Hector Guimard and Muller & Cie at the Castel Béranger: the end of a collaboration.

8 November 2024

As soon as they were completed in 1898, the facades of Castel Béranger caught the attention of passersby on Rue La Fontaine[1]. It must be said that their richness, both in terms of polychromy and ornamentation, was a stark contrast to the facades of the neighboring apartment buildings. At Castel Béranger, aquatic, botanical, medieval, and fantastical motifs[2] intertwine to enliven the cast iron, ceramics, and ironwork adorning the facades. This picturesque style, promoted by the public authorities at the time, even earned Castel Béranger one of the prizes in the 1898 facade competition organized by the City of Paris [3].

However, this rich decoration, which brought international fame to Castel Béranger and Hector Guimard, was not what the architect had originally planned. The elevations of the facades in the building permit submitted by Guimard in March 1895, which can currently be seen on display at the Paris Archives[4], prove this. The existence of these documents is not a discovery, as they have been known for a long time and are available for consultation. However, their high-definition scanning, carried out as part of the organization of this exhibition for the Guimard year, revealed an aborted ceramic decoration project. This was to be carried out mainly in collaboration with Muller & Cie, a company with which Hector Guimard had been working until then. Recent work by Frédéric Descouturelle and Olivier Pons, published in the book La Céramique et la Lave émaillée d’Hector Guimard[5], identifies most of the models that were to be used.

The initial Castel Béranger project

The Castel Béranger was commissioned by Élisabeth Fournier, a bourgeois woman from the Auteuil neighborhood. A widow wishing to invest her capital in real estate, at the end of 1894 she turned to the architect Hector Guimard, who also lived in the neighborhood, to build an apartment building on Rue La Fontaine.

With no constraints imposed by the client, the young architect designed a project based on the principles of Viollet-le-Duc’s rationalist school. The facade features picturesque architecture with medieval references, combined with a polychromatic effect achieved using different materials, painted cast iron and ironwork, and glazed ceramic decorations.

Before his trip to Brussels in the summer of 1895, Hector Guimard submitted the building permit for the Castel Béranger to the Paris Municipality during the second half of March[6]. This included plans for the different levels (basement plan, ground floor plan, standard floor plans, fifth and sixth floor plans) as well as elevations of the street and courtyard facades. It reveals a U-shaped building consisting of two structures organized around a courtyard, connected by a staircase. The building is aligned with the street, while the courtyard is open on the side of the Béranger hamlet.

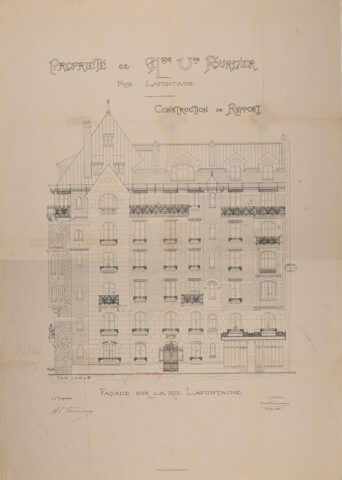

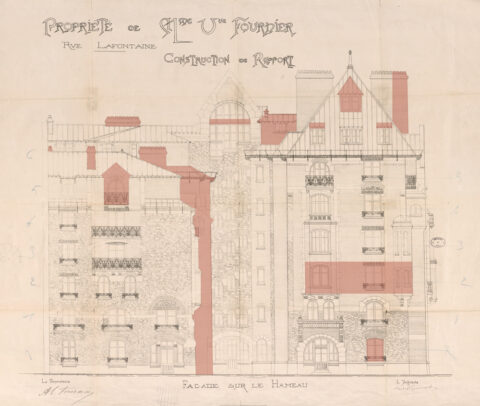

Elevation of the facade on Rue La Fontaine of the Castel Béranger, building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

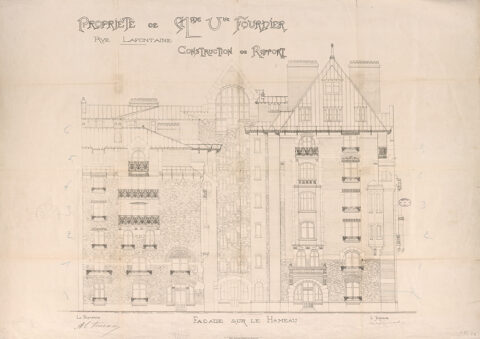

Elevation of the facade on the Béranger hamlet of Castel Béranger, building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

These drawings from the building permit are detailed enough to give a fairly accurate idea of the design that was planned at the time. The ironwork on the railings and the entrance gate reflect an undefined style that is fairly conventional and less daring than that of the Hôtel Jassedé, built two years earlier at 41 Rue Chardon-Lagache. However, floral stylizations can be seen.

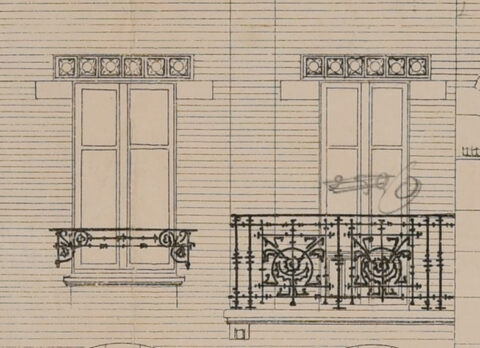

Elevation of the facade on Rue La Fontaine of the Castel Béranger (detail), building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

The flower and leaves of the sunflower, the main motif of the Hôtel Jassedé decor, can indeed be recognized once again. It is possible that, from an economic standpoint, Guimard had planned to have the central motifs, which are repeated multiple times on the facades, made of cast iron. In any case, this is what he did in the final version of the balcony railings.

Central motif of the railings on the facades of Castel Béranger, elevation of the facade on Rue La Fontaine (detail), building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

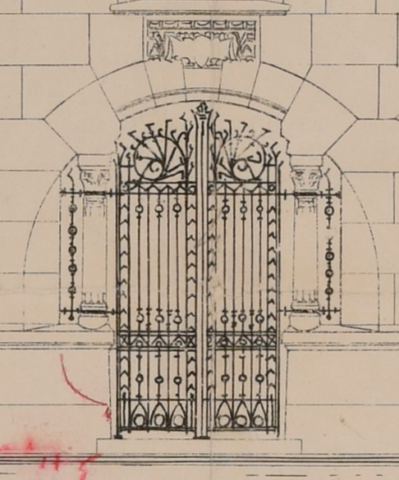

The ironwork on the gate is also not very inventive, with its evenly spaced vertical bars. Only at the top do two spiral motifs radiating outwards give it a more dynamic appearance.

Gateway to Castel Béranger, elevation of the facade on Rue La Fontaine (detail), building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

Above the storefronts of the two small shops in the last bays on the right, Guimard planned for a large sign to be inserted in front of a metal lintel. He designed a decoration interrupted by two smaller sign spaces placed in front of the spandrels of the first-floor windows.

Shop on the ground floor of Castel Béranger, elevation of the facade on Rue La Fontaine (detail), building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

This decoration is also naturalistic, with repeating floral motifs in two sizes. Probably intended to be in glazed ceramic, they appear to be framed by ironwork ending in semicircles, serrated like certain leaves, and separated from each other by floral spikes.

Decor of the shop sign on the ground floor of Castel Béranger, elevation of the façade on Rue La Fontaine (detail), building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

Castel Béranger and Muller & Cie

As shown in the building permit plans, numerous ceramic elements were planned for the facades. Thanks to the book devoted to Guimard’s ceramics and glazed lava[7], several elements of the original decoration have been identified in the Muller & Cie catalogs: metopes adorning the lintels, metopes decorating the spandrels, finials and friezes decorating the vestibule. These elements, produced and marketed by Muller & Cie, were designed and used by Guimard to decorate some of his projects prior to Castel Béranger.

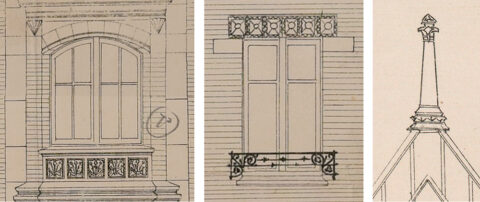

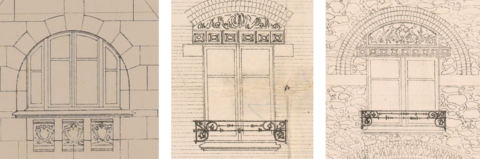

Metopes and finials designed by Guimard and produced by Muller & Cie, shown in the facade elevations of the building permit for the Castel Béranger, building permit for the Castel Béranger, facade on Rue La Fontaine (windows) and facade on Hameau Béranger (finials), March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

In the initial project, Guimard had planned to reuse the lintel design created in 1893 for the Hôtel Louis Jassedé on Rue Chardon-Lagache[8]. As two years earlier, the metope model listed as number 13 in the second Muller & Cie catalog was to adorn the metal lintels of the windows of the Castel Béranger. The design of the facades shows that the metopes were to be enclosed in screwed iron frames, similar to the corbelled lintel of the Villa Charles Jassedé, also built in 1893.

Metope no. 13 designed by Hector Guimard and published by Muller & Cie; left: Muller & Cie, metope no. 13, Muller & Cie catalog no. 2, 1904, coll. Le Cercle Guimard; right: lintel of the Hôtel Jassedé, 1893, 41 rue Chardon-Lagache. Photo N. Christodoulidis.

The model used to decorate the spandrel of certain windows is metope no. 35 by Muller & Co. It was also used at the Hôtel Jassedé to embellish the base of the building. Although its appearance contrasts sharply with model no. 13, it was indeed designed by Guimard, as evidenced by the price list in the 1904 Muller et Cie catalog, which associates each model with the name of the architect who designed it.

Metope no. 35 designed by Hector Guimard and published by Muller & Cie; left: Muller & Cie, metope no. 35, Muller & Cie catalog no. 2, 1904, coll. Le Cercle Guimard; right: base of the Hôtel Jassedé, 1893, 41 rue Chardon-Lagache. Photo F. Descouturelle.

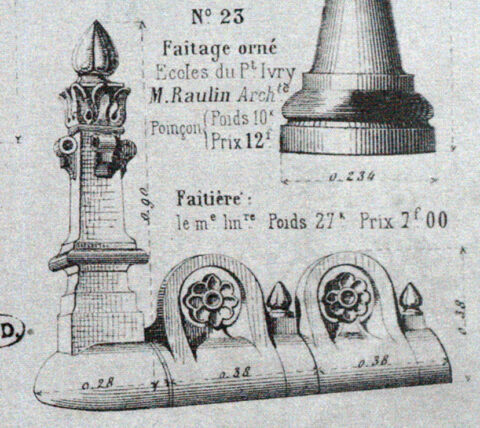

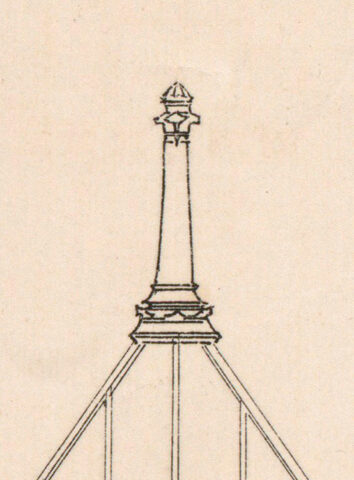

As is the case today, the pavilion roof at the left end of the building bordering La Fontaine Street was to be crowned with a ridge finial. Unlike the current finial, which appears to be made of cast iron, the original was to be made of ceramic and manufactured by Muller & Co.

The lack of detail in its representation in the building permit elevations makes it impossible to identify with certainty the model that was to be used. However, we can still hypothesize that it was a new transformation of finial no. 23 designed by Gustave Raulin[9] for the schools in Ivry-sur-Seine (1880-1882).

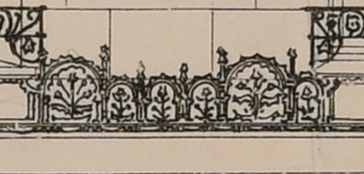

Roof finial no. 23 designed by Gustave Raulin for the schools of Ivry, Muller & Cie catalog no. 1, pl. 12, 1895–1896, coll. Bibliothèque des Arts décoratifs.

After using this model at the café-concert restaurant Au Grand Neptune in 1888, Guimard also used it to crown the roof of the Charles Jassedé villa in Issy-les-Moulineaux[10].

Roof of Charles Jassedé’s villa with finial no. 23 in Issy-les-Moulineaux, 1893. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

Shortly before, for the Hôtel Jassedé, he had transformed this finial by removing the side scrolls and adding scrolls taken from finial no. 22 in the Muller & Cie catalog.

Current state of a ridge finial on the Hôtel Jassedé, 41 rue Chardon-Lagache, Paris, 1893. Photo by N. Christodoulidis.

Although seemingly quite different from this latter variant, the design of the first version of the finial for Castel Béranger bears many similarities to the original finial no. 23. Like Raulin’s model, Guimard’s design features an end that resembles a flower bud. Both prototypes feature a spread of leaves at their base. The main difference lies in the round[11], elongated section and the absence of scrolls on the shaft.

Finial of the Castel Béranger, building permit, elevation of the courtyard façade, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives.

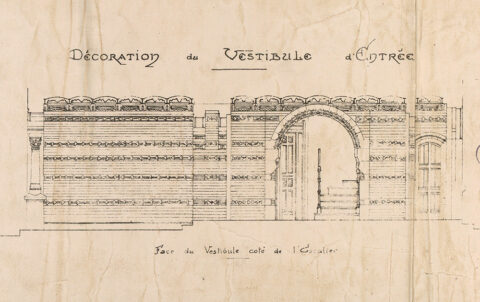

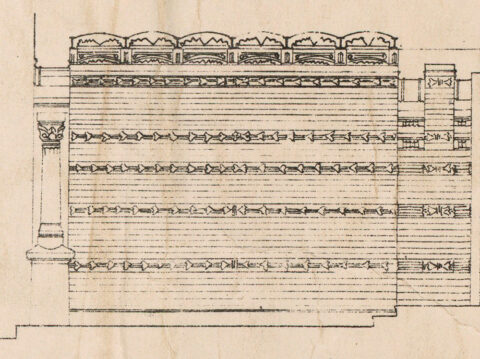

The walls of the vestibule, meanwhile, were initially intended to feature a design very different from the current one, consisting of bubbling sandstone panels created by Bigot. In a more traditional style, the walls were to be decorated with five horizontal floral friezes. Their appearance is similar to that of the vertical cloisonné panels used by the architect in 1891 to border the windows of the veranda of the Hôtel Roszé[12]. This is the model published under No. 127 in the second Muller & Cie catalog. Guimard seems to have planned to separate these friezes with beds of glazed bricks, in the style of the vestibule at 66 rue de Toqueville in Paris, created by Muller & Cie in 1897 under the direction of architect Charles Plumet[13].

Cross-section of the vestibule and hall of Castel Béranger, building permit, undated, detail, Paris Archives

Cross-section of the entrance hall of Castel Béranger, building permit, undated, detail, Paris Archives

Panel no. 127 designed by Hector Guimard and published by Muller & Cie, Muller & Cie catalog no. 2, 1904, coll. Le Cercle Guimard.

Detail of panel no. 125, cloisonné enameled earthenware, produced by Muller & Co., Le Cercle Guimard collection. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

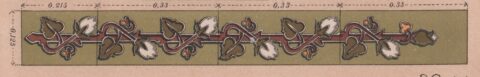

Two tympanums and a ceramic metope model, visible on the facade elevations of the Castel Béranger building permit, have not yet been identified in the Muller & Cie catalogs. It is likely that these pieces were also to be produced by the company[14]. However, it is also possible that Guimard had already planned to commission Gilardoni & Brault to produce them.

Metopes and tympanums designed by Guimard for the Castel Béranger, to be produced by an as yet unidentified company, building permit for the Castel Béranger, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives

During his stay in Brussels, Hector Guimard had the opportunity to meet architects Victor Horta and Paul Hankar, leading figures of Belgian Art Nouveau. In particular, he found in Horta’s work an integration of decoration and structure that was unparalleled elsewhere and which revolutionized his vision of modern architecture. After this trip, Guimard abandoned the figurative botanical decorations designed under the influence of Nancy[15] in favor of ornamentation that tended more toward abstraction. He borrowed the whip-like line motif from Horta, but he also drew on other, older sources[16].

Thus, upon his return to Paris, Guimard redesigned the entire interior of the Castel Béranger, following the principle of the total work of art that had so impressed him in Horta’s work. In addition to designing the elements for the decoration and layout of the apartments (wallpaper, window handles, door handles, stained glass windows, fireplaces, etc.), the architect transformed all the ornamentation on the facades and in the vestibule.

Unlike the interior design, it was impossible for the architect to modify the plans that had already been drawn up, as the structural work had begun as soon as he returned from Belgium. A careful comparison of the plans and facades drawn up for the building permit with those published in the Castel Béranger portfolio[17] reveals that the layout of the spaces and the overall volume of the buildings are almost identical. The slight notable modifications (openings, turrets, chimney stacks, volume of the courtyard side of the building) are certainly the result of the natural process of the project, leading the architect to constantly question his work. These therefore undoubtedly appeared during the drawing up of the working plans for the structural work craftsmen, probably produced before Guimard’s departure for Belgium.

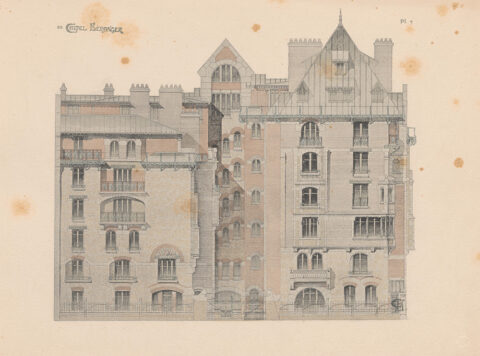

Elevation of the facade of Castel Béranger in the hamlet of Béranger, building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives. Color coding of structural modifications (in red).

Elevation of the facade of Castel Béranger in the hamlet of Béranger, portfolio of Castel Béranger, pl. 7, 1898, ETH Library Zurich.

If we compare the drawings of the facades in the building permit application with those published after construction in the Castel Béranger portfolio, we see that all of the ironwork originally planned was replaced by alternative designs. The floral character disappeared in favor of a new style, partly abstract and partly fantastical.

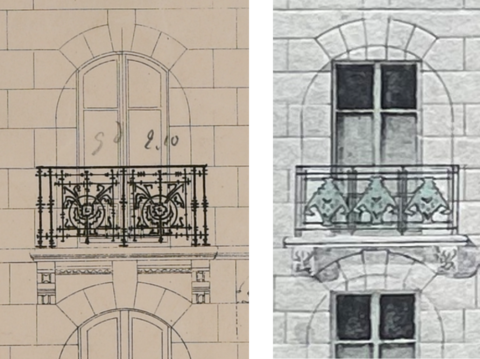

Modifications to the design of the railings; left: elevation of the facade on Rue La Fontaine, building permit, March 15, 1895, Paris Archives; right: elevation of the façade on Rue La Fontaine, Castel Béranger portfolio, pl. 2, 1898, Bibliothèque du Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

Similarly, all the ceramic decorations specified in the building permit were replaced. Guimard then ended his collaboration with Muller & Cie, even though a few months earlier he had been considering placing an order with them. This break was all the more surprising given that, until then, he had exclusively used Muller & Cie for all his projects requiring architectural ceramics: the café-concert restaurant Au Grand Neptune (1888), the Roszé hotel (1891), the Jassedé hotel (1893), the Charles Jassedé villa (1893), the Delfau hotel (1894), and the Carpeaux gallery (1894-1895). This change of suppliers benefited two competing companies. The first was Gilardoni & Brault, a tile factory which, like Muller & Cie, had diversified into architectural decoration. Metopes No. 13, produced by Muller and initially intended for window lintels…

Metope no. 13 published by Muller & Cie, window lintel of the Hôtel Jassedé, 41 rue Chardon-Lagache, Paris, 1893. Photo N. Christodoulidis.

…were thus replaced by new metopes, also encased in iron blades.

Metope probably produced by Gilardoni & Brault, window lintel from Castel Béranger. Photo by N. Christodoulidis.

As for the metopes No. 35 planned as spandrels for certain windows, they too have been replaced by new models.

Left: metope no. 35 produced by Muller & Co. and used for the base of the Jassedé hotel (41 rue Chardon Lagache, 1893), originally intended to adorn the spandrels of certain windows of the Castel Béranger; Right: metope produced by Gilardoni & Brault, ultimately used to decorate the spandrels of some of the windows of Castel Béranger. Photos by F. Descouturelle and N. Christodoulidis.

The second company Guimard turned to was Alexandre Bigot’s, which was still new but whose reputation was rapidly growing. It worked exclusively with glazed stoneware and was firmly positioned in the modern style.

Entrance hall of Castel Béranger, glazed sandstone by A. Bigot. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

Why did this collaboration with Muller & Cie come to an end?

There is no obvious explanation for this breakup. The reasons cannot be technical, since Gilardoni & Brault offered the same types of products as Muller & Cie, available in plain terracotta, glazed earthenware, and glazed stoneware. It is also doubtful that the break was solely for stylistic reasons. While Guimard’s sudden change in style may have come as a surprise to Muller & Cie, we know from its catalogs that the company welcomed new stylistic trends and produced a considerable number of modern designs.

On the contrary, until then, Gilardoni & Brault’s products had remained rather cautiously eclectic. Could this tile factory, suddenly enamored with modernity, have “poached” Guimard? In any case, the large order for his stand at the 1897 Ceramics Exhibition[18] confirms his interest in the architect’s new style, as he did not hesitate to bear the cost of manufacturing numerous molds. For several years, the company even supported Guimard’s research into shaped pieces, particularly vases.

Other, undoubtedly more petty reasons can be put forward to explain the emergence of a disagreement between the architect and Muller & Cie. First of all, Guimard may have been annoyed by the liberties taken by the tile factory with regard to his designs. The company did not hesitate to modify some of the architect’s designs and to create new models in a similar style, undoubtedly without paying him for them[19].

From Muller & Cie’s point of view, Guimard’s previous models had probably not been as successful as expected. When Guimard, instead of continuing to amortize them at Castel Béranger, proposed to create and publish new ones, the company may have backed away from an investment it considered too risky, choosing to end its seven-year collaboration with Guimard.

Maréva Briaud, Doctoral School of History, University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne (ED113), IHMC (CNRS, ENS, Paris 1).

Notes

[1] “Curious onlookers and astonished passers-by stopped to examine this original façade at length, so different from the surrounding houses.” L. Morel, “L’Art nouveau,” Les Veillées des chaumières, May 17, 1899, p. 453.

[2] This aspect will be discussed in a presentation at the Guimard study day organized by the Paris City Hall on December 3, 2024, and in the article that will follow.

[3] The results of the competition were not announced until 1899, and Guimard immediately had them engraved on the façade of the Castel Béranger.

[4] Guimard, architectures parisiennes, exhibition at the Archives de Paris, organized in partnership with Le Cercle Guimard, from September 20 to December 21, 2024. See also the exhibition journal available on site: Le Cercle Guimard. Exposition aux archives de Paris, no. 4, September 19, 2024.

[5] F. Descouturelle, O. Pons, “Guimard et Muller & Cie,” La Céramique et la lave émaillée d’Hector Guimard, Paris, Le Cercle Guimard, 2022.

[6] The building permit plans are dated March 10, 1895, and the facades are dated March 15, 1895.

[7] F. Descouturelle, O. Pons, op. cit.

[8] Ibid., p. 34.

[9] Hector Guimard was attached to Gustave Raulin’s studio during his studies at the École des Beaux-Arts.

[10] F. Descouturelle, O. Pons, op. cit., p. 42.

[11] The current finials on the roof of the Jassedé hotel garage are round in section. They are finial no. 4 in the 1903 Muller & Cie catalog, pl. 16, and may be the version of the model redesigned by Guimard ten years earlier.

[12] F. Descouturelle, O. Pons, op. cit., p. 31.

[13] Ibid, p. 21.

[14] Muller et Cie was able to produce any model on request.

[15] Guimard’s representations of flora are figurative but do not achieve the precision of Émile Gallé’s naturalistic drawings. They even slightly anticipate the stylizations of Eugène Grasset.

[16] See the article “Guimard and the auricular style” published on our website.

[17] H. Guimard, L’Art dans l’habitation moderne/Le Castel Béranger, Paris, Librairie Rouam, 1898. These watercolor plans are generally accurate but occasionally deviate from reality.

[18] National Exhibition of Ceramics and All Arts of Fire in 1897 in Paris, at the Palais des Beaux-Arts.

[19] F. Descouturelle, O. Pons, op. cit., p. 48.

Translation : Alan Bryden