A Guimard’s metro signaling glass (“verrine”) for our museum project

( Note: in this article, the term “signaling glass” is used to translate the French “verrine”, meaning the protective cover of the lamp in a Guimard Metro candelabra)

If you could not attend our last Annual General Meeting, you may not have been able to see – or touch – our latest purchase: a Guimard metro candelabra signaling glass produced by the Cristallerie de Pantin. In a recent article, we corrected our earlier opinion [1] by admitting, with supporting evidence, that these signaling glasses were originally white, and that the change to an orange-red color took place around 1907, four years after Guimard’s collaboration with CMP (Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris) came to an end.

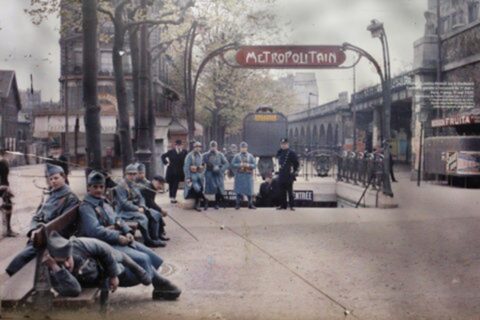

We would point out, however, that it was likely that red signaling glasses existed at an early date, since the detail of a black-and-white photograph of the uncovered surround of Rome station, taken in 1903 shortly after its installation, is more compatible with a red color than a white one.

Rome station open surround (detail), installed in 1902. Photo Charles Maindron (1861-1940) CMP photographer. Silver chloride gelatin print developed on June 5, 1903. École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, Direction de la documentation, des archives et du patrimoine.

On the contrary, white glass was used for at least one of the last surviving shield surrounds, installed at Porte d’Auteuil station in 1913.

Surround of the Porte d’Auteuil station. Photo Heinrich Stürzl, based on an autochrome plate by Frédéric Gadmer, taken May 1, 1920. Musée départemental Albert-Kahn collection (inv. A 21 126). Source Wikimedia Commons.

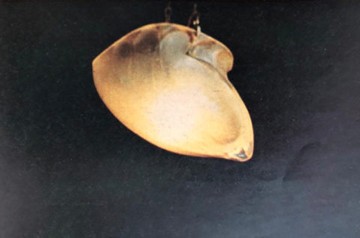

At least one of these white signaling glasses still exists in a private collection, as we know it from a detailed photograph [2] taken in 1967.

White glass used as a chandelier. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulme (detail). Cercle Guimard archives and documentation center.

A total of 103 open shield surrounds were installed between 1900 and 1913. One of these had already been dismantled in 1908, leaving 102 on the eve of the First World War. At a rate of two signaling glasses per surround, there were therefore 204 signaling glasses on the network at that time. Subsequently, the number of signaling glasses fell considerably because of the many dismantling operations that took place until 1978, when all the Guimard entrances were finally classified. At that date, there were still 60 uncovered entourages with shields. Logically, in the interest of optimal material management, the removed signaling glasses of the surrounds should have been stored, but we don’t know what happened to them.

As for the remaining signaling glasses on the network, whether red or white, they were all replaced by synthetic equivalents, probably in the 70s [3]. The motivation for this exchange can easily be guessed. It wasn’t a question of protection against vandalism, which was still in its infancy [4], but simply a maintenance constraint. These rather heavy glass vessels had to be handled when a lamp had to be replaced. This rather delicate handling, repeated dozens of times, led to numerous accidents on the necks of the signaling glasses and sometimes to their destruction. What’s more, the Pantin crystal glassworks had probably stopped producing new pieces a long time ago, so RATP was no longer able to renew them. The RATP therefore decided to replace them with copies made of synthetic material, which were lighter and less fragile, but far less beautiful. In the process, it dismantled at least a hundred signaling glasses, which should also have been put into storage.

Plastic signaling lamp cover Coll. Hector Guimard diffusion. Photo F. D.

By 2000, however, R.A.T.P. no longer owned a single one. What had happened? Unfortunately, the certainty that these signaling glasses would no longer be used on the network meant that this stock was probably managed in a less than rigorous manner. The lack of interest in, or even disdain for, the Art Nouveau style for many years meant that they had neither the artistic nor the financial value that would have encouraged R.A.T.P.’s management to preserve them. At the same time, however, private collections were being made, either out of aesthetic interest and without the feeling of committing a criminal act, or out of greed, since as early as the 1980s, Guimard metro pieces were being smuggled out of France, notably to make bronze copies for sale in the United States [5]. Authentic signaling glasses were found on at least one bronze subway surround in Houston.

Fortunately, before it no longer owned any, R.A.T.P. had, this time officially, loaned or donated signaling glasses along with complete surrounds, notably to the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1958, the Staatliches Museum für Angewandte Kunst in Munich in 1960, the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris in 1961 (transferred to the Musée d’Orsay) and then to the Montreal metro company in 1966. During the restoration of the latter, the STP subway company also disassembled its signaling glasses, giving one back to the RATP in 2003 [6].

On September 4, 2003, Mrs Anne-Marie Idrac, President of RATP, receives from Mr Claude Dauphin, Chairman of the STM’s Board of Directors, one of the two vintage signaling glasses from the surround shipped to Montreal in 1966. Photo coll. STM

We concluded our previous article on the color of signaling glasses by prophesying that such glasses would inevitably reappear as the generations of their private owners changed. And this is precisely what happened: in October 2024, a few months after the publication of our article on glassware colors, one of our faithful correspondents — half-serious, half-amused — alerted us to the publication on a well-known free classified ads site of a proposal to sell the end of a subway candelabra with its glassware.

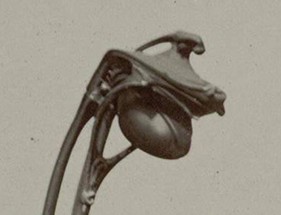

Photo provided by the seller of the Guimard metro candelabra end for a sale ad posted on the Le Bon Coin website.

We immediately got in touch with the advertiser, who confirmed that it was cast iron (not bronze) and that the signaling glass was indeed made of glass. Given the rarity and interest of such an object, we quickly agreed on a price with the seller, and a family friend immediately dismantled it and put it in a safe place until it could be shipped to the Paris region.

End of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

As we had expected, the discussion with the vendor revealed that its owner (who had recently passed away) had held a fairly senior position in the RATP maintenance hierarchy, and that upon his retirement in the mid-80s, he had been given an entire metro lamp post. However, the size and weight of such an object made it very difficult to handle and use, so the happy new owner decided to saw off the end for outdoor use on his holiday home in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques region, where he was originally from. The remaining part rusted away for a few years outdoors in the Paris region, before being sold for its weight in metal.

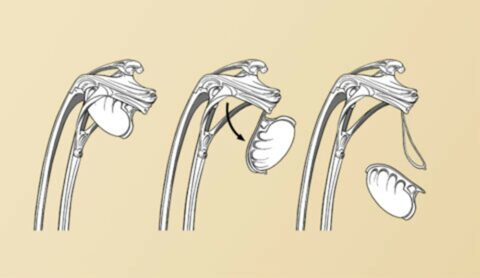

Once the end of the candelabra had been recovered, we separated it from its sheet metal support. The signaling glasses had previously been removed from its housing. To do this, it was necessary to remove the cross-pin (held in place by a chain) which held the collar in place at the back.

End of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

The collar, held at the front by a hinge, can then be tilted to release the signaling glasses.

End of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

Disassemble the signaling glass by unlocking the collar. Drawing F. D.

The post of the candelabra has been cut away, revealing the hole through which the lamp’s power supply passes.

End of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

The signaling glass was simply cleaned with soapy water, pending a more thorough cleaning. As we feared, its neck shows a lot of missing parts due to handling during lamp changes.

Signaling glass of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

Weighing 6.5 kg, it measures 40 cm in overall length and 24 cm in height. Its maximum width is 26 cm, less than it should be (28 cm) due to the missing collar. The opening measures 26 cm by 20 cm.

Signaling glass of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

Nevertheless, most of the signaling glass is in excellent condition and, with the difference that its neck is more uneven, our glass is identical to that of the RATP: same clean lines, satin-finish surface and color that varies according to the lighting and thickness of the glass, from dark red to light orange.

Signaling glass of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

A piece of old glass sent to us by the seller shows that the glass is colored in the mass and not plated on the surface.

Edge of a shard from the neck of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

The fact that the signaling glasses were made in a crystal factory and not in a glass factory raised a question: was the material crystal or indeed glass? The shard above gave us an easy answer. Its weight is 8 g and its volume (obtained by dipping it into a graduated tube and measuring the rise in water level) is 3 ml, giving a density of 8/3 = 2.6, that of glass (that of crystal being 3.85).

Measuring the volume of the shard of the signaling glass in a graduated tube. Photo M.-C. C.

Let’s recall the manufacturing process for this signaling glass as carried out by the Cristallerie de Pantin. A bivalve mold is used, articulated around its sagittal axis and based on a plaster model supplied by Guimard. To obtain the correct “point”, the glassmaker places a pellet of molten glass at the bottom of the mold. The gob of glass (the volume of glass picked from the jar at the end of the cane) is shaped by balancing and shaping, then introduced into the mold. A layer of about 8 mm of glass is then pressed onto the inner surface of the mold by air blown into the cane. The mold is then opened and the glass vessel cut with scissors to expose the wide opening. The edges are bent with pliers and probably shaped by applying another mold around the opening. After cooling, any imperfections and seams caused by the mold joints are carefully ground away. Finally, the outer surface of the signaling glass is acid-etched.

Signaling glass of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

The aspect of this signaling glass has not failed to elicit comparisons with well-known shapes: teardrop, fruit, frog’s eye. One of the most disparaging comparisons, “half-sucked candy” [7], is not the most inaccurate. It’s not impossible that Guimard’s illustrative intent was to evoke a flame, as if spat from the end of candelabras. But now that we know that the first signaling glasses were white, this hypothesis seems less credible. It also seems possible that Guimard wanted to capture the look and workings of molten matter, with the signaling glass appearing to be both blown and then pinched at the end and stretched (this action being reflected in the wide striations around the neck). The idea of evoking a downward flow of viscous matter is also admissible, as Guimard was able to illustrate it, notably on the low-end posts of the secondary surrounds. As is often the case in his art of semi-abstract drawing and modeling, many interpretations are relevant, and everyone is free to formulate their own.

The Cercle Guimard was delighted to acquire this candelabra end piece and its signaling glass. It will of course be one of the centerpieces of the section devoted to the Paris metro in our museum project at the Hôtel Mezzara.

Frédéric Descouturelle

Notes

[1] Descouturelle, Mignard, Rodriguez, Le Métropolitain de Guimard, éditions Somogy, 2003; Descouturelle, Mignard, Rodriguez, Guimard L’Art nouveau du métro, éditions La Vie du Rail, 2012. [2] As announced in our previous article, we will one day devote a special article to the astonishing batch of photographs of which it is a part. [3] We give this very approximate date as a matter of conjecture. When writing the books on Guimard’s metro, we were unable to discover the exact date of this replacement. [4] Unfortunately, at present, the reinstallation of signaling glasses, which are easy and very expensive targets, seems to us to be completely unrealistic. [5] See our articles on this subject: “The epidemic of fake bronze subway surrounds in the United States”: part one; the epidemic…part two; The epidemic…part three. [6] The other signaling glass was entrusted to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. [7] Quoted without reference by R.-H. Guerrand in Mémoires du métro, 1961. The article or book from which this quotation is taken has not yet been found.

Translation: Alan Bryden