Eriksson espagnolettes, handles, and lock

In September 2013, a pair of espagnolette boxes and handles (without top or bottom strikes or rod guides) was sold on eBay under the title “Pair of Art Nouveau handles in silver-plated bronze attributed to Hector Guimard (Van de Velde) .” As the reference to Henry Van de Velde was simply included to attract the attention of a more international audience, the question of attribution to Hector Guimard immediately arose. No examples of these espagnolette locks were known to exist in any of his buildings, but the discovery of a new model is always possible.

Pair of espagnolette locks. eBay sale on September 22, 2013. Photo provided by the seller.

Most Guimard connoisseurs had noted a certain similarity between these objects and his style but had been put off by the somewhat overly naturalistic appearance of the casing, whose ends evoke leaves or flames. Nevertheless, attribution to Guimard was not impossible, as on rare occasions he did incorporate details taken directly from nature into his compositions. And in the case of these espagnolette locks, it was interesting to note the emphasis on the handcrafted appearance of the material, reminiscent of the porcelain doorknobs created for the Castel Béranger and widely used by Guimard thereafter. Indeed, on closer inspection, the espagnolette handle appears to have been roughly kneaded, as if strips of clay had been pressed and twisted by the modeler’s hand.

Pair of espagnolette locks. eBay sale on September 22, 2013. Photo provided by the seller.^

The ends of the casing show the same type of workmanship: thVee material appears to have been stretched and turned.

As for the case, its central mass, smooth and rounded like a core, appears to have been discovered under a thick layer of clay that had been rolled back at its four corners.

But this visual aspect alone would not have been sufficient to attribute them to Guimard, had it not been for the image of a lot sold by Sotheby’s New York in 2005. This lot included two door handles and four espagnolette handles identical to those in the eBay listing, two reddish in color (probably copper) and two bronze or brass in color. It was immediately clear that the door handles were the “long” version of the espagnolette handles.

These six objects were then attributed to Guimard by the auction expert, which did not offer much guarantee. But a few years later, this attribution was confirmed when a pair of identical lever handles from the Josette Rispal-Lejeune donation in 2008 entered the Musée d’Orsay’s collections. The Musée d’Orsay posted photographs of them online, and their description clearly identified them as being by Guimard, although no bibliographical data was provided. Given this information, there seemed to be little doubt that the window handles sold on eBay were indeed by Guimard.

Pair of “lever-shaped door handles,” attributed to Guimard. Dimensions: width 13 cm, height 6 cm. Musée d’Orsay. Inventory numbers AOA 1742 1 and AOA 1742 2.

In addition, the eBay seller specified that his espagnolette locks bear the “FT” mark, which he claimed to be that of the Thiébault (or rather Thiébaut) foundry, a Parisian art foundry that was mainly active in the second half of the 19th century. As a matter of fact, the “FT” mark belongs to the Maison Fontaine, located at 181 rue Saint-Honoré in Paris, which specialized in artistic metalwork. This mark was acquired from Maison Fromentin when its business was bought out.

And the album Le Castel Béranger clearly establishes that Guimard entrusted Maison Fontaine with the production of all the hardware for Castel Béranger, including the lock decorations, landing doorknobs, and door handles. It is therefore reasonable to assume that Guimard remained loyal to Fontaine for this model of espagnolette lock.

Hector Guimard. Landing doorknob, model from the Castel Béranger series produced by Maison Fontaine. Pictured here in the Jassedé building, 142 avenue de Versailles, Paris. Photo private collection

And yet, after consulting several old documents and visiting the charming Fontaine museum in Paris, one quickly becomes convinced of the contrary.

The first of these documents is a catalog from Maison Fontaine, published in August 1900 (no doubt on the occasion of the Paris World Fair) entitled Decorative Locks/Antique Styles/Modern Designs. It presents a large selection of photographic plates where the names of some of Maison Fontaine’s collaborators are mentioned.

Cover of the Maison Fontaine catalog. Decorative locks/Antique styles/Modern designs, August 1900.

Private collection.

The second document is a portfolio, published by Maison Fontaine at an unknown date (probably around 1900). Rather than a commercial document, it is a prestigious publication showcasing some of the company’s most beautiful creations.

Fontaine Portfolio, date of publication unknown. Fontaine Museum.

Fontaine Portfolio, date of publication unknown. Fontaine Museum.

Finally, the albums kept at the Fontaine Museum have a more clearly commercial purpose. They present the items, classified by product type, with their number and dimensions but without the name of their creator or their date of creation.

Indeed, from the first illustrated page (pl. 100) of the August 1900 catalog, the attribution of the espagnolette locks and door handles to Guimard is replaced by Eriksson, who is credited with an espagnolette lock (no. 187, pl. 100), a knob (no. 616, pl. 100), and a lock (no. 214, pl. 100). However, several other items in the catalog that do not bear his name can easily be attributed to him.

Eriksson, appliances produced by Maison Fontaine. Computer graphics montage based on various plates from the Fontaine catalog, August 1900. Private collection.

On plate 317, we find the famous espagnolette lock (no. 230) shown with its upper strike plate, its upper rod guide similar to the ends of the espagnolette casing, and its intermediate rod guide, which echoes the pattern of the ends of the casing and is identical to the espagnolette rod guide. Plate 169 also shows the espagnolette knob, numbered 658.

Eriksson, espagnolette lock no. 658. Fontaine catalog, August 1900, plate 169. Private collection.

Eriksson, espagnolette lock no. 658. Fontaine catalog, August 1900, plate 169. Private collection.

Still by analogy of motifs, we can also attribute to Eriksson: a bolt (no. 178, pl. 100); a latch (no. 131, pl. 100);

Eriksson, bolt n° 131. Catalogue Fontaine, août 1900, pl. 604. Private collection

Eriksson, bolt n° 131. Catalogue Fontaine, août 1900, pl. 604. Private collection

Eriksson, bolt n° 131. Catalogue Fontaine, août 1900, pl. 604. Private collection

Eriksson, bolt n° 131. Catalogue Fontaine, août 1900, pl. 604. Private collection

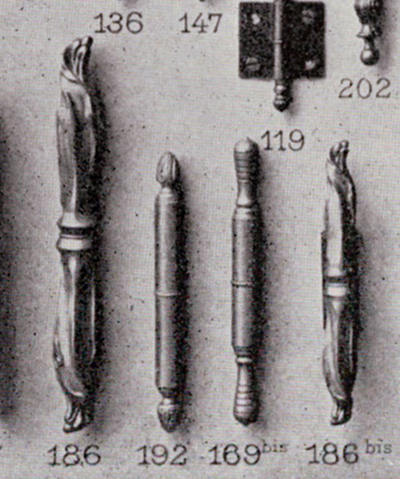

hinges (Nos. 186 and 186 bis, pl. 100 and 427);

Eriksson hinges n° 186 et 186 bis. Catalogue Fontaine, août 1900, pl. 427. Private collection

Eriksson hinges n° 186 et 186 bis. Catalogue Fontaine, août 1900, pl. 427. Private collection

metal decorations on a shelf (no. 704, pl. 100); a lock with a latch (no. 277, pl. 585);

Lock n° 277 from catalogue Fontaine 1900 by Eriksson here with unknown bolts). Priv. Coll.

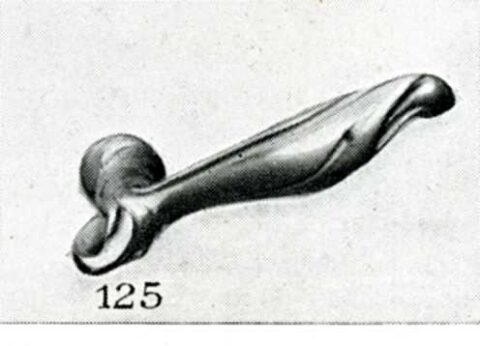

as well as the handle mentioned above. This crutch is available in three widths: 120 mm (No. 125), 130 mm (No. ?), which is the one in the Musée d’Orsay, and 142 mm (No. 314).

Eriksson, handle n° 125. Catalogue Fontaine, August 1900, pl. 134. Private collection

Eriksson, handle n° 125, width 120 mm. Auction Delorme – Collin du Bocage, 20 March 2014, lot 188, brand « F.T ».

Eriksson, handle n° 125, width 120 mm. Auction Delorme – Collin du Bocage, 20 March 2014, lot 188, brand « F.T ».

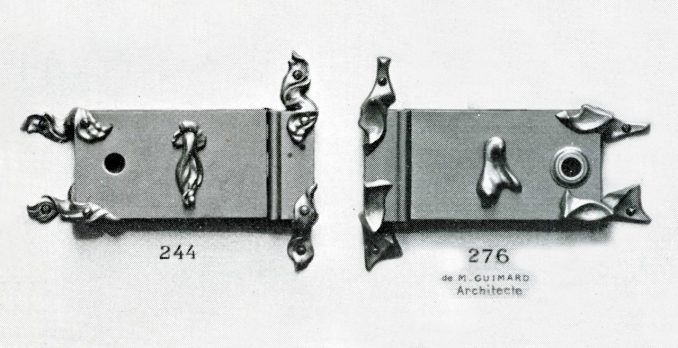

Eriksson, handle no. 314, width 142 mm. Private collection

The Fontaine catalog from August 1900 also features Tony Selmersheim for items that were still relatively unmodern, and Alexandre Charpentier, who incorporated figurative bas-reliefs (similar to those he created in his original profession as a medalist) onto strictly rectangular or octagonal surfaces. Finally, there is mention of “M. Guimard Architecte,” who is credited in this catalog only with a lock decoration (no. 276, pl. 585), that of the Castel Béranger. On the same plate 585, another set of lock decorations (no. 244) is reproduced without mentioning the author but is easily identifiable thanks to the similarity of its lugs to the motifs on Eriksson’s bolt. Its construction is identical to that of Guimard’s no. 276, with a simple parallelepiped box and strike plate featuring no decoration other than the entry cover and the lugs that hold the strike plate and box together at the four corners.

Eriksson for No. 244 and Hector Guimard for No. 276, lock models published by Maison Fontaine. Computer-generated image based on plate 585 of the Fontaine catalog, August 1900. Private collection.

Eriksson for No. 244 and Hector Guimard for No. 276, lock models published by Maison Fontaine. Computer-generated image based on plate 585 of the Fontaine catalog, August 1900. Private collection.

Guimard opted for a fairly simple and straightforward modeling of the elements, where you can see the modeler’s thumbprint, while Eriksson remained faithful to a more detailed decorative style.

Guimard, lock brackets, no. 276 in the Fontaine catalog, August 1900. Private collection.

Guimard, lock brackets, no. 276 in the Fontaine catalog, August 1900. Private collection.

Although an entire page in the Fontaine portfolio (a prestigious document, not a commercial one) is devoted to Guimard’s designs for the Castel Béranger, his models do not appear in the Fontaine museum’s albums and are not kept in the Fontaine house collections. It is therefore likely that, apart from the lock, Guimard, who had already published them in 1898 in the Album of Castel Béranger, wished to retain exclusivity over them.

But who is this Eriksson who seems to have left so few traces in French decorative art? He is the Swedish sculptor Christian Eriksson (Taresud, 1858—Stockholm, 1935), famous in his own country and internationally trained. Nine years older than Guimard, he attended the same Parisian art schools as him during the same years. Our Swiss correspondent Michel Langenstein provided us with a biographical note from the catalog published in 2008 by The Dansk Museum of Art & Design in Copenhagen. It significantly enriches the one from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. We also drew information from his Wikipedia entry published in Swedish.

Christian Eriksson. Silver jewelry box depicting a little girl immersing herself in a basin that she causes to overflow, framed by a male figure and a female figure. 1897. Dimensions: width 6.5 inches, depth 2.8 inches, height 3.7 inches. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston., Boston.

Christian Eriksson. Silver jewelry box depicting a little girl immersing herself in a basin that she causes to overflow, framed by a male figure and a female figure. 1897. Dimensions: width 6.5 inches, depth 2.8 inches, height 3.7 inches. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston., Boston.

Christian Eriksson was born in Taresud in the county of Värmland, Sweden, in an environment devoted to agriculture and woodworking. As a child, he worked with his father, cabinetmaker Erik Olson, and his brother Elis Eriksson, who would also become a cabinetmaker. As a young man, he apprenticed with an ornamentalist in Stockholm while attending technical school. From 1877 to 1883, he worked as a furniture designer and model maker in a factory in Hamburg, where he also attended a school of crafts and design. In 1883, he traveled, working in various workshops in the Rhineland before ending up in Paris, where he enrolled at the École des Arts Décoratifs, then at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1884, in the studio of sculptor Alexandre Falguière. In 1886, he made his debut at the Salon and became known in 1888 with the sculpture Le Martyr, which earned him a medal and a scholarship. He also received commissions for furniture, built a house in Taresud, the town of his childhood, while traveling frequently between Paris and Värmland from 1894 (the date of his marriage to the Frenchwoman Jeanne Tramcourt) to 1898, finally settling in Stockholm. In 1902, he tackled the theme of Sami culture for the first time with the sculpture The Lapp.

Christian Eriksson. Seated Lapp, 1909. Bukowskis auction, Stockholm.

Christian Eriksson. Seated Lapp, 1909. Bukowskis auction, Stockholm.

From 1903 to 1908, he was responsible for the decoration of the façade of the Royal Dramatic Theater in Stockholm.

Christian Eriksson, photographic portrait, from 1904. Illustration taken from the Wikipedia entry on Eriksson.

Christian Eriksson, photographic portrait, from 1904. Illustration taken from the Wikipedia entry on Eriksson.

Having thus experienced the early years of French Art Nouveau, practicing monumental sculpture as well as decorative art with small bronze and silver vases and bowls, he did not disdain offering his assistance to industrial artists, notably through his important collaboration with Maison Fontaine’s “modern experiments.” His more familiar figurative style appears on several pieces of hardware, such as lock no. 214.

Christian Eriksson, lock no. 214, La Curiosité, with handle no. 125. Fontaine Museum.

Christian Eriksson, lock no. 214, La Curiosité, with handle no. 125. Fontaine Museum.

Christian Eriksson, lock no. 214, La Curiosité, with handle no. 314. Private collection.

Christian Eriksson, lock no. 214, La Curiosité, with handle no. 314. Private collection.

The female figure who appears to be peering through the keyhole earned her the name La Curiosité (Curiosity) and links her to the late Symbolist movement, much like the door handle/mailbox La Renommée (Fame) designed by Victor Prouvé for the door of the Nancy carpenter Eugène Vallin’s house in 1895.

Eriksson, lock no. 214, La Curiosité (detail). Private collection.

Eriksson, lock no. 214, La Curiosité (detail). Private collection.

As a sign of its importance, it occupies a page in the Fontaine portfolio.

Christian Eriksson, lock no. 214 with handle no. 125. Labeled “La Curiosité” (Curiosity); Artistic lock designed by Eriksson — Salon du Champ de Mars. Plate from the Fontaine portfolio, date unknown. Fontaine Museum.

Christian Eriksson, lock no. 214 with handle no. 125. Labeled “La Curiosité” (Curiosity); Artistic lock designed by Eriksson — Salon du Champ de Mars. Plate from the Fontaine portfolio, date unknown. Fontaine Museum.

The right side of the lock, with the handle, can be found on the doors of two of the three salons created by Nancy-born Louis Majorelle for the Café de Paris (41 avenue de l’Opéra) in 1898, which helps to pinpoint its date of creation. The following year, when Henri Sauvage was commissioned to design two additional salons, he used more commonplace locks that were less well integrated into the woodwork.

Door to one of the three salons furnished and decorated by Louis Majorelle at the Café de Paris, Avenue de l’Opéra in Paris, in 1898. The door is secured by Eriksson’s Fontaine lock no. 214. German portfolio Modern Bautishler-Arbeiten, pl. 53, August 1902.

Door to one of the three salons furnished and decorated by Louis Majorelle at the Café de Paris, Avenue de l’Opéra in Paris, in 1898. The door is secured by Eriksson’s Fontaine lock no. 214. German portfolio Modern Bautishler-Arbeiten, pl. 53, August 1902.

At the 1900 World’s Exhibition, this lock, No. 214, La Curiosité, was presented with knob No. 616 (Woman Combing Her Hair) by Maison Fontaine, alongside figurative works by Gustave Michel and Louis Bigaux. The Museum of Art and Design in Copenhagen has a silver version of this knob.

Eriksson, door knob n° 616. Catalogue Fontaine, August 1900, pl. 169. Private collection

Eriksson, door knob n° 616. Catalogue Fontaine, August 1900, pl. 169. Private collection

C

Christian Eriksson, doorknob n°° 616, Femme se coiffant, bronze with traces of gold. Private collection

The handle of espagnolette No. 187 is quite astonishing. Seen from a distance, it is reminiscent of the end of a bone and, by extension, the sarcasm of art critic Arsène Alexandre in Le Figaro on September 1, 1900, who claimed that “the noodle [had] compromised itself with a sheep bone to compose what has been given the generic and bizarre name of “Art Nouveau””

Eriksson, espagnolette n° 187. Portfolio Fontaine, unknown date. Musée Fontaine.

Eriksson, espagnolette n° 187. Portfolio Fontaine, unknown date. Musée Fontaine.

But upon closer inspection of its end, we see that it is a small figure that seems to be using all its weight to keep it closed.

Eriksson, espagnolette no. 187 (detail of the handle). Fontaine Museum.

Eriksson, espagnolette no. 187 (detail of the handle). Fontaine Museum.

On the other hand, the hinges, bolt, espagnolette lock and rod guides are closer to the naturalistic style of Art Nouveau, evoking curled leaves.

Christian Eriksson, strike plate and guide for espagnolette bolt no. 230. Fontaine catalog, August 1900, plate 317.

Christian Eriksson, strike plate and guide for espagnolette bolt no. 230. Fontaine catalog, August 1900, plate 317.

But as we mentioned above, the details of the espagnolette bolt and of the handle introduce a whole new approach that emphasizes the modeler’s technique, deliberately displaying an unfinished look. There is a real parallel here with the work of Guimard’s early years, whose modeling had a “crumpled” and somewhat wild appearance before he quickly moved on to emphasize the harmony of lines and the elegance of composition.

Finally, thanks to our German correspondent Michael Schrader, who kindly reminded us, we should mention the presence of Eriksson espagnolettes on the windows of the beautiful reception hall of the town hall in Euville in Meuse, decorated (or rather clad internally) in 1907 by Eugène Vallin. The designer of several models of hardware for his joinery and furniture, Vallin did not have his own model of espagnolette. In this case, he therefore resorted to the catalogs of Parisian manufacturers.

Espagnolette by Christian Eriksson on a window in the village hall of Euville Town Hall. Installed in 1907 by Nancy carpenter Eugène Vallin. Photo by Cédric Amey. Nancy-guide.net.

Espagnolette by Christian Eriksson on a window in the village hall of Euville Town Hall. Installed in 1907 by Nancy carpenter Eugène Vallin. Photo by Cédric Amey. Nancy-guide.net.

Frédéric Descouturelle

with the collaboration of Dominique Magdelaine and Olivier Pons.

Many thanks to the collectors who allowed us to reproduce their objects and provided information, as well as to Ms Christine Soulier, Head of Decorative Locksmithing at Maison Fontaine.

P.S. At the same time as this article was published, the Musée d’Orsay amended its entry to restore Eriksson’s authorship of his two handles: http://www.musee-orsay.fr/fr/collections/catalogue-des-oeuvres/resultat-collection.html?no_cache=1 Click on ‘Collection’, then ‘Catalogue of works’, then type ‘Eriksson’.

Translation: Alan Bryden