guimard’s presence on the ocean liner taking him across the Atlantic. Although this first text may seem anecdotal, it reflects the architect’s state of mind as he embarked on his first trip to America. That is why we are offering the best passages from it.

The American press then reported several times on the professional meetings Hector had during this first stay. As the texts are sometimes redundant, we will not provide translations of all of them, but only the French version of the three accounts published in The New York Times on April 5, 1912, The Calumet on April 23, 1912—in which only the extracts directly related to Guimard are included—and The American Architect in May 1912. Finally, we will simply list the other newspapers that reported on the event.

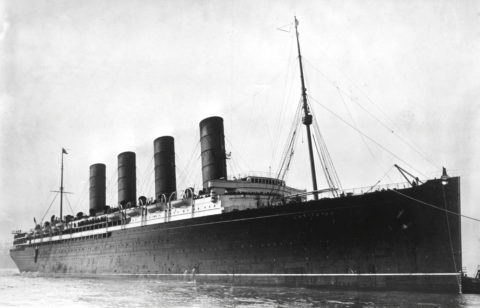

It should be noted that Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard is not mentioned in any of these articles. However, we assume that she was present during the interviews, as Guimard could not speak English[5]. Furthermore, thanks to a postcard sent in 1912 by Guimard to the staff of his offices on Avenue Mozart[6], we know that Hector traveled on one of the two transatlantic flagships of the English company Cunard, but without specifying whether it was the Mauretania or the Lusitania that welcomed him on board. The records of the Ellis Island Foundation and the newspaper article we are about to discuss tell us that it was the latter[7]: the Guimards boarded the Lusitania in Liverpool on March 9, 1912, bound for New York, which they reached on March 15, 1912.

The Cunard liner Lusitania. Source: Wikipedia

Aboard the ship, a chance encounter between a famous English illustrator and caricaturist, Harry Furniss (1854-1925, the author of the text), and his neighbor in the lounge, who was none other than “(…) the distinguished French architect, Mr. Hector Guimard (…)“, is the first known account of the architect’s trip to the United States[8]. Furniss specifies that this was Guimard’s first trip to America, the purpose of which was to study ”skyscrapers and other eccentricities of American architects.” Then, in a rather unfriendly tone, he indicates that Guimard “does not seem to like steel and brick skyscrapers,” even daring to ask the controversial question: “(…) he [Guimard] asks pathetically: why shouldn’t America have its own distinct architecture?” We will see that this reflection, which is one of Guimard’s major concerns about the ability of a country or city to develop a specific and harmonious architecture, will often come up again—albeit in a more diplomatic manner—during his subsequent speeches in New York.

Guimard sketched by Furniss aboard Lusitania. Coll. part.

No hard feelings, but undoubtedly inspired by this encounter, Furniss sketches Guimard, gently mocking the seasickness that seems to affect the architect: “(…) Guimard does not seem to like skyscrapers of steel and brick on land any more than he likes the skyscrapers of seawater that we encountered in the Atlantic (…)”.

Marie-Claude Paris then presents three articles on Guimard that appeared in the American press in chronological order, starting with The New York Times, followed by The Calumet, and finally The American Architect, before providing the original texts in English.

- GUIMARD’S COMMENTS IN AMERICAN NEWSPAPERS

I.1. The New York Times, April 5, 1912

In an article published in the New York Times under the headline “Artists Recall Their Stay at the Jullian Academy “[9], an anonymous journalist recounts a long and joyful commemorative gathering held at the Brevoort Hotel in South Manhattan on April 4, 1912[10]. The article mentions various artists who spent time in France and then became famous or held prominent positions in the art world or museums after returning to the United States.

Brevoort Hotel, Fifth Avenue and 8th Street, New York, New York, 1919. (Photo by William J. Roege/The New York Historical Society/Getty Images.

” Amidst this joyful and noisy crowd, the author notes a single solitary guest of honor, architect Hector Guimard, who, among other things, designed all the entrances to the Paris metro stations. In a brief speech, Hector mentions “the old-timers” and, in passing, America and Americans. “It goes straight to my heart to see old friends, all former students of Jullian, doing so well in your city. It is refreshing to see you show such interest in your student years in Paris. I have been charmed by this magnificent country and I will make only one comment that is not entirely complimentary: Americans are generally too modest.” This was the only speech of the evening, and after the guests were seated, the signal was given to begin the festivities.

I.2 The Calumet, Tuesday, April 23, 1912

In this article, Hector speaks in two capacities: as an architect and as vice president of the Society of Decorative Artists. His view becomes quite critical once again.

“Our architecture would be better appreciated if it had an American character and was not copied. I wondered if it is possible that the tall buildings you have here are pleasing to the eye and practical for housing their many occupants. I believe it is possible, but in my opinion, many examples of your skyscrapers are disappointing in that the idea of harmony[11] in a building has not been followed by the architect.

American architects should exchange ideas so that there is continuity and harmony in the succession of buildings they erect. Your architects show more strength and understand their work more deeply, I believe, than those in Germany or Great Britain, but my impression of New York is more that of a collection of buildings than of harmonious groupings as in Berlin or London.

Some American architects I have spoken to say that they have little latitude, that they have to build as the owner demands.

WHY DOES AMERICA NOT HAVE A SPECIFIC ARCHITECTURE? THERE IS A HUGE OPPORTUNITY. THERE IS NOTHING TO GAIN FROM COPYING OLD METHODS AND OLD MODELS. A DISTINCTIVE, TOTALLY NEW, SIMPLE STYLE, WITHOUT HARD LINES BUT YET STRONG FEATURES COULD EMERGE, ONE THAT WOULD BE RECOGNIZED AS AMERICAN.

Every European country is making this effort to EXPRESS ITSELF IN ITS OWN WAY IN ARCHITECTURE[13]. Germany has made an enormous effort in this direction, and this appears to visitors to Berlin to be largely successful.”

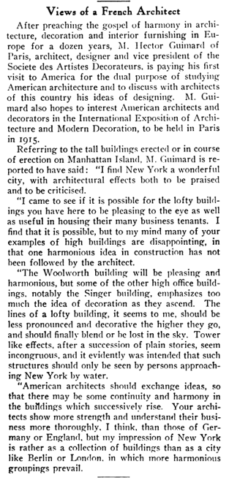

I.3 The American Architect, May 1912

Published at the end of his stay in New York, this last text appears to be a kind of conclusion: Guimard’s opinion on American architecture remains quite clear-cut, even though he takes care to nuance his remarks by citing specific examples of buildings. We also learn that his visit had another purpose: to interest his American counterparts in the future exhibition of modern art being prepared in Paris[14].

“After preaching the gospel of harmony in architecture, decoration, and interior design in Europe for twelve years, Mr. Hector Guimard of Paris, architect, designer, and vice president of the Society of Decorative Artists, is making his first visit to America with the dual purpose of studying American architecture and discussing his ideas on design with American architects. Mr. Guimard also hoped to interest architects and decorators in the International Exhibition of Modern Architecture and Decoration, to be held in Paris in 1915.

Regarding the tall buildings already erected or planned for Manhattan, Mr. Guimard reportedly said: “I find New York to be a magnificent city, with architectural effects that are both praiseworthy and worthy of criticism. I came to see if it is possible for the tall buildings you have here to be pleasing to the eye and also useful for housing their many tenants. It seems possible to me, but in my opinion many of your tall buildings are disappointing, in that the architect has not followed the idea of harmony in construction.

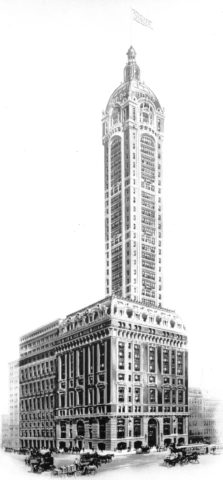

“The Woolworth building[15] will be pleasant and harmonious, but others, such as the Singer building[16] in particular, place too much emphasis on decoration in their upper sections. In my opinion, the lines of a tall building should be less pronounced and less decorative as they rise, eventually blending into or disappearing into the sky. After a series of unstylish floors, “tower” effects seem incongruous, and it is obvious that such structures should only be seen by those approaching New York by sea.

The Woolworth building c.1913. Source Wikimedia Commons.

The Singer building c.1910. Source Wikipédia.

American architects should exchange ideas so that there is continuity and harmony in the buildings that are being constructed one after the other. American architects show more strength and understand their work more deeply, I believe, than their German or English colleagues, but my impression of New York is more that of a collection of buildings than of cities such as Berlin or London, where more harmonious groupings dominate.”

- ORIGINAL TEXTS BY GUIMARD IN THE AMERICAN PRESS

II.1 Original text of part of the article in the New York Times “Artists hark back to days at Julian’s”

“There was one lone guest of honor. He was Hector Guimard, the distinguished French architect, who among other things designed all the subway stations in Paris. He is in America on business, and in a brief speech made some happy comments about the ‘anciens’ and incidentally, American and Americans.

“It delights my heart,” he said, “to find you old fellows, all of whom are Julian’s ‘anciens’, doing so well in this your great home city. It is refreshing to find you taking such an interest in the old student days in Paris. I have been charmed with this magnificent country, and I can make but one comment that could possibly be construed as not entirely complimentary, and that is that Americans as a rule are entirely too modest.“

II.2 Original text from Calumet

”Our architecture would show off better if it had an American distinctiveness and was not copied. By HECTOR GUIMARD of Paris. Vice President of the Society des Artistes Décorateurs.

I have wondered if it is possible for the lofty buildings you have here to be pleasing to the eye as well as useful in housing their many business tenants. I think that it is possible, but to my mind many of your examples of high buildings are DISAPPOINTING in that one HAS one HARMONIOUS idea in construction has not been followed by the architect.

American architects should exchange ideas so that there may be some continuity and harmony in the buildings which successively rise.

Your architects show MORE STRENGTH and understand their business more thoroughly, I think, than that of Germany or England, but my impression of New York is rather as a collection of buildings than as a city like Berlin or London, in which more harmonious groupings prevail.

Some American architects with whom I have talked say they have little latitude, that they must build as the owner directs.

WHY SHOULD AMERICA NOT HAVE A DISTINCTIVE ARCHITECTURE? THERE IS A GRAND OPPORTUNITY. LITTLE IS GAINED BY COPYING OLD METHODS AND MODELS. A DISTINCTIVE TYPE, THOROUGHLY UP TO DATE, SIMPLE, WITH NO HARD LINES AND YET STRONG, COULD BE EVOLVED WHICH WOULD BE RECOGNIZED AS AMERICAN.

Every European country is making this effort to EXPRESS ITSELF IN ITS OWN ARCHITECTURAL WAY. Germany has made a tremendous effort along this line, and that it has been largely successful is apparent to one who visits Berlin.

II.3 CPress clipping from The American Architect

Article published in The American Architect, mai 1912. Coll. part.

Beyond the four examples presented in this article, here is a (probably incomplete) list of other newspapers and magazines that reported on Guimard’s stay in the United States:

- The Daily Northwestern (April 2, 1912)

- The Indianapolis Star (April 7, 1912)

- Building Age (May 1912): “American Architecture as Seen by a Paris Architect”

- Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide (June 1, 1912): “American Architecture as Seen by a Paris Architect”

- The Concrete Age (June 1912): “French Architect’s Views on American Architecture”

III. SUMMARY

During his stay, Guimard’s opinion of New York architecture hardly changed, and upon leaving New York, the architect seemed as divided as he had been aboard Lusitania. In the Calumet and then the American Architect, he highlighted two fundamental flaws in skyscraper architecture: a lack of harmony and a lack of originality. As American architects were constrained by their clients, their art showed no distinctive features. It lacked vigor, harmony, specificity, and originality.

This judgment would be corroborated even more clearly twenty years later: on October 21, 1932, during a dinner with Louis Bigaux and Frantz Jourdain organized by Gaston Vuitton[17], Guimard echoed the following comparison regarding a building on the Champs Élysées constructed by the engineer Desbois: “What was said about the Eiffel Tower? It is, after all, a 300-meter monument that is less ugly than the first American skyscrapers.”[18].

Marie-Claude PARIS and Olivier PONS

Notes:

[1] The Cooper Hewitt Museum of decorative arts and design was founded in 1896 and opened to the public in 1897 thanks to Peter Cooper’s granddaughters, Eleanore Garnier Hewitt, Sarah Cooper Hewitt, and Amy Cooper Green. It was modeled after the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

[2] This exhibition will be held from November 18, 2022, to May 21, 2023, and then from June 22, 2023, to January 7, 2024, at the Richard H. Driehaus Museum in Chicago.

This exhibition on Guimard is not the first in the United States. For the record, the first major American exhibition took place in New York at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) from March 10 to May 10, 1970. It then moved to San Francisco at the Legion of Honor Museum from July 23 to August 30, then to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto from September 25 to November 9, 1970, and finally to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris from January 15 to April 11, 1971, where Guimard shared the spotlight with Horta and Van de Velde.

It was organized by F. Lanier Graham (assistant curator at MoMA), whom Adeline Guimard, then Hector’s widow, had met in New York, and above all thanks to the support of Alfred H. Barr Jr., the first director of MoMA, whom Adeline had contacted in 1945 and then met in Paris during her stay in June 1948.

In 1950, the Cooper-Hewitt Museum of Decorative Arts presented a few of Guimard’s works, then in 1951 the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon reassembled and presented Adeline’s bedroom at 122 Avenue Mozart in Paris.

[3] Edward Louis Oppenheim (born in Brussels on April 12, 1841) died of pneumonia in New York. An announcement of his death appeared in France in Le Matin on November 24, 1911. It is mentioned that E. Oppenheim was the father-in-law of Hector Guimard. At the time of his death, Edward was living with his daughter Nellie at the Netherland Hotel, 5th Avenue and 59th Street, New York. Renamed the Sherry Netherland in 1924, this hotel still exists at this address.

[4] Guimard was vice president of the Society of Decorative Artists in 1911, a role he shared with Paul Mezzara (1866-1918).

[5] According to American photographer Stan Ries, who took pictures of the Guimard Hotel in Paris.

[6] See Hervé Paul’s article entitled “Suzanne Richard, collaborator of Hector Guimard from 1911 to 1919” on the Cercle Guimard website (November 2021). Adeline Guimard painted a portrait of Suzanne Richard-Loilier, which she exhibited in 1922 at the Lewis & Simmons gallery, 22 Place Vendôme in Paris (portrait no. 28).

[7] The Lusitania was launched in June 1906 and made its maiden voyage in September 1907. It held the Atlantic blue ribbon for speed for two years before being dethroned by its sister ship, the Mauretania. During World War I, this ship was also used for transport and as a hospital ship before being torpedoed in May 1915 by a German submarine.

[8] Article published in Hearst’s Magazine, April 1912.

[9] This spelling is incorrect. The proper name “Julian” has only one “l.” The Académie Julian was founded in 1890 by French painter Rodolphe Julian (1839-1907). It has had various locations in Paris, the best known of which is at 31 rue du Dragon in Paris’s 6th arrondissement. Later, it took the name ESAG (Ecole Supérieure d’Art Graphique Penninghen), then simply Penninghen. Today, it is a private school of interior design, communication, and art direction.

[10] The Brevoort Hotel, located between 8th and 9th Streets in Manhattan, well known for a century for its restaurant (1854-1954), was demolished in 1955 and replaced by a luxurious 19-story building with 301 apartments (The New York Times, July 10, 1955).

[11] We recall the three principles that characterize Guimard’s art: logic, harmony, and sentiment.

[12] After their marriage, Hector and Adeline went on their honeymoon to Europe, specifically England and Berlin in 1909. This is attested to by postcards that Hector sent to his father-in-law in New York (New York Public Library). In addition, Hector participated in the Franco-British exhibition held in London in 1908.

[13] The words in capital letters here are also capitalized in the article in The Calumet newspaper.

[14] This refers to the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, which was postponed several times and finally took place in 1925. The United States was conspicuous by its absence.

[15] The Woolworth chain store building is located at 233 Broadway in southern Manhattan (Tribeca neighborhood). Built by architect Cass Gilbert (1859-1934), it has been designated a historic landmark and converted into apartments.

[16] The Singer factory building was erected in 1908-1909 and then demolished in 1967-68. Approximately 200 meters high, it was located at 149 Broadway.

[17] Gaston Vuitton (1883-1970) worked hard to enliven and illuminate the Champs Élysées, where his boutique was located (70 Avenue des Champs Élysées). He exhibited at the Salon de la Société des Artistes Décorateurs, of which Guimard was one of the founders.

[18] See Olivier Pons’ article “Vuitton, fan de Guimard” (Vuitton, fan of Guimard), Le Cercle Guimard, December 5, 2014.

Translation : Alan Bryden