A rare crystal vase by Guimard

22 May, 2025

Tracked for years, this exceptional vase has recently been added to the collections of our partner for the Guimard Museum project. Lengthy negotiations led to the acquisition of this rare object, the first of its kind to be identified and described. Unlike other areas of decorative arts where Guimard was prolific, he produced very little glassware.

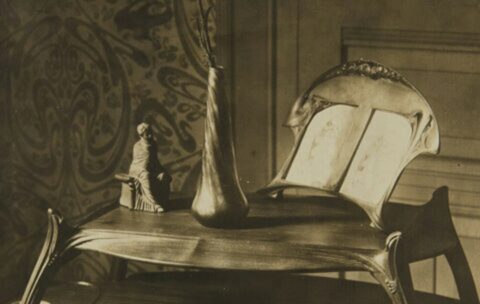

Guimard vase from the Cristallerie de Pantin, height: 40.2 cm, outer diameter at the opening: 5.2 mm, outer diameter at the base: 12.7 cm, weight: 1.437 kg. Private collection. Photo F. D.

The overall shape is fairly common for Art Nouveau glassware, resembling a “bottle vase” that can be divided into three parts: a very flat base highlighted by a protrusion, a slightly conical body, and a narrowing at the top before the opening curves outward. This shape, with its swirling ribs, seems to be unique to Guimard, who did not attempt to reproduce the silhouettes of his designs for bronze or ceramics. But as we shall see later, are we sure that Guimard is the creator of this shape?

This vase remained in the seller’s family for a long time, but it has not been possible to ascertain the original conditions of purchase. It is in good condition, despite a few scratches and a slight limescale deposit showing that it was once used as a flower vase.

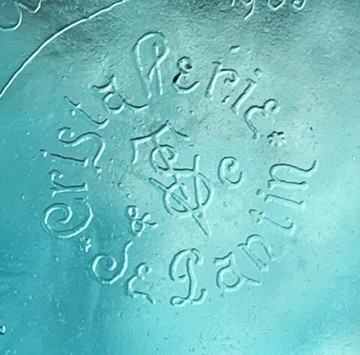

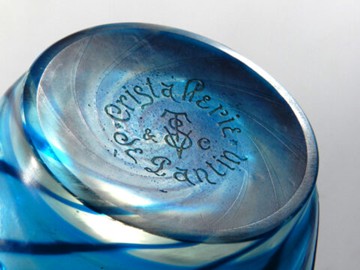

It was produced at the Cristallerie de Pantin[1], as indicated by the signature engraved on its base, around the “STV” logo, which stands for the initials of the crystal factory’s full name: Stumpf, Touvier, Viollet & Cie.

Signature of Cristallerie de Pantin on the base of the vase. Private collection. Photo Justine Posalski.

Measuring 40.2 cm high and weighing 1.437 kg, it has a volume of 0.480 liters. These last two figures can be used to calculate its density: 2.99, very close to that of classic lead crystal (3.1).

Calculation of the volume of the Guimard vase from the Cristallerie de Pantin. Private collection. Photo Fabien Choné.

The question of the exact nature of the material arose, even though the vase came from a crystal factory, because we established that the glass shades of the candelabra in the subway entrances produced by the same factory from 1901 onwards were made of glass without any added lead. The Cercle Guimard recently purchased one copy.

Glass shade of a Guimard metro candelabra. Collection of Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

The base of the vase also bears Guimard’s handwritten, curved signature. It is characterized by the continuity of the design in a single line joining the first and last names and ending with a long initial that returns emphasizing them. It should be noted that the execution at the tip is slightly more hesitant than that of the crystal factory logo, for which the worker assigned to this repetitive task had a stencil.

Guimard’s signature on the base of a vase from the Cristallerie de Pantin. Photo Justine Posalski

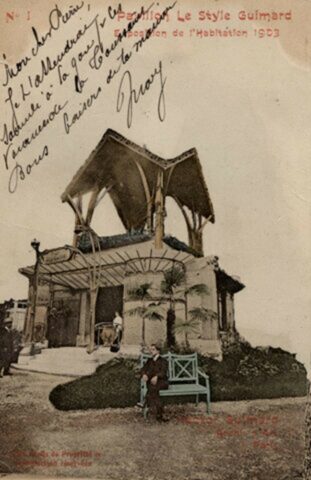

The “Le Style Guimard” pavilion at the Housing Exhibition at the Grand Palais in 1903. Vintage postcard no. 1 from the Le Style Guimard series. Private collection.

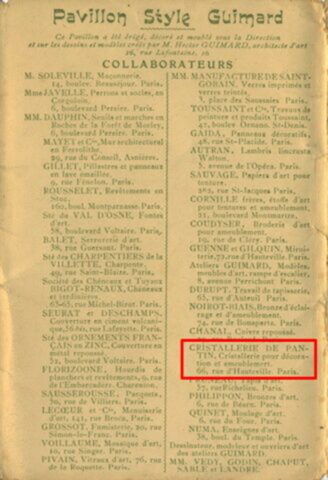

In the list of contributors included in the brochure accompanying the series of postcards, mention is made of the Cristallerie de Pantin, located at 66 rue d’Hauteville, where their Paris store was located.

Partial view of the packaging insert for the Le Style Guimard series of postcards. Private collection.

The crystal factory was included in this list of collaborators, certainly for the glass shades of the metro entrance that framed the entrance to Guimard’s pavilion, and possibly also for another product on display: probably vases, as suggested by the description that Guimard associated with the supplier’s name: “crystalware for decoration and furnishings.” Unfortunately, the views of the interior of the pavilion that we have do not show these vases. Moreover, there is no indication that the crystalware presented in the pavilion at that time was already the result of a collaboration between the architect and the Cristallerie de Pantin. Guimard may simply have chosen products from the glassworks’ catalog to decorate the furniture on display. The following year, however, we became certain that this collaboration had indeed taken place. In the booklet that Guimard published for the 1904 Salon d’Automne, he detailed his shipment by category. Number 4 of the “Objets d’art Style Guimard” is described as follows: “Guimard-style vase in aquamarine crystal. Price: 65 francs.“

The name ”aquamarine” was not invented by Guimard, who instead incorporated it into a production line of the Cristallerie de Pantin that had started a few years earlier. It refers, of course, to the name of the gemstone, a variety of beryl with a light blue color reminiscent of the sea. These bluish shades, which are difficult to achieve, were sought after empirically by various French crystal manufacturers. Émile Gallé in Nancy, for example, used cobalt monoxide to obtain a very light blue color called “moonlight,” which was unveiled at the 1878 World’s Fair. At the Cristallerie de Pantin, to obtain a slightly opaque glass with intermediate turquoise iridescence, the yellow of uranium dioxide and the green of a chromium oxide were mixed with cobalt blue.

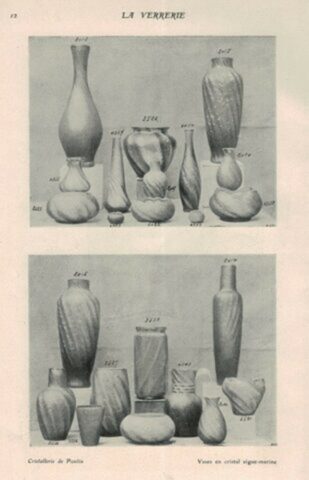

The first mention of the production of “aquamarine” crystals by the Cristallerie de Pantin that we know of appeared on a page of the Maison Moderne catalog[2] published in 1901.

Documents on « l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle » (catalogue of La Maison Moderne), Paris, Edition de La Maison Moderne, 1901, p. 12, “Crisallerie de Pantin/Vases en cristal aigue-marine.” Private collection.

In the two photographs on this page, twenty-two vases of different shapes and a colors that can only be described as bluish all feature swirling ribs, often regularly punctuated with reliefs like the surfaces of shells, another way of recalling the marine inspiration of the series. The creator or creators of these modern shapes are not mentioned, suggesting that they were probably employees of the crystal factory[3].

Guimard’s crystal vase was not completely unknown to us, as documents from the Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard donation kept at the Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs identify at least two examples decorating a piece of furniture probably presented at the Salon d’Automne.

Coll. Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs, donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Within the same collection of documents, another twisted vase model, with a more pear-shaped base and a more tapered neck, is very similar to No. 4357 on the page of the Maison Moderne catalog (see above). However, Guimard’s involvement in this piece has not been confirmed.

Coll. Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs, donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Another example of a vase that could have come from the Cristallerie de Pantin is the translucent crystal model displayed in the showcase of the grand salon at the Hôtel Guimard, which features the same type of twists.

Detail of the window display in the grand salon of the Guimard Hotel.

Private collection.

It should be noted that none of these vases feature any added floral decoration imitating the style of Gallé and Daum glassware from Nancy. This may have been a specific request from Maison Moderne, which wanted a more understated design in keeping with the Belgian style championed by Van de Velde. Outside of Maison Moderne, Cristallerie de Pantin produced numerous models of “aquamarine” vases with floral decoration, which occasionally appear on the art market.

Aquamarine vase with floral decoration engraved with acid from Cristallerie de Pantin, online gallery les_styles_modernes, sold on eBay Netherlands, May 2025, height 24.8 cm, diameter 10.3 cm, weight 796 g. Photo les_styles_modernes, rights reserved.

Aquamarine vase with floral decoration engraved with acid from Cristallerie de Pantin, online gallery les_styles_modernes, sold on eBay Netherlands, May 2025, height 24.8 cm, diameter 10.3 cm, weight 796 g. Photo les_styles_modernes, rights reserved.

Like these vases, Guimard’s vase also features an acid-etched decoration, but one that is unique to him and reflects his efforts to renew his semi-abstract style, gradually moving away from the harmonious arrangements of curved or whimsical lines that characterized his work around 1900.

Detail of the decoration on the Guimard vase from the Cristallerie de Pantin. Private collection. Photo F. D.

Once again, it is not easy to describe or interpret this design, which leaves the observer’s imagination free to find its own references. While a plant-inspired motif seems to be ever-present, with highly stylized stems and flowers repeated ten times around the circumference, a motif inspired by the treble clef is not impossible.

Detail of the decoration on the Guimard vase from the Cristallerie de Pantin. Private collection. Photo F. D.

Some of the undated watercolor drawings of frieze designs donated by his widow Adeline Oppenheim to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs show some stylistic similarities.

Guimard, detail of a design for a frieze, watercolor on paper. Collection of the Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs, donation of Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Other elements of the decoration, such as the blue lines and the yellow coloring at the top, allow us to speculate on how the vase was made. As with any glassmaking process, the glassmaker would have taken a parison from the furnace using his hollow rod and given it an initial shape by blowing and swaying it. He then rolls the parison on the “marble” (a polished cast iron table) to add calcined bone powder and arsenates, which have been placed there beforehand and which will give the glass a satin appearance over the entire height of the vessel and a yellow coloration in its upper quarter. In addition, twisted blue threads, visible at the top and bottom of the vase, were prepared in advance, laid down and then covered with a new layer of glass, which was returned to the furnace. This is therefore an intercalated decoration and not the usual Venetian thread technique, where the threads are applied to the surface.

Guimard vase neck from the Cristallerie de Pantin with blue intercalated fillets. Private collection. Photo F. D.

Base of the Guimard vase from the Cristallerie de Pantin with blue intercalated strips. Private collection. Photo F. D.

With the glass vessel still at the end of the rod (on the side of the future opening), the base is roughly shaped by gravity and tapping against the marble. It is then placed in the clamshell mold and blown so that it sticks to the walls. This is when most of the swirling relief is created. Once the mold is opened, the vessel is picked up under the base using a small amount of molten glass at the end of an iron rod (the pontil). On the opposite side, the neck is twisted (as evidenced by the arrangement of the air bubbles that follow this movement) before being detached from the rod by cutting it with scissors and shaping it with pliers.

Guimard vase neck from the Cristallerie de Pantin. Private collection. Photo Justine Posalski.

After cooling slightly to ensure stability, the vessel is coated with a thin layer of a more intense blue glass, which the glassmaker takes from a second furnace. The vase is then detached from the pontil, which leaves a scar under the base. After gradual cooling, the blue glass coating on the surface is treated with hydrofluoric acid. To reveal the decoration that will be preserved in blue, the surface is first protected with a varnish (at that time, Judea bitumen), while the unprotected surfaces are removed with acid until the underlying glass appears. Under the base, the trace of the pontil is removed by grinding and polishing so that the crystal manufacturer’s logo and Guimard’s signature can be engraved, as we saw above. However, around the opening, the remaining surface irregularities show that the glass has not been reworked by grinding.

Guimard vase neck from the Cristallerie de Pantin. Private collection. Photo F. D.

The main reason why this vase came to the attention of Guimard specialists so late was its rarity. Its imperfect execution, particularly evident in its fairly substantial bubbling, suggests that it was part of a very small series. The other reason is that its attribution to Guimard is not obvious at first glance. It is even likely that, in the absence of a signature[4] and despite its abstract naturalistic decoration, this vase would not have aroused the same interest on our part, nor would it have prompted the research that followed to find the rare clues that enabled us to locate it within Guimard’s works. At the same time as he wanted to simplify the Guimard style by reducing it to a simple decoration on an object that could ultimately be adapted to all styles of interior design, it is quite likely that Guimard also chose a vase shape that already existed at the Cristallerie de Pantin — a shape that was not necessarily already on the market — and “Guimardized” it, thereby replicating the same approach he took with products from certain other manufacturers, as we have demonstrated for the stoneware vases produced by Gilardoni & Brault[5].

Frédéric Descouturelle and Olivier Pons,

with the assistance of Justine Posalski and Georges Barbier-Ludwig.

Notes

[1] The crystal factory was founded in 1847 at 84 Rue de Paris in Pantin and taken over in 1859 by E. Monot, a former worker at the Lyon crystal factory. It quickly prospered, becoming the fifth largest crystal factory in France and then, after the 1870 war (and the transfer of the Saint-Louis crystal factory to German territory), the third largest (after Baccarat and Clichy). The crystal factory industrially manufactured a complete range of products, which it displayed in its Paris store on Rue de Paradis. Its warehouse was also in Paris, at 66 Rue d’Hauteville. The company name changed several times: “Monot et Cie,” then “Monot Père et Fils et Stumpf,” and finally “Stumpf, Touvier, Viollet & Cie” after Monot withdrew in 1889. It was absorbed in 1919 by the Legras glassworks (Saint-Denis and Pantin Quatre-Chemins).

[2] Founded by art critic Julius Meier-Graefe at the end of 1899, this gallery dedicated to modern decorative art competed with the better-known L’Art Nouveau gallery owned by Siegfried Bing. Two articles by Bertrand Mothes will be published on this subject shortly. [3] For other products, the catalog lists the names of the designers.In this case, it is likely that the contract between the gallery and the designer specified that the latter’s name had to be mentioned.

[4] Another example of this vase has been catalogued and appears in the book “Le génie verrier de l’Europe” (G. Cappa, ed. Mardaga, 1998). Unlike our vase, which is predominantly aquamarine in color, this one is characterized by colorless crystal with a gradient of metallic tones, with the “rosathea” and “yellow” shades predominating, while the aquamarine tone is concentrated in the lower third. As this piece is unsigned, it may be a prototype.

[5] See our article on the “guimardization” of stoneware vases produced by Gilardoni & Brault.

Translation: Alan Bryden