Guimard, brick by brick

Throughout his career as an architect, Guimard paid close attention to the variety of bricks available on the market. In this article, we provide an overview of their use, which may be expanded based on more comprehensive studies of the building materials he used in his buildings.

Very roughly speaking, it should be noted that North of the Loire, in regions rich in limestone, fired clay bricks were rarely used until the Renaissance, when, in imitation of Italian buildings, they became a sought-after material, despite their production cost, and were even used in the construction of castles in the 16th and 17th centuries. Its production cost fell between the 18th and 19th centuries because of its gradual industrialization. From then on, its increasing use in economical construction led to a decline in its value as a material and its relegation to the status of a poor material. It was against this trend that, from the second half of the 19th century onwards, brick gradually regained its prestige thanks to more sophisticated production. A variety of tones was obtained by composing pastes with varying amounts of iron oxide, or by coloring or glazing its faces. This expansion of the product range naturally accompanied the movement in favor of polychrome urban facades initiated by Jacques-Ignace Hittorff (1792-1867) and later by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879).

Terracotta brick

Influenced by Viollet-le-Duc and concerned with both originality and economy, Guimard made extensive use of brick in his early villas, built before Castel Béranger in the 16th arrondissement and in the western suburbs of Paris. He mainly used pink-orange and red bricks, sometimes punctuated with glazed bricks.

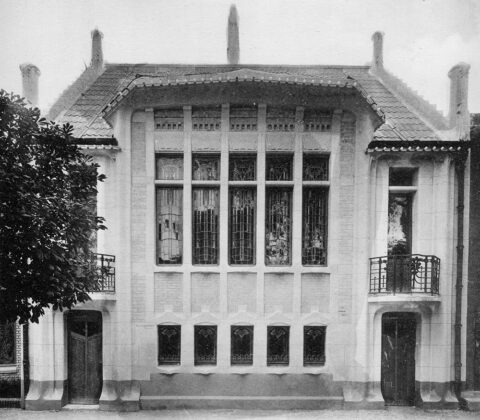

Hôtel Roszé, 1891, 34 rue Boileau, Paris XVIe, Photo F. D.

Hôtel Jassedé, 1891, 41 rue Chardon-Lagache, Paris XVIe, Photo F. D.

They alternate with millstone and cut stone, which is rarer and chosen for certain key elements of the facades: capitals, lintels, cornices, etc. The result is a mixture of colors which, combined with the particularly colorful ceramics, reinforces the picturesque appearance of these residences.

The more aristocratic-looking Hôtel Delfau stands out with its almost monochrome façade, which mainly uses straw-yellow brick that blends in with the cut stone used for the front section and its large dormer window. Guimard deliberately limited the use of red brick to simple courses that highlight the cornices, just as he restricted the color of the architectural ceramics to blue alone.

Hôtel Delfau, 1894, 1 ter rue Molitor, Paris XVIe, Photo F. D.

The advent of Art Nouveau in 1895 did little to change this choice of materials. An economical building such as the École du Sacré-Cœur simply used less stonework that was less sculpted than on the Castel Béranger. For the Castel Henriette, rubble stone in opus incertum replaced millstone.

École du Sacré-Cœur, 1895, 9 avenue de la Frillière, Paris XVIe, Photo F. D.

Upper floors of the street facade of the Castel Béranger, 1895–1898, 14 rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine, Paris XVIe. Photo F. D.

Detail of the courtyard façade of the Castel Béranger, 1895–1898, 14 rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine, Paris XVIe. Photo F.

Generally, bricks have the brickworks’ mark embossed on one of their long, narrow sides. So far, we have only found the “CB” logo on the bricks of the Hôtel Roszé and that of the Chambly brickworks (in the Oise region) on those of the Castel Val. It is possible that in most cases, Guimard instructed the contractor to hide the marks by exposing the opposite long side.

Detail of the street facade of the Hôtel Roszé, 1891, 34 rue Boileau, Paris XVIe. Photo F. D.

Detail pf the façade of Castel Val, Auvers-sur-Oise (Val d’Oise), 1902-1903. Photo F. D.

For the Humbert de Romans concert hall (1898-1901), thanks to the attachment plan preserved in the Guimard collection at the Musée d’Orsay, we know precisely the types of bricks used for the masonry. A top-quality Sannois brick (white) was used for the main facade and the patronage. It was doubled with a Belleville brick, also top quality.

For the Castel Béranger, on smaller areas of the street facade and in the courtyard, Guimard also used glazed terracotta bricks, with a color that gradually changed from light blue to beige.

Detail of the courtyard façade of the Castel Béranger, 1895–1898, 14 rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine, Paris XVIe, Photo F.

It is likely that they came from the Gilardoni & Brault tile factory, as this company is mentioned in the list of suppliers for Castel Béranger. The company also supplied the artistic glazed ceramics used on the façade and some of the chimney narrowings in the apartments.

Hector Guimard, L’Art dans l’Habitation moderne/Le Castel Béranger (portfolio of Castel Béranger), list of suppliers (detail), Librairie Rouam, 1898. Private collection.

It is noteworthy that in all cases where bricks of different colors were used, Guimard never created alternating color patterns as seen on many buildings of that period, because these designs, which would necessarily be geometric, would have competed with his own decorations. To create curved patterns, large flat surfaces would have been required, and the result would not necessarily have been satisfactory. At most, he contented himself with beds of different colors to highlight cornices or simulate a bed frame.

Detail of the façade on Rue Lancret of the Jassedé building (1903–1905), Paris XVIth arrondissement. Photo F. D.

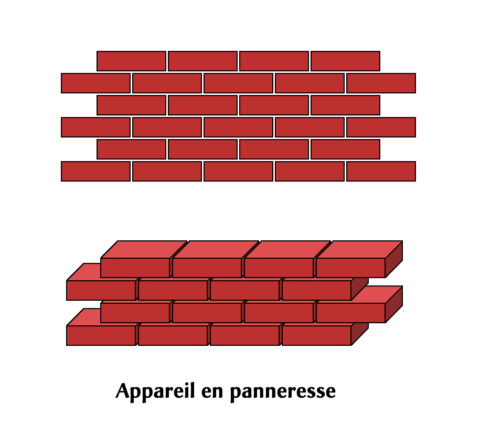

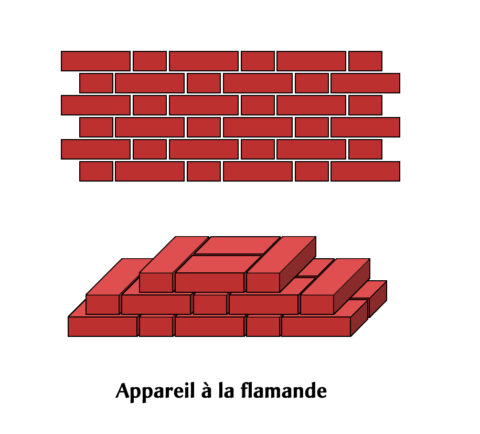

Few types of masonry are used. These are mainly stretcher bond and Flemish bond[1], which alternate headers (the smaller side) and stretchers on each course.

.

.

Panneresse and Flemish devices. Drawings by F. D.

The small size of the brick makes it easy to curve a wall. However, Guimard did not immediately exploit this possibility and stuck to flat walls in his early buildings. Even when he curved the central span of the Villa Berthe in Le Vésinet (1895) or the oriel window of La Bluette in Hermanville (1899), he used cut stone, which was more expensive to work with. He probably preferred the softer surface of the stone, which better complemented the movement he was creating.

Main façade of the Villa Berthe, Le Vésinet (Yvelines), 1896. Photo Nicolas Horiot

It was not until the Castel Henriette (1899) that curved brick sections appeared. For the first time, its design gave prominence to curved elevations, but these were mainly constructed using opus incertum rubble stone. A few years later, Castel Val in Auvers-sur-Oise (1902-1903) was the finest example of curved facades using brick, a technique that Guimard repeated shortly afterwards in a more discreet manner on the Jassedé building, at the corner of Avenue de Versailles and Rue Lancret (1903-1905) .

Facade of the first floor of Castel Val, Auvers-sur-Oise (Val d’Oise), 1902-1903. Photo Nicolas Horiot.

Street facade of the Jassedé building at the corner of Avenue de Versailles and Rue Lancret, Paris XVIth arrondissement, 1903-1905. Photo F. D.

Sand-lime brick

Around 1904, Guimard began using sand-lime brick. This material is not obtained by firing natural or reconstituted clay: it is an artificial stone similar to cement.

Sand-lime bricks laid in Flemish bond on the street façade of the Hôtel Mezzara, 60 rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine, Paris XVIth arrondissement, Photo F. D.

Even if the principle behind it is much older, it was not manufactured industrially until the late 19th century[2]. Composed of 90% silica sand, quicklime (calcined limestone), and water, the mixture is molded into bricks that are compressed and then hardened in a steam boiler. On close inspection, you can see the coarse sand and gravel that make up the mixture. As a result, while terracotta bricks are virtually unalterable, after a century these bricks show signs of wear, with the grains gradually coming loose.

Sand-lime bricks on a chimney stack at the Hôtel Mezzara, 60 rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine, Paris XVIe. Photo Nicolas Horiot.

On the other hand, its high density makes it heavy, and its thermal inertia is poor. However, this material also has many qualities, including low cost due to low energy consumption during production, compressive strength that allows it to be used in load-bearing walls, fire resistance, and good acoustic quality.

Guimard’s use of this material coincided with a stylistic shift away from the somewhat garish polychromy of his early work toward a more discreet elegance. The gray-beige color of sand-lime brick blends in well with that of cut stone.

As he had done earlier with terracotta brick, Guimard first experimented with this new material alongside rubble stone for villas and suburban houses such as the Castel d’Orgeval in Villemoisson-sur-Orge (1904), where it highlights the windows and individualizes remarkable surfaces. In contrast, it appears very discreetly on the villa in Eaubonne (c. 1907), then a little later on the Châlet Blanc in Sceau (1909), and finally in a more prominent way on the Villa Hemsy in Saint-Cloud (1913).

Window on the ground floor of the street-facing façade of the villa at 16 rue Jean Doyen in Eaubonne (Val d’Oise), c. 1907. Photo F. D.

But it is in his urban constructions, starting with the Hôtel Deron-Levent (1905-1907), that sand-lime brick seems to be most appropriate. Next came the Trémois building on Rue François Millet (1909-1911), the “modern” buildings on Rue Gros, La Fontaine and Agar streets, his mansion on Avenue Mozart (1909-1912) and the Hôtel Mezzara on Rue La Fontaine (1909-1911), where sand-lime brick is used in conjunction with cut stone, the surface of which varies according to the desired luxury effect.

Street facade of the Mezzara Hotel, 60 rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine, Paris XVIth arrondissement, rubble stone base, sand-lime brick facing, window sills and frames in cut stone. Photo F. D.

Guimard also used different brickwork patterns with sand-lime brick. The Hôtel Guimard at 122 Avenue Mozart (1909), with its particularly dynamic façade, is a good example of how these techniques were used to reduce the thickness of the walls and lighten the masonry towards the top, adapt to the folds in the façades, and reinforce certain walls at specific points.

Detail of the second and third floors of the façade of the Hôtel Guimard. Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs, donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

The main body of its walls is constructed using Flemish bond, resulting in walls 45 cm or 22 cm thick. To create the curves and begin the folding of the facade, header bond was used, sometimes supplemented by alternating multiple header bond to reinforce the strength of the walls, particularly around certain openings. In the upper parts, the use of a regular header bond technique made it possible to lighten the masonry of the top floor at the loggia level, resulting in walls only 11 cm thick.

Detail of the second and third floors of the facade of the Hôtel Guimard. Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs, donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

It was also from 1909 onwards (Hôtel Guimard, courtyard of the Trémois building, Hôtel Mezzara) that a model of bricks with rounded corners began to appear, particularly at the jambs of the windows, where they softened the transition from one plane to another.

Detail of the left bay on the first floor of the street façade of the Hôtel Mezzara, 60 rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine, Paris XVIe. Photo F. D.

After the war, sand-lime brick was still used on the Franck building on Rue de Bretagne (1914-1919). A little later, it gave way to yellow terracotta brick for the luxurious building on Rue Henri-Heine (1926), where Guimard used it only on the top floors, where it is less visible.

Yellow terracotta brick and sand-lime brick on the fifth floor of the street facade of the Guimard building at 18 rue Henri-Heine, Paris XVIe, 1926. Photo F. D.

But it made a strong comeback with affordable buildings such as the Houyvet building, Villa Flore (1926-1927), and the buildings on Rue Greuze (1927-1928), and undoubtedly with his villa La Guimardière in Vaucresson (1930).

Rear facades and overlooking Villa Flore of the Houyvet building, Paris XVIth arrondissement, 1926-1927. Photo F. D.

Parapet and window on the fifth floor of the façade overlooking Villa Flore on the Houyvet building, Paris 16th arrondissement, 1926–1927. Photo F. D.

Detail of the street facade of the first floor of 38 Rue Greuze, Paris XVIe, 1927-1928. Photo F. D.

As can be seen in the previous photos, after World War I Guimard introduced effects of volume and therefore light by placing certain bricks in a different way in relation to the surface, for example protruding, recessed, or slanted. These techniques have been well known for centuries and are used to emphasize vertical or horizontal lines, or to punctuate a flat surface. However, just as he refused to use repetitive patterns of alternating brick colors, he also did not take advantage of the possibility of playing with the relief of brick walls during the first part of his career, rightly considering that their surface should remain neutral and not compete with his own decorative motifs (carved in stone or modeled in ceramic), which he reserved for limited locations. However, caught up in the general stylistic evolution that initially advocated the geometrization of decoration before its gradual abandonment, Guimard decided to introduce these surface effects as he abandoned his personal decorative motifs. He was certainly not the only one to use this motif of bricks placed at a 45° angle, with the angle flush with the surface (below).

Detail of the street facade of the second floor of the Guimard building at 18 rue Henri-Heine, Paris XVIe, 1926. Photo F. D.

But perhaps he is the inventor of this original pattern, in which one brick is rotated 30° and the next is symmetrical to it. On the course above, the same sequence is offset by one course width.

Lintel of a window on the fifth floor of 36 Rue Greuze, Paris XVIe, 1927–1928. Photo F. D.

Asbestos brick

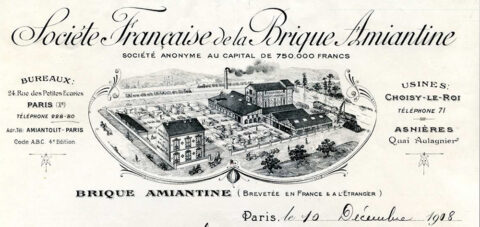

Also known as asbestolite, asbestos brick was manufactured in France in Choisy-le-Roy from 1904 onwards by the Société française de la brique amiantine using asbestos fiber imported from Canada.

Letterhead of the Société Françaises de la Brique Amiantine, letter dated December 10, 1908, photograph taken from Pierre Coftier’s article, “La brique amiantine de Choisy-le-Roy” (Asbestos brick from Choisy-le-Roy), L’actualité du Patrimoine, no. 8, Dec. 2010. All rights reserved.

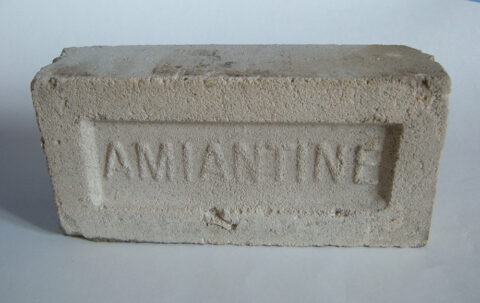

The addition of this mineral[3] was intended to increase the (already good) fire resistance of sand-lime bricks, improve their low insulating properties, and even provide an antifungal effect. The product, which could be colored, was seen as innovative compared to simple sand-lime bricks and was therefore highly valued. To clearly differentiate them, the “Amiantine” brand name was embossed in a recess on one of the two large faces of the bricks.

Large side of an asbestos brick. Photograph taken from Pierre Coftier’s article, “La brique amiantine de Choisy-le-Roy” (The asbestos brick of Choisy-le-Roy), L’actualité du Patrimoine, no. 8, Dec. 2010. All rights reserved.

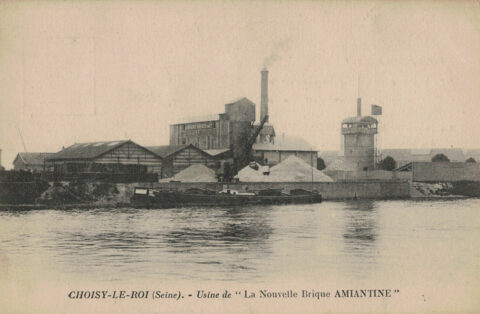

The Choisy-le-Roy site was acquired in 1922 by Lambert frères & Cie.

Lambert Frère & Cie factory in Choisy-le-Roy, old postcard. Private collection.

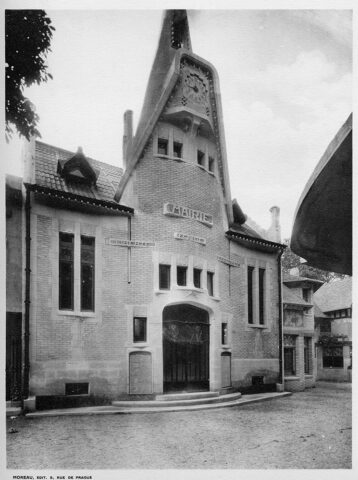

Guimard appears to have used these products for the first time in 1925 at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts for his participation in the French Village[4] as part of the Modern Architects group, of which he was vice-president.

As the designer of the village town hall, he used asbestos brick[5] more extensively on the main façade than on the rear façade. This brick is mentioned, along with the Lambert cement factory, in groups of three stretching courses, clearly visible in four locations: two on the main façade and two on the rear façade. The Maison du Tisserand[6] by architect Émile Brunet, adjoining the town hall on the right, and undoubtedly other buildings in the village also used this material. The tiles on the town hall were made of weathered fiber cement and were also supplied by the Lambert cement factory[7]. This touches on one aspect of the French Village which, like other similar events, was only able to balance its budget by supplying materials at preferential rates in exchange for discreet but effective advertising.

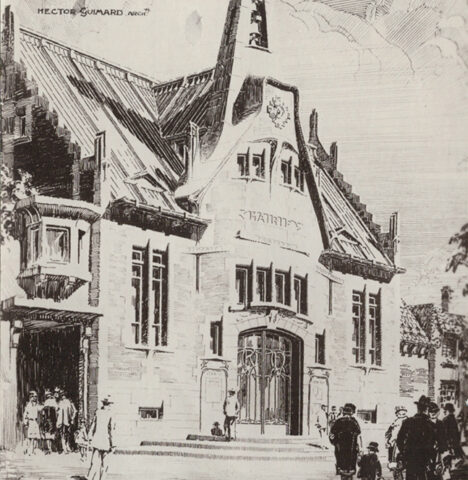

Main façade of the French Village town hall at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim, Charles Moreau, 1926, pl. 2. Private collection

Rear facade of the French Village town hall at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts (detail), 1925, portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim, Charles Moreau, 1926, pl. 3. Private collection.

As proof of Guimard’s constant interest in new building materials and their evolution, he exhibited in the large hall on the ground floor of the town hall “some of the materials used in its construction[8].” These included, for example, two types of brick whose exact use in the town hall is unknown: “the double 6 x 2222 brick, hollow, easy to use,”[9] whose manufacturer is unknown, and bricks produced by the “Société de Traitement des Résidus Urbains” (Urban Waste Treatment Company) run by a certain Grangé. In an article devoted to new products at the 1925 Exhibition, the magazine L’Architecture shed some light on their manufacturing process:

“[…] The bricks and cinder blocks of the Société de Traitement Industriel des Résidus Urbains, manufactured using silico-calcareous processes with clinkers (slag) from the incineration of household waste in the city of Paris, obtained by melting and vitrification at high temperature (1,200°C) of the non-combustible products contained in household waste. [10] “

To encourage players in the construction industry to discover its products, Grangé used an advertising card with a drawing of the French Village town hall by Alonzo C. Webb (1888-1975)[11] on the back, which also appeared in La Construction Moderne.

A.C. Webb, drawing of the main façade of the French Village Town Hall, card issued by the Urban Waste Treatment Company inviting people to visit the French Village Town Hall exhibition hall, front. Private collection.

Card issued by the Urban Waste Treatment Company inviting visitors to visit the exhibition hall at the French Village town hall, reverse side. Private collection.

Another supplier of materials to Guimard, a quarry operator in Thorigny-sur-Marne and manufacturer of special plasters, was also known to us. The magazine L’Architecture also mentioned his products on display in the main hall of the town hall:

“[…] Notably Taté products, ready-made for coatings and renovations imitating stone, classified into three categories and whose names, bearing only a tenuous relationship to the designations indicated in parentheses, are as follows: lithogène (slow setting), pétra stuc (fast setting), alabastrine (alabaster alum plaster).”

We are certain that “petra-stuc” was used in the construction of the town hall, as we can make out the name written on the base above the basement window[12]. We can also read the name Taté on the photograph.

Main façade of the French Village town hall at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts (detail), 1925, portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim, Charles Moreau, 1926, pl. 2. Private collection.

This fairly dark-colored “petra-stucco” used for the base is more visible in the photograph of the rear facade of the town hall.

Rear facade of the French Village town hall at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, 1925, portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim, Charles Moreau, 1926, pl. 3. Private collection.

The use of this product would be anecdotal if Taté had not harbored a deep resentment toward Guimard, undoubtedly over a financial matter. But instead of settling this dispute through the courts, either civil or commercial, upon learning that the General Commission for the Decorative Arts Exhibition had proposed Guimard for the Cross of Knight of the Legion of Honor, Taté sent a letter of denunciation[13] to the Order’s chancellery, which had the effect of delaying his appointment for four years.

After the 1925 exhibition, Guimard once again used products containing asbestos. Like his colleague Henri Sauvage, he used fiber cement tubes produced by the Éternit company. These can be found in particular on the two buildings on Rue Greuze, where they serve an essentially decorative function, their volume emphasizing the verticality of the bow windows and bays. The plans show that they are half-cylinders.

Building 38 rue Greuze, Paris XVIe. Photo F. D.

These fiber-cement tubes appear to have a more structural function on the terraces of the 6th and 7th floors, similar to their use two years later by Sauvage, who experimented with using them for load-bearing walls in individual homes built with prefabricated elements.

Terrace on the 7th floor of the building at 38 Rue Greuze, Paris, 16th arrondissement. Photo: F. D.

Finally, they are also present at La Guimardière, the villa that Guimard built for himself in 1930 in Vaucresson, using disparate materials that undoubtedly came from his past projects. Unsurprisingly, brick is still very much present in this final construction.

Villa La Guimardière in Vaucresson (Yvelines), Decorative Arts Library, donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Frédéric Descouturelle

Thanks to Nicolas Horiot for the details provided about the Humbert de Romans hall and the Guimard hotel.

Notes

[1] There are variations in the literature regarding the names of the different types of equipment, which can lead to confusion, particularly between English and Flemish equipment.

[2] Granger, Albert, Pierre et Matériaux artificiels de construction, Octave Douin éditeur, Paris, n.d.

[3] The first deaths due to pulmonary fibrosis caused by asbestos were recorded around 1900, but it was not until 30 years later that cases of mesothelioma (cancer of the pleura) were attributed to it. The link was not formally established until the 1950s, but the harmful effects of asbestos were then denied for a long time by the entire production industry and by many politicians, resulting in pollution that is now extremely costly to eradicate.

[4] The French Village was one of the most popular sites in the exhibition, although it was not the best understood by critics and subsequently the most studied by art historians. Rationalist and modern without being revolutionary, rural without being regionalist, it presented, gathered together in a fictional village, different houses, shops, and services, treated in a modern style favoring new materials but without neglecting traditional materials. See Lefranc-Cervo, Léna, Le Village français: une proposition rationaliste du Groupe des Architectes Modernes pour l’Exposition Internationale des arts décoratifs de 1925, Research thesis (2nd year of 2nd cycle) supervised by Ms. Alice Thomine Berrada, École du Louvre, September 2016.

[5] Goissaud, Antony, “La Mairie du Village,” La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925.

[6] Goissaud, Antony, “La Maison du Tisserand,” La Construction Moderne, October 11, 1925.

[7] “Among the exhibitors [inside the main hall], the Lambert Frères company naturally stands out, having supplied the asbestos bricks and tiles for the houses in the Village […]”. Goissaud, Antony, “La Mairie du Village,” La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925.

[8] “New products at the 1925 Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts,” L’Architecture no. 23, December 10, 1925.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid. These combustion residues are commonly referred to as clinker.

[11] See the note on this subject in the article on Guimard’s participation in the 1925 Exhibition.

[12] The editor of La Construction Moderne confused it with a “strongly tinted gray stone,” Goissaud, Antony, “La Mairie du Village” La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925.

[13] We reserve the reproduction of this letter for a future article recounting the twists and turns of this affair.

Translation: Alan Bryden