Month: July 2025

Signing of the long-term lease commitment for the Mezzara Hotel

28 July 2025

On the morning of July 25, the Mezzara Hotel briefly reopened its doors for the signing of the 50-year lease commitment, in the presence of the Minister for Culture Ms. Rachida Dati and numerous other dignitaries.

Welcome for Ms. Dati by Nicolas Horiot, president of the Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

After a brief visit and speeches by Fabien Choné, President of the Fabelsi Holding company, and Ms. Dati, who emphasized the importance of promoting heritage in a dynamic way rather than waiting until it is in danger, highlighting the unusual approach taken jointly by a private entrepreneur and an association of art historians, the official signing took place in the dining room.

Speech by Fabien Choné. Photo D. M.

Signing of the lease commitment Photo D. M.

This morning was an opportunity for the Cercle Guimard and Fabien Choné to reconnect with many of the people who support us and with whom we are developing our museum project. This ceremony was just one step in a process that should continue with a building permit, which will determine when restoration and renovation of the building can actually begin.

The signing of the lease commitment for the Hôtel Mezzara was widely reported in the media, from social networks to icibeyrouth.com and the local press in Saint-Dizier, demonstrating enthusiasm that extends far beyond specialized circles and national borders.

Le Cercle Guimard

The « Maison Moderne » of Julius Meier-Graefe — Part 2

7 July 2025

Organization, offerings, and operation of La Maison Moderne

Among all the artists selected, two Belgian compatriots were given the most important assignment: Georges Lemmen, first and foremost. Meier-Graefe entrusted him with the task of designing the most recognizable element of the brand: its logo. This symbol, intended to be the “brand” of La Maison Moderne, consisted simply of the initial letters of the gallery’s name superimposed on each other, drawn in curves in line with the style already used by Lemmen in the posters for Dekorative Kunst. Simple in design, this logo appeared on most of La Maison Moderne’s production and publications, in its original or a more elaborate form.

Georges Lemmen, logo of La Maison Moderne, 1899.

The design of La Maison Moderne was commissioned to the artist Meier-Graefe trusted most: Henry Van de Velde. He designed a storefront with display windows, allowing passersby to see a selection of the items sold inside.

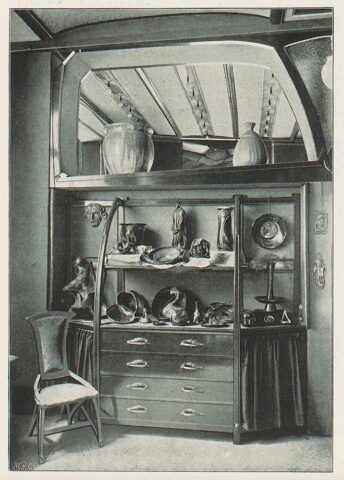

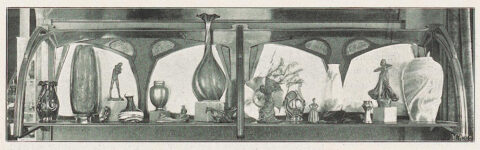

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg. On the shelf of the display cabinet are two vases by Dufrène and Dalpayrat.

Maurice Dufrène, designer, Dalpayrat and Lesbros, ceramist, flamed stoneware, c. 1899, purchased by the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs at La Maison Moderne in 1899, silver mount by Cardeilhac added in 1900, exhibited at the UCAD pavilion at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1900, Musée des Arts Décoratifs. All rights reserved.

The typography for the letters was designed by Georges Lemmen[2]. This choice reflects Meier-Graefe’s confidence in the talent of the two Belgian artists, as the shop front played as important a role as a poster for shops at the end of the 19th century. In the gallery, Van de Velde proposed a complete decor, alternating display cases, shelves, and furnished rooms.

The other artists selected to appear in the gallery catalog were countless: more than sixty were listed. Despite Meier-Graefe’s stated desire to create a gallery that favored French works, foreign artists were very numerous within its walls.

Bernhard Hoetger (Hörde, Germany, 1874 – Beatenberg, Switzerland, 1949), The Storm, c. 1901, bronze, Musée d’Orsay, RF 4189, height 0.311 m, width 0.245 m, depth 0.25 m. All rights reserved. This sculpture is reproduced in Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, bronze 3322-1, La Sculpture p. 5.

To provide an overview of the diversity of the offerings, it is worth mentioning all the nationalities represented among La Maison Moderne’s collaborators: French, Belgian, German, Italian, Austrian, Hungarian, Romanian, Serbian, Danish, Dutch, and Finnish. It is interesting to note the absence of British and Spanish artists among them. Meier-Graefe’s taste is the only real common denominator among all these artists, and they were selected with a concern for consistency that was dear to him (Bing had been criticized for a lack of consistency four years earlier).

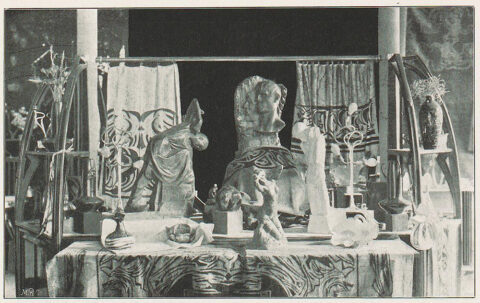

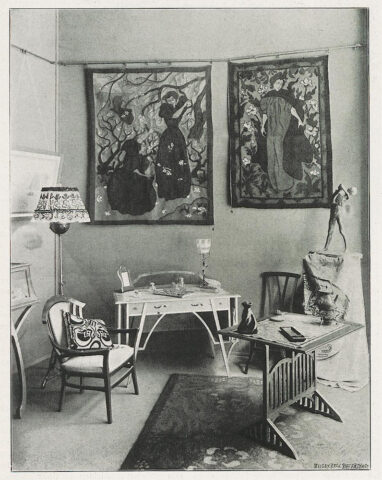

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

The establishment also offered a wide range of products: the article announcing its opening in September 1899 stated that “The galleries of the ‘Maison Moderne’ will contain a little bit of everything: furniture, upholstery fabrics, carpets, ceramics, glassware, lighting fixtures, embroidery, lace, jewelry, fans, toiletries, and fancy items—from brushes to cane knobs—in short, everything for the home and the person[3].” This prediction was clearly confirmed: La Maison Moderne offered everything needed to furnish an interior and all the accessories—except clothing—that a wealthy person in the early 20th century might need. The same article also mentions a selection of master painters whose works were offered for sale: Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Auguste Renoir, Maurice Denis, Théo Van Rysselberghe, Édouard Vuillard, and Pierre Bonnard. However, this article remains the only mention of the painting exhibition at La Maison Moderne. We do not know which paintings were exhibited there, and no other artists can be identified.

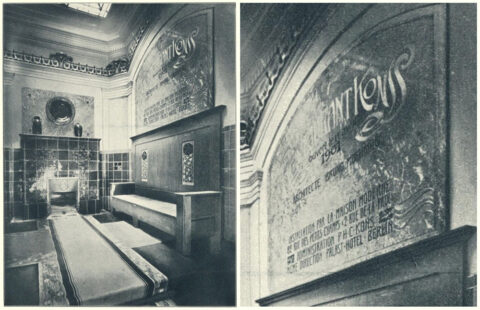

In addition to offering individual items for sale, the gallery also designed and furnished rooms, apartments, and other types of interiors. Most of these complete designs were carried out under the direction of Abel Landry, Pierre Selmershein, or Maurice Dufrène. No examples have survived other than old photographs, such as those of this fashion store, also designed by Van de Velde for the Palast Hotel on Potsdamer Platz in Berlin, managed by P. H. C. Kons.

Henri Van de Velde, interior design of a fashion store “filiale de Madame Henriette” in the Palast Hotel in Berlin, realized by La Maison Moderne with furniture designed by Abel Landry, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

The most important and best documented order was for the interior design of the German restaurant Konss[4], located in Paris on the corner of Rue Grammont and Boulevard des Italiens, on the first floor, also for P. H. C. Kons. The architect appointed by the owner to oversee the work was Bruno Möhring[5]. He decided on the overall layout of the place, and Kons renewed his trust in La Maison Moderne for the design and installation of the decorations. The work took place from January 15 to April 17, 1901. A real success, La Maison Moderne’s participation in the design was noted in the entrance hall of its establishment. A few months later, Meier-Graefe reported on it in L’Art Décoratif, under one of his pseudonyms: G. M. Jacques[6]. Reading this article, it is striking that, having signed it with a French-sounding pseudonym in his French magazine, Meier-Graefe adopts a point of view that could be that of a Parisian journalist, criticizing Möhring’s design by claiming that his “Latin instincts are closed to his Germanic conception.” “when it was in fact his own company that carried out the development. By sticking to what he imagined to be a ”Latin” mindset, he no doubt wanted to avoid any suspicion of a conflict of interest.

Bruno Möhring, landing on the staircase of the Konss restaurant, on the first floor of 30 rue de Grammont in Paris, 1901, executed by La Maison Moderne, ceramics by Laüger, Architektonische Monatshefte, VII. Jahrgang 1901, pl. 88, Leipzig/Vienna, Friedrich Wolfrum, 1901, online library of the University of Stuttgart.

Bruno Möhring, green dining room of the Konss restaurant, first floor of 30 rue de Grammont in Paris, 1901, executed by La Maison Moderne, panels by Georges de Feure, Architektonische Monatshefte, VII. Jahrgang 1901, pl. 87, Leipzig/Vienna, Friedrich Wolfrum, 1901, online library of the University of Stuttgart.

Bruno Möhring, lilac dining room of the Konss restaurant, on the first floor of 30 rue de Grammont in Paris, 1901, executed by La Maison Moderne, L’Art Décoratif, November 1901, article by G. M. Jacques (Julius Meier-Graefe). Online library of the University of Heidelberg.

La Maison Moderne’s operating model is very well thought out, reflecting its director’s careful consideration and innovative abilities. Aware of the behavior of French collectors, who treat art objects in the same way as paintings or sculptures, Meier-Graefe proposed an organization inspired by the Vereinigten Werkstätten für Kunst im Handwerk (United Workshops for Art and Craft) in Munich. While French decorative art remained primarily a commissioned art form, in which artists responded only to specific requests by creating unique models that could not be reproduced, Meier-Graefe proposed the opposite system: objects were no longer commissioned by individuals but were mass-produced by artists and craftsmen. However, production remained in the realm of craftsmanship and did not shift to industry. In the absence of administrative archives from the gallery, no precise figures can be given: the number of pieces produced for the same model must have been relatively small, but there were no unique works. Without even mentioning taste or style, it was first and foremost the way of thinking that the director of La Maison Moderne wanted to change.

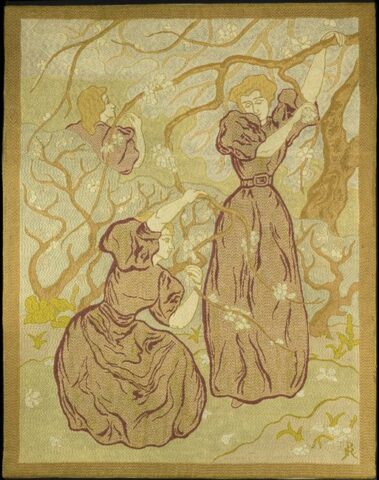

There were exceptions to this system. Tapestries by Paul-Élie Ranson, handmade by his wife France Ranson-Rousseau in single copies, were offered for sale at La Maison Moderne[7].

Paul-Élie Ranson, Printemps (Spring), wool tapestry on canvas executed by France Ranson-Rousseau, 1895, height 1.67 m, width 1.32 m, Musée d’Orsay, OAO 1788, rights reserved.

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris. On the wall, two tapestries by Paul-Élie Ranson: Printemps and Femme en rouge, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

Exhibition Femmes chez les nabis. De fil en aiguille (Women among the Nabis. From thread to needle) at the Pont-Aven Museum (June 22 to November 3, 2024), evoking the room in La Maison Moderne where Ranson’s tapestries were displayed. Photo by Bertrand Mothes.

However, these objects were made before the gallery opened and therefore do not fall under the manufacturing method developed by Meier-Graefe. The principle is simple: artists create designs and grant production rights to the gallery, which is responsible for executing them. The artist receives a portion of the sale price—defined by mutual agreement—for each object sold[8]. The possibility of producing multiple copies also allows Meier-Graefe to sell his objects at a “reasonable price,” in his own words. The “reasonable price” encourages purchases and provides the artist with a comfortable income. Here, “reasonable” should not be confused with “low.” While the prices of the objects sold at La Maison moderne did not reach those seen at Bing, they were nonetheless accessible to fairly well-off individuals, rather than workers or low-paid employees.

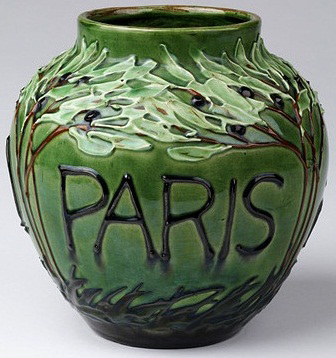

The gallery had its own workshops for the production of objects. The only one that can be confirmed with certainty is the leather workshop[9], but it is possible that there were also workshops for cabinetmaking, tapestry, brasswork, jewelry, and watchmaking. The fire arts, which were difficult to set up on a large scale in the heart of the Parisian capital, came from manufacturers associated with La Maison Moderne. The vase Exposition 1900 Paris, from Germany, is a good example. Manufactured by Tonwerke in Kandern, run by Max Laüger, it is not part of the factory’s usual production but was made exclusively for LMM, as evidenced by the gallery mark incised under its base alongside Laüger’s monogram and the factory mark.

Max Laüger, Tonwerke workshop, Vase Exhibition 1900 Paris, circa 1900, painted earthenware under glaze, produced by La Maison Moderne, height 0.212 m, London, Victoria & Albert Museum. All rights reserved.

Max Laüger, Tonwerke workshop, Vase Exhibition 1900 Paris, circa 1900, painted earthenware under glaze, height 0.212 m, Paris, Musée d’Orsay. All rights reserved.

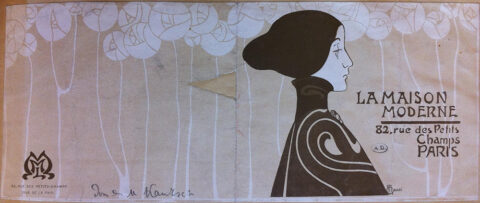

This approach to production and sales was complemented by a decisive choice of location for the gallery. 82 Rue des Petit-Champs is located just a few meters from Rue de la Paix, which remains one of the most prestigious shopping districts in Paris. In addition to being central, this location was frequented by a wealthy clientele receptive to artistic innovation. The street has since changed its name to Rue Danielle-Casanova. The former number 82 now corresponds to the current number 26, which is now occupied by a café.

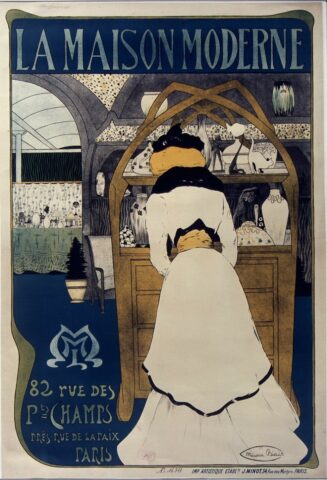

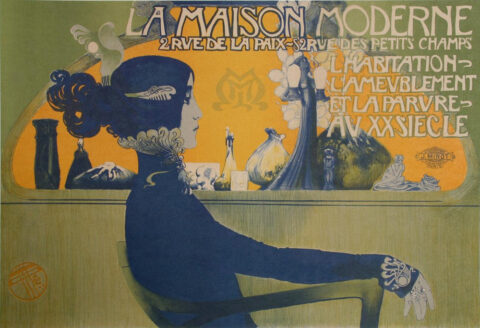

As the director of a commercial establishment, Meier-Graefe naturally used all the means available to him at the time to promote his gallery. Two posters were the cornerstone of his advertising campaign. The first was designed by Maurice Biais. It depicts an elegant lady looking at objects displayed in one of the shop windows designed by Van de Velde, faithfully reproduced.

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

Maurice Biais, J. Minot printing house, poster for La Maison Moderne, 1899–1900, color lithograph on paper, height 114 cm, width 0.785 cm, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

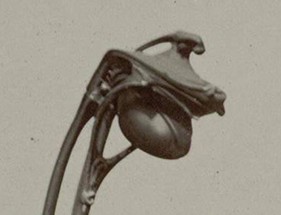

The objects depicted on the poster are all the more easily recognizable as Maurice Biais used photographs that would later be incorporated in the La Maison Moderne catalog. Among other items, the poster features a flamed enamel inkwell by Jakob Rapoport designed by Maurice Dufrène, small bronze sculptures by Georges Minne, a porcelain cat from the Danish manufacturer Bing & Grøndahl, and a lamp by Dufrène.

Maurice Dufrène, electric lamp, patinated bronze, no. 1580-1, height 0.55 m, Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (catalogue of La Maison Moderne), 1901, Lighting fixtures, p. 9. Private collection.

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg. To the left of the display case, Le Petit Blessé by Georges Minne.

Georges Minne, Le Petit Blessé, bronze, height 0.25 m, Nationalgalerie, Berlin. All rights reserved. This sculpture is reproduced in Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (catalogue of La Maison Moderne), 1901, La Sculpture, bronze no. 308-1, p. 21.

The second poster is the work of Manuel Orazi (fig. 5). With a composition and atmosphere completely different from that of Biais, it also features objects that were sold there. We can recognize an inkwell bearing a bronze figure by Alexandre Charpentier on a base designed by Dufrène and made of flamed stoneware by Adrien Dalpayrat, an armchair by Van de Velde, a bronze lamp by Gustave Gurschner, a vase by Dufrène and Dalpayrat, and a monkey figurine by Joseph Mendes da Costa. The distinctive feature of this poster is obviously the large, hieratic female figure that adorns it. This is in fact the famous dancer Cléo de Mérode, who lent her image to the gallery as its muse[10].

Manuel Orazi, J. Minot printing house, poster for La Maison Moderne, 1901, color lithograph on paper, height 0.83 m, width 1.175 m, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Gustav Gurschner, electric lamp, bronze, no. 718-1, height 0.48 m including lamps, Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (catalogue of La Maison Moderne), 1901, La Sculpture, p. 13. Private collection.

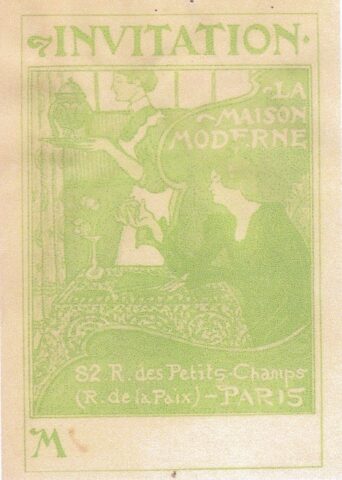

In addition to these posters, Meier-Graefe also published small leaflets designed to promote his gallery. The invitation card for the opening was designed by Georges Lemmen.

Georges Lemmen, invitation card to the inauguration of La Maison Moderne, 1899, color print on paper, height 0.19 m, width 0.13 m. Private collection.

The composition was also used as an advertisement in the pages of L’Art Décoratif. The two women depicted are not anonymous, as they are actually Mrs. Meier-Graefe and Jenny, a young servant.

The second print was created by Manuel Orazi, who drew inspiration from his own poster for the design.

Manuel Orazi, brochure for La Maison Moderne, circa 1903, lithograph on paper, height 0.117 m, width 0.277 m, Paris, Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs.

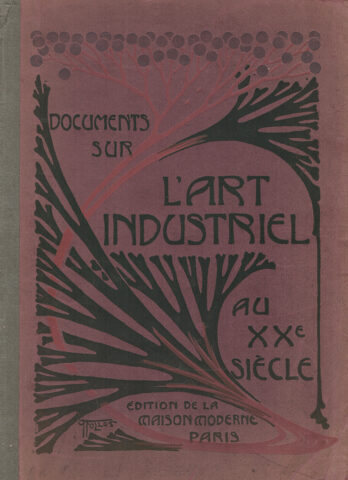

Meier-Graefe also printed discount coupons from the same poster, either for his best customers or to attract new ones. One of his most important advertising tools remained the book Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (Documents on Industrial Art in the Twentieth Century), published in 1901.

Paul Follot, Cover of Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, Paris, Édition de La Maison Moderne, 1901, height 0.30 m, width 0.208 m. Private collection.

Presented as a collection of the most beautiful works of art of the period, it is in fact the gallery’s commercial catalog, containing many references to objects from La Maison Moderne.

Félix Aubert, Maison Georges Robert, Iris fan no. 54-V and its box, c. 1900, polychrome silk lace, horn, emerald, pearl, height 0.28 m, diameter 0.48 m, Caen, Musée de Normandie. All rights reserved. This fan is reproduced in Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, 1901, La Dentelle, p. 4.

In addition to these independent advertisements, Meier-Graefe filled the magazines he edited with constant references to his gallery and collaborating artists. He also participated in events such as the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts in Turin in 1902, for which he published a postcard featuring real objects from his shop.

Maurice Biais, Société Éditrice Cartoline, Main hall of “La Maison Moderne” at the Turin Exhibition, 1902, vintage postcard, Miami, The Wolfsonian-Florida International University. All rights reserved.

However, despite all its innovative ideas and pioneering role at the beginning of the 20th century, the gallery was a failure. Its director sold it in 1904 to Delrue et Cie, who took charge of liquidating the stock[12]. The climate of xenophobia in Paris was detrimental to both Meier-Graefe and Bing, as French collectors resented a German coming to lecture them on what their taste should be[13]. Furthermore, although its structure was ingenious, production costs remained too high for the gallery to remain viable.

Abel Landry, armchair n° 43, produced by La Maison Moderne, mahogany, modern upholstery, height 1.04 m, width 0.75 m, depth 0.90 m, Zéhil gallery, Monaco. Photo: Zéhil gallery. This armchair is reproduced in Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, 1901, Furniture and decoration, p. 16.

This gallery, led by an innovative director with impeccable taste, never managed to find its audience, but remains the only real attempt in 1900 to create an alliance between art, industry, and commerce.

Bertrand Mothes

Translation: Alan Bryden

Notes

[1] Roger CARDON, Georges Lemmen (1865-1916), Antwerp, Petraco-Pandora, 1990, p. 449.

[2] Cat. Exp Georges Lemmen 1865-1916, Brussels, Crédit Communal, Ghent, Snoeck-Ducaju & Zoon, Antwerp, Pandora, 1997, p. 58.

[3] R. [pseudonym Julius MEIER-GRAEFE], “Chronique de l’art décoratif, La ‘Maison Moderne’,” L’Art Décoratif, September 1899, no. 12, p. 277.

[4] It is likely that the doubling of the final “s” in the restaurant owner’s name was intended to make it sound German and avoid confusion with a French word that was a little too similar.

[5] In 1900, Möhring had already built the Restaurant allemand at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, which was a great success.

[6] G. M. JACQUES, “Un restaurant allemand à Paris,” L’Art décoratif, November 1901, no. 38, pp. 54-60.

[7] Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle. Photographic reproductions of the main works of the contributors to La Maison Moderne. Commented by R. [Raoul] AUBRY, H. [Henri] FRANTZ, G.-M. JACQUES [pseudonym Julius MEIER-GRAEFE], G. [Gustave] KAHN, J. [Julius] MEIER-GRAEFE, Gabriel MOUREY, Y. [Yvanhoé] RAMBOSSON, E. [Émile] SEDEYN, Gustave SOULIER, G. [Georges] BANS, with nine additional illustrations by Félix VALLOTTON Les Métiers d’Art. Paris, Édition de La Maison Moderne, 1901, L’Ameublement, p. 36.

[8] R., op. cit. in note 3, p. 277.

[9] Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, op. cit. in note 7, La Maroquinerie, p. II.

[10] Alexandre Charpentier (1856-1909).Naturalisme et Art Nouveau, exhibition catalog, Paris, Musée d’Orsay, N. Chaudun, 2007, p. 126.

[11] Roger CARDON, Georges Lemmen (1865-1916), Antwerp, Petraco-Pandora, 1990, p. 449.

[12] Advertisement for La Maison Moderne, Delrue et Cie, Fermes et Châteaux, November 1905, no. 3, p. IX.

[13] Nancy J. TROY, Modernism and the Decorative Arts in France: Art Nouveau to Le Corbusier, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1991, p. 47.

List of artists mentioned in the Documents sur l’Art Industriel au XXème siècle (Documents on Industrial Art in the Twentieth Century)

Félix AUBERT

Henri BANS

Gyula BETLEN

Maurice BIAIS

Alexandre BIGOT

[manufacture] BING & GROENDAHLSofie BURGER HARTMANN

Alexandre CHARPENTIER

Cristallerie de Pantin

Jens DAHL-JENSEN

Pierre Adrien DALPAYRAT

Eugène DELATRE

Maurice DUFRÈNE

Paul FOLLOT

Édouard FORTINY

Maurin GAUTHIER

Gustave GURSCHNER

Bernhard HOETGER

Henry JOLLY

Emil KIEMLEN

G. KISS

Abel LANDRY

Georges LEMMEN

Hans Stoltenberg LERCHE

Clément MÈRE

Charles MILÈS

Georges MINNE

Koloman MOSER

Gabriel OLIVIER

Manuel ORAZI

Blanche ORY-ROBIN

Paul-Élie RANSON

Jakab RAPOPORT

Auguste RODIN

SAINT-YVES SCHLESINGER

Elisabeth SCHMIDT-PECHT

Tony SELMERSHEIM

Louis Comfort TIFFANY

Henry VAN DE VELDE

Heinrich VOGLER

Félix VOULOT

François WALDRAFF

To quote this article:

Bertrand MOTHES, “La Maison Moderne de Julius Meier-Graefe” in Catherine Méneux, Emmanuel Pernoud, and Pierre Wat (eds.), Proceedings of the Study Day Actualité de la recherche en XIXesiècle, Master 1, Years 2012 and 2013, Paris, HiCSA website, published online in January 2014.

Jules Lavirotte: a new version of the book is published by the Cercle Guimard — an exhibition is dedicated to him in Évian — the building of the Châtelet mineral water company

9 May 2025

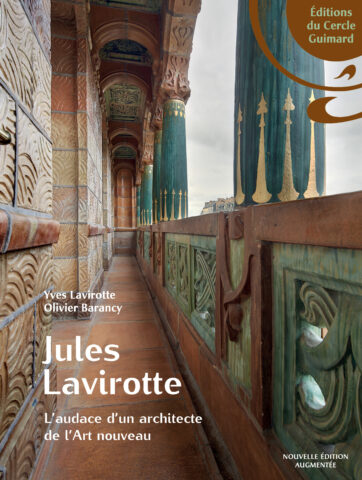

In 2018, the Jules Lavirotte Association published its first book dedicated to the life and work of an architect whose fame is paradoxical: although his name and some of his works are well known to the public, his life and career were virtually unknown even to specialists. This year, authors Yves Lavirotte and Olivier Barancy chose the Cercle Guimard for the publication of a revised and expanded edition of the book. Although the first version—now out of print—was remarkable, this new edition surpasses it. In 192 pages with numerous illustrations, the authors complete the architect’s career with previously unpublished information and new works. The book is available since the end of May 2025 at a price of €35. Its publication will be followed by a book signing and guided tours dedicated to Lavirotte’s work, events which we will come back to shortly.

To mark the launch of this new edition, the authors have seized the opportunity of an exhibition dedicated to the architect, organized with their assistance by the city of Évian at the Villa du Châtelet, from June 1 to September 30, 2025.

Olivier Barancy tells us the story of the thermal baths built in Évian by Lavirotte, of which the Villa du Châtelet is one of the remaining buildings.

General view of the refreshment bar, lake side, old photograph. Private collection

Following the acquisition on April 4, 1906, by Arthur Sérasset and Émile Lavirotte of land built on the shores of Lake Geneva in Évian-les-Bains, Jules Lavirotte was approached by his brothers to build a spa on the newly acquired land. The architect immediately set to work and construction began quickly.

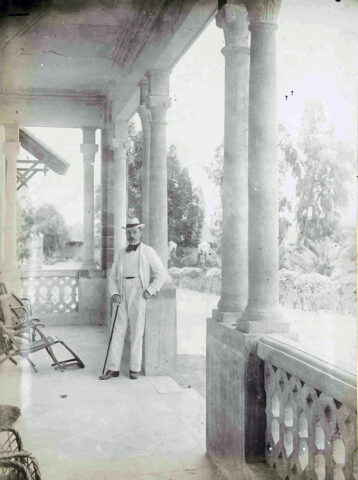

Jules Lavirotte in a gallery of the refreshment bar, old photographic print. Private collection.

The project is significant: on a sloping plot of approximately 15,000 square meters, with a length of over 100 meters along a busy road that runs alongside the lake, a new building, the “buvette,” is to be constructed at 29 Quai Paul-Léger. This will incorporate a small, recently built (1898) neo-Renaissance villa with a charming layout. A patio designed by the architect will connect the new building to the existing part, which will house the offices. The refreshment bar included all the facilities necessary to welcome spa guests, as well as commercial services linked to the offices. In addition, two existing villas, including the one known as the Châtelet, which gave its name to the spa complex, were converted to accommodate spa guests, along with the service building and the gardener’s house at the top of the park, which housed the staff. The refreshment bar, in late Art Nouveau style, is spread over three levels. The ground floor houses the commercial bottling area, including a covered unloading bay and services. The first floor comprises, on the lake side, a large gallery with paired columns, flanked by a reading room and a large lounge; and on the south side, opposite the lake, a “luxuriously appointed refreshment room” connected to a “lunchroom.” The whole building is covered by reinforced concrete terraces accessed by a staircase sheltered in a graceful bell tower on the west side of the facade. To the east and at the opposite corner, another bell tower, with a slender silhouette, rises to a height of 16 meters. These two structures make the building visible from afar, in accordance with an architectural technique commonly used in the design of public buildings. The interior design is luxurious: a large stained-glass window[1] at the end of the south gallery depicts a landscape of snow-capped mountains with a stream flowing down from them; the walls are decorated with antique-style frescoes depicting fountains and garlands; and from the ceiling hang chandeliers with golden branches, decorated with three-tone leaves and clusters of Murano glass[2]; Finally, mosaics cover the floor. In the park, a stream winds its way between rockeries and flows through a rustic kiosk, where water from a second spring also flows, behind the “châtelet.” The establishment was inaugurated at the end of 1910.

Françoise Breuillaud-Sottas, a specialist in thermalism in Évian, highlighted the originality of the project: “Only the Châtelet spring is associated with a genuine hydrotherapy establishment.”

A gallery in the refreshment bar, overlooking the park, featuring old photographic prints. Private collection.

At the same time, Arthur Sérasset, administrator of the Société des Sources du Chatelet and partner of Émile Lavirotte, gave Jules Lavirotte “full powers” to find and fit out shops in Paris to sell the bottles of mineral water. He opened at least two, at 36 Boulevard des Italiens and 56 Boulevard de Bercy. The finishings of the refreshment bar appear to have been carefully executed, as some of the contractors were the same as those who worked on the mansion on Avenue de Messine in Paris. Finally, in 1909, the architect designed the Office des Baigneurs (bathers’ office) at 4 Avenue du Port in Évian. It was a modest premises for a real estate agency, which also owned the newspaper Évian Mondain.

However, the additional commission for the construction of the grand hotel overlooking the park was difficult to obtain, as the shareholders’ meeting criticized Lavirotte for his lack of follow-up on the first building and for exceeding the budget. They demanded the presence of an assistant architect on site: this was Étienne Curny (1861-1945), who was active in Lyon and the surrounding region. The main features of the project drawn up in 1907 were more traditional than the refreshment bar, although the large terrace overlooking the lake, the bold canopy over the south entrance, and the floral friezes surrounding the building under the attic were noteworthy. However, at the request of the clients, the plans were significantly modified to reduce costs and increase the number of rooms. The north façade in particular, with its balconies, two avant-corps, and an asymmetrical slate roof, bears little resemblance to the initial sketch. Lavirotte ultimately withdrew from the project.

Auguste Labouret, large stained glass window in the refreshment bar, on the park side.

Photo by Christophe Lavirotte.

In 1925, a scandal erupted around the water from the Évian-Châtelet springs: its managers, including its president, Mr. Bocheux, were sentenced to several months in prison for selling mineral water that did not meet health standards. The following year, the Hôtel du Châtelet was renamed the Hôtel du Parc. Then, in 1938, the refreshment bar was demolished[3] to make way for a road connecting the quay to the hotel where, on March 18, 1962, the Évian Accords were signed, ending the Algerian War.

Olivier Barancy

Notes

[1] Designed by Auguste Labouret (1871-1964), a prolific master glassmaker based in Paris.

[2] Jules Lavirotte went to Venice himself to choose them.

[3] Some elements were preserved and displayed in the park.

Translation: Alan Bryden

A Guimard’s metro signaling glass (“verrine”) for our museum project

( Note: in this article, the term “signaling glass” is used to translate the French “verrine”, meaning the protective cover of the lamp in a Guimard Metro candelabra)

If you could not attend our last Annual General Meeting, you may not have been able to see – or touch – our latest purchase: a Guimard metro candelabra signaling glass produced by the Cristallerie de Pantin. In a recent article, we corrected our earlier opinion [1] by admitting, with supporting evidence, that these signaling glasses were originally white, and that the change to an orange-red color took place around 1907, four years after Guimard’s collaboration with CMP (Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris) came to an end.

We would point out, however, that it was likely that red signaling glasses existed at an early date, since the detail of a black-and-white photograph of the uncovered surround of Rome station, taken in 1903 shortly after its installation, is more compatible with a red color than a white one.

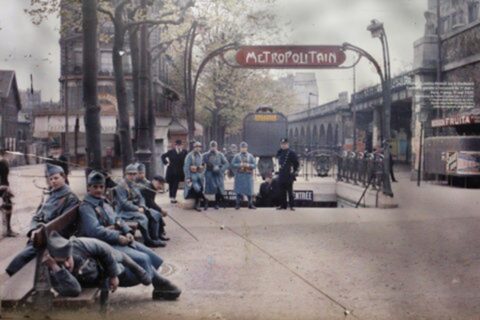

Rome station open surround (detail), installed in 1902. Photo Charles Maindron (1861-1940) CMP photographer. Silver chloride gelatin print developed on June 5, 1903. École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, Direction de la documentation, des archives et du patrimoine.

On the contrary, white glass was used for at least one of the last surviving shield surrounds, installed at Porte d’Auteuil station in 1913.

Surround of the Porte d’Auteuil station. Photo Heinrich Stürzl, based on an autochrome plate by Frédéric Gadmer, taken May 1, 1920. Musée départemental Albert-Kahn collection (inv. A 21 126). Source Wikimedia Commons.

At least one of these white signaling glasses still exists in a private collection, as we know it from a detailed photograph [2] taken in 1967.

White glass used as a chandelier. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulme (detail). Cercle Guimard archives and documentation center.

A total of 103 open shield surrounds were installed between 1900 and 1913. One of these had already been dismantled in 1908, leaving 102 on the eve of the First World War. At a rate of two signaling glasses per surround, there were therefore 204 signaling glasses on the network at that time. Subsequently, the number of signaling glasses fell considerably because of the many dismantling operations that took place until 1978, when all the Guimard entrances were finally classified. At that date, there were still 60 uncovered entourages with shields. Logically, in the interest of optimal material management, the removed signaling glasses of the surrounds should have been stored, but we don’t know what happened to them.

As for the remaining signaling glasses on the network, whether red or white, they were all replaced by synthetic equivalents, probably in the 70s [3]. The motivation for this exchange can easily be guessed. It wasn’t a question of protection against vandalism, which was still in its infancy [4], but simply a maintenance constraint. These rather heavy glass vessels had to be handled when a lamp had to be replaced. This rather delicate handling, repeated dozens of times, led to numerous accidents on the necks of the signaling glasses and sometimes to their destruction. What’s more, the Pantin crystal glassworks had probably stopped producing new pieces a long time ago, so RATP was no longer able to renew them. The RATP therefore decided to replace them with copies made of synthetic material, which were lighter and less fragile, but far less beautiful. In the process, it dismantled at least a hundred signaling glasses, which should also have been put into storage.

Plastic signaling lamp cover Coll. Hector Guimard diffusion. Photo F. D.

By 2000, however, R.A.T.P. no longer owned a single one. What had happened? Unfortunately, the certainty that these signaling glasses would no longer be used on the network meant that this stock was probably managed in a less than rigorous manner. The lack of interest in, or even disdain for, the Art Nouveau style for many years meant that they had neither the artistic nor the financial value that would have encouraged R.A.T.P.’s management to preserve them. At the same time, however, private collections were being made, either out of aesthetic interest and without the feeling of committing a criminal act, or out of greed, since as early as the 1980s, Guimard metro pieces were being smuggled out of France, notably to make bronze copies for sale in the United States [5]. Authentic signaling glasses were found on at least one bronze subway surround in Houston.

Fortunately, before it no longer owned any, R.A.T.P. had, this time officially, loaned or donated signaling glasses along with complete surrounds, notably to the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1958, the Staatliches Museum für Angewandte Kunst in Munich in 1960, the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris in 1961 (transferred to the Musée d’Orsay) and then to the Montreal metro company in 1966. During the restoration of the latter, the STP subway company also disassembled its signaling glasses, giving one back to the RATP in 2003 [6].

On September 4, 2003, Mrs Anne-Marie Idrac, President of RATP, receives from Mr Claude Dauphin, Chairman of the STM’s Board of Directors, one of the two vintage signaling glasses from the surround shipped to Montreal in 1966. Photo coll. STM

We concluded our previous article on the color of signaling glasses by prophesying that such glasses would inevitably reappear as the generations of their private owners changed. And this is precisely what happened: in October 2024, a few months after the publication of our article on glassware colors, one of our faithful correspondents — half-serious, half-amused — alerted us to the publication on a well-known free classified ads site of a proposal to sell the end of a subway candelabra with its glassware.

Photo provided by the seller of the Guimard metro candelabra end for a sale ad posted on the Le Bon Coin website.

We immediately got in touch with the advertiser, who confirmed that it was cast iron (not bronze) and that the signaling glass was indeed made of glass. Given the rarity and interest of such an object, we quickly agreed on a price with the seller, and a family friend immediately dismantled it and put it in a safe place until it could be shipped to the Paris region.

End of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

As we had expected, the discussion with the vendor revealed that its owner (who had recently passed away) had held a fairly senior position in the RATP maintenance hierarchy, and that upon his retirement in the mid-80s, he had been given an entire metro lamp post. However, the size and weight of such an object made it very difficult to handle and use, so the happy new owner decided to saw off the end for outdoor use on his holiday home in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques region, where he was originally from. The remaining part rusted away for a few years outdoors in the Paris region, before being sold for its weight in metal.

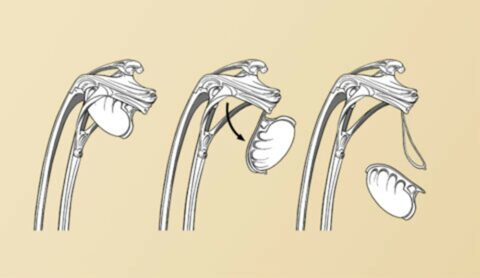

Once the end of the candelabra had been recovered, we separated it from its sheet metal support. The signaling glasses had previously been removed from its housing. To do this, it was necessary to remove the cross-pin (held in place by a chain) which held the collar in place at the back.

End of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

The collar, held at the front by a hinge, can then be tilted to release the signaling glasses.

End of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

Disassemble the signaling glass by unlocking the collar. Drawing F. D.

The post of the candelabra has been cut away, revealing the hole through which the lamp’s power supply passes.

End of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

The signaling glass was simply cleaned with soapy water, pending a more thorough cleaning. As we feared, its neck shows a lot of missing parts due to handling during lamp changes.

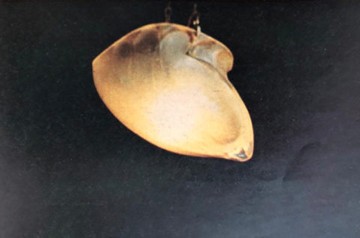

Signaling glass of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

Weighing 6.5 kg, it measures 40 cm in overall length and 24 cm in height. Its maximum width is 26 cm, less than it should be (28 cm) due to the missing collar. The opening measures 26 cm by 20 cm.

Signaling glass of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

Nevertheless, most of the signaling glass is in excellent condition and, with the difference that its neck is more uneven, our glass is identical to that of the RATP: same clean lines, satin-finish surface and color that varies according to the lighting and thickness of the glass, from dark red to light orange.

Signaling glass of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

A piece of old glass sent to us by the seller shows that the glass is colored in the mass and not plated on the surface.

Edge of a shard from the neck of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

The fact that the signaling glasses were made in a crystal factory and not in a glass factory raised a question: was the material crystal or indeed glass? The shard above gave us an easy answer. Its weight is 8 g and its volume (obtained by dipping it into a graduated tube and measuring the rise in water level) is 3 ml, giving a density of 8/3 = 2.6, that of glass (that of crystal being 3.85).

Measuring the volume of the shard of the signaling glass in a graduated tube. Photo M.-C. C.

Let’s recall the manufacturing process for this signaling glass as carried out by the Cristallerie de Pantin. A bivalve mold is used, articulated around its sagittal axis and based on a plaster model supplied by Guimard. To obtain the correct “point”, the glassmaker places a pellet of molten glass at the bottom of the mold. The gob of glass (the volume of glass picked from the jar at the end of the cane) is shaped by balancing and shaping, then introduced into the mold. A layer of about 8 mm of glass is then pressed onto the inner surface of the mold by air blown into the cane. The mold is then opened and the glass vessel cut with scissors to expose the wide opening. The edges are bent with pliers and probably shaped by applying another mold around the opening. After cooling, any imperfections and seams caused by the mold joints are carefully ground away. Finally, the outer surface of the signaling glass is acid-etched.

Signaling glass of a Guimard metro candelabra. Coll. Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

The aspect of this signaling glass has not failed to elicit comparisons with well-known shapes: teardrop, fruit, frog’s eye. One of the most disparaging comparisons, “half-sucked candy” [7], is not the most inaccurate. It’s not impossible that Guimard’s illustrative intent was to evoke a flame, as if spat from the end of candelabras. But now that we know that the first signaling glasses were white, this hypothesis seems less credible. It also seems possible that Guimard wanted to capture the look and workings of molten matter, with the signaling glass appearing to be both blown and then pinched at the end and stretched (this action being reflected in the wide striations around the neck). The idea of evoking a downward flow of viscous matter is also admissible, as Guimard was able to illustrate it, notably on the low-end posts of the secondary surrounds. As is often the case in his art of semi-abstract drawing and modeling, many interpretations are relevant, and everyone is free to formulate their own.

The Cercle Guimard was delighted to acquire this candelabra end piece and its signaling glass. It will of course be one of the centerpieces of the section devoted to the Paris metro in our museum project at the Hôtel Mezzara.

Frédéric Descouturelle

Notes

[1] Descouturelle, Mignard, Rodriguez, Le Métropolitain de Guimard, éditions Somogy, 2003; Descouturelle, Mignard, Rodriguez, Guimard L’Art nouveau du métro, éditions La Vie du Rail, 2012. [2] As announced in our previous article, we will one day devote a special article to the astonishing batch of photographs of which it is a part. [3] We give this very approximate date as a matter of conjecture. When writing the books on Guimard’s metro, we were unable to discover the exact date of this replacement. [4] Unfortunately, at present, the reinstallation of signaling glasses, which are easy and very expensive targets, seems to us to be completely unrealistic. [5] See our articles on this subject: “The epidemic of fake bronze subway surrounds in the United States”: part one; the epidemic…part two; The epidemic…part three. [6] The other signaling glass was entrusted to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. [7] Quoted without reference by R.-H. Guerrand in Mémoires du métro, 1961. The article or book from which this quotation is taken has not yet been found.

Translation: Alan Bryden

A rare crystal vase by Guimard

22 May, 2025

Tracked for years, this exceptional vase has recently been added to the collections of our partner for the Guimard Museum project. Lengthy negotiations led to the acquisition of this rare object, the first of its kind to be identified and described. Unlike other areas of decorative arts where Guimard was prolific, he produced very little glassware.

Guimard vase from the Cristallerie de Pantin, height: 40.2 cm, outer diameter at the opening: 5.2 mm, outer diameter at the base: 12.7 cm, weight: 1.437 kg. Private collection. Photo F. D.

The overall shape is fairly common for Art Nouveau glassware, resembling a “bottle vase” that can be divided into three parts: a very flat base highlighted by a protrusion, a slightly conical body, and a narrowing at the top before the opening curves outward. This shape, with its swirling ribs, seems to be unique to Guimard, who did not attempt to reproduce the silhouettes of his designs for bronze or ceramics. But as we shall see later, are we sure that Guimard is the creator of this shape?

This vase remained in the seller’s family for a long time, but it has not been possible to ascertain the original conditions of purchase. It is in good condition, despite a few scratches and a slight limescale deposit showing that it was once used as a flower vase.

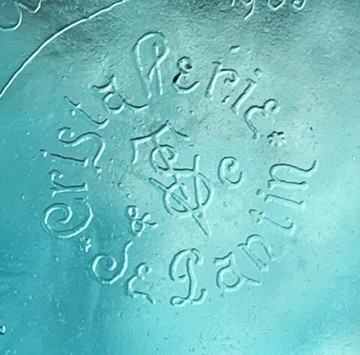

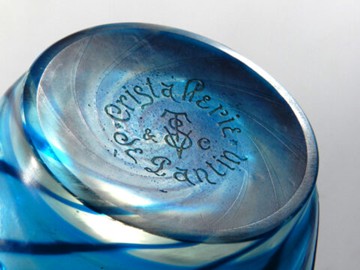

It was produced at the Cristallerie de Pantin[1], as indicated by the signature engraved on its base, around the “STV” logo, which stands for the initials of the crystal factory’s full name: Stumpf, Touvier, Viollet & Cie.

Signature of Cristallerie de Pantin on the base of the vase. Private collection. Photo Justine Posalski.

Measuring 40.2 cm high and weighing 1.437 kg, it has a volume of 0.480 liters. These last two figures can be used to calculate its density: 2.99, very close to that of classic lead crystal (3.1).

Calculation of the volume of the Guimard vase from the Cristallerie de Pantin. Private collection. Photo Fabien Choné.

The question of the exact nature of the material arose, even though the vase came from a crystal factory, because we established that the glass shades of the candelabra in the subway entrances produced by the same factory from 1901 onwards were made of glass without any added lead. The Cercle Guimard recently purchased one copy.

Glass shade of a Guimard metro candelabra. Collection of Le Cercle Guimard. Photo F. D.

The base of the vase also bears Guimard’s handwritten, curved signature. It is characterized by the continuity of the design in a single line joining the first and last names and ending with a long initial that returns emphasizing them. It should be noted that the execution at the tip is slightly more hesitant than that of the crystal factory logo, for which the worker assigned to this repetitive task had a stencil.

Guimard’s signature on the base of a vase from the Cristallerie de Pantin. Photo Justine Posalski

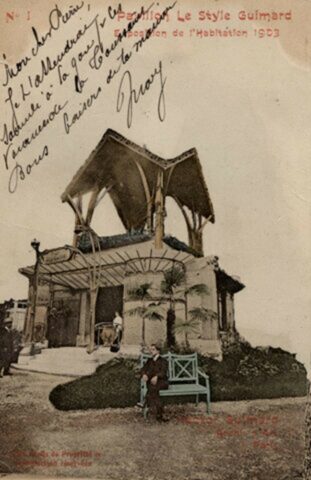

The “Le Style Guimard” pavilion at the Housing Exhibition at the Grand Palais in 1903. Vintage postcard no. 1 from the Le Style Guimard series. Private collection.

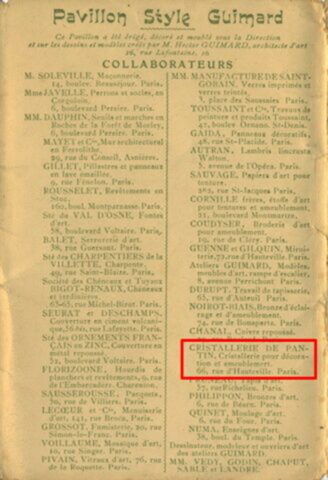

In the list of contributors included in the brochure accompanying the series of postcards, mention is made of the Cristallerie de Pantin, located at 66 rue d’Hauteville, where their Paris store was located.

Partial view of the packaging insert for the Le Style Guimard series of postcards. Private collection.

The crystal factory was included in this list of collaborators, certainly for the glass shades of the metro entrance that framed the entrance to Guimard’s pavilion, and possibly also for another product on display: probably vases, as suggested by the description that Guimard associated with the supplier’s name: “crystalware for decoration and furnishings.” Unfortunately, the views of the interior of the pavilion that we have do not show these vases. Moreover, there is no indication that the crystalware presented in the pavilion at that time was already the result of a collaboration between the architect and the Cristallerie de Pantin. Guimard may simply have chosen products from the glassworks’ catalog to decorate the furniture on display. The following year, however, we became certain that this collaboration had indeed taken place. In the booklet that Guimard published for the 1904 Salon d’Automne, he detailed his shipment by category. Number 4 of the “Objets d’art Style Guimard” is described as follows: “Guimard-style vase in aquamarine crystal. Price: 65 francs.“

The name ”aquamarine” was not invented by Guimard, who instead incorporated it into a production line of the Cristallerie de Pantin that had started a few years earlier. It refers, of course, to the name of the gemstone, a variety of beryl with a light blue color reminiscent of the sea. These bluish shades, which are difficult to achieve, were sought after empirically by various French crystal manufacturers. Émile Gallé in Nancy, for example, used cobalt monoxide to obtain a very light blue color called “moonlight,” which was unveiled at the 1878 World’s Fair. At the Cristallerie de Pantin, to obtain a slightly opaque glass with intermediate turquoise iridescence, the yellow of uranium dioxide and the green of a chromium oxide were mixed with cobalt blue.

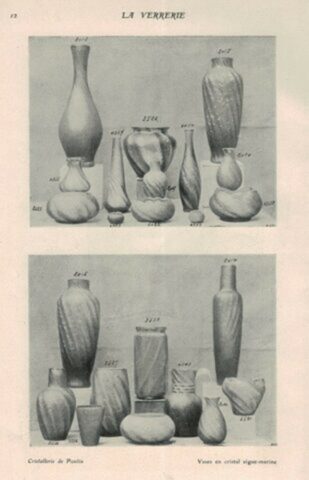

The first mention of the production of “aquamarine” crystals by the Cristallerie de Pantin that we know of appeared on a page of the Maison Moderne catalog[2] published in 1901.

Documents on « l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle » (catalogue of La Maison Moderne), Paris, Edition de La Maison Moderne, 1901, p. 12, “Crisallerie de Pantin/Vases en cristal aigue-marine.” Private collection.

In the two photographs on this page, twenty-two vases of different shapes and a colors that can only be described as bluish all feature swirling ribs, often regularly punctuated with reliefs like the surfaces of shells, another way of recalling the marine inspiration of the series. The creator or creators of these modern shapes are not mentioned, suggesting that they were probably employees of the crystal factory[3].

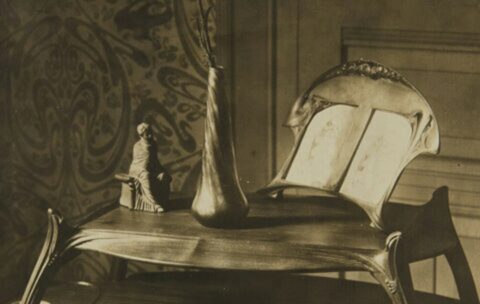

Guimard’s crystal vase was not completely unknown to us, as documents from the Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard donation kept at the Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs identify at least two examples decorating a piece of furniture probably presented at the Salon d’Automne.

Coll. Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs, donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Within the same collection of documents, another twisted vase model, with a more pear-shaped base and a more tapered neck, is very similar to No. 4357 on the page of the Maison Moderne catalog (see above). However, Guimard’s involvement in this piece has not been confirmed.

Coll. Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs, donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Another example of a vase that could have come from the Cristallerie de Pantin is the translucent crystal model displayed in the showcase of the grand salon at the Hôtel Guimard, which features the same type of twists.

Detail of the window display in the grand salon of the Guimard Hotel.

Private collection.

It should be noted that none of these vases feature any added floral decoration imitating the style of Gallé and Daum glassware from Nancy. This may have been a specific request from Maison Moderne, which wanted a more understated design in keeping with the Belgian style championed by Van de Velde. Outside of Maison Moderne, Cristallerie de Pantin produced numerous models of “aquamarine” vases with floral decoration, which occasionally appear on the art market.

Aquamarine vase with floral decoration engraved with acid from Cristallerie de Pantin, online gallery les_styles_modernes, sold on eBay Netherlands, May 2025, height 24.8 cm, diameter 10.3 cm, weight 796 g. Photo les_styles_modernes, rights reserved.

Aquamarine vase with floral decoration engraved with acid from Cristallerie de Pantin, online gallery les_styles_modernes, sold on eBay Netherlands, May 2025, height 24.8 cm, diameter 10.3 cm, weight 796 g. Photo les_styles_modernes, rights reserved.

Like these vases, Guimard’s vase also features an acid-etched decoration, but one that is unique to him and reflects his efforts to renew his semi-abstract style, gradually moving away from the harmonious arrangements of curved or whimsical lines that characterized his work around 1900.

Detail of the decoration on the Guimard vase from the Cristallerie de Pantin. Private collection. Photo F. D.

Once again, it is not easy to describe or interpret this design, which leaves the observer’s imagination free to find its own references. While a plant-inspired motif seems to be ever-present, with highly stylized stems and flowers repeated ten times around the circumference, a motif inspired by the treble clef is not impossible.

Detail of the decoration on the Guimard vase from the Cristallerie de Pantin. Private collection. Photo F. D.

Some of the undated watercolor drawings of frieze designs donated by his widow Adeline Oppenheim to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs show some stylistic similarities.

Guimard, detail of a design for a frieze, watercolor on paper. Collection of the Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs, donation of Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Other elements of the decoration, such as the blue lines and the yellow coloring at the top, allow us to speculate on how the vase was made. As with any glassmaking process, the glassmaker would have taken a parison from the furnace using his hollow rod and given it an initial shape by blowing and swaying it. He then rolls the parison on the “marble” (a polished cast iron table) to add calcined bone powder and arsenates, which have been placed there beforehand and which will give the glass a satin appearance over the entire height of the vessel and a yellow coloration in its upper quarter. In addition, twisted blue threads, visible at the top and bottom of the vase, were prepared in advance, laid down and then covered with a new layer of glass, which was returned to the furnace. This is therefore an intercalated decoration and not the usual Venetian thread technique, where the threads are applied to the surface.

Guimard vase neck from the Cristallerie de Pantin with blue intercalated fillets. Private collection. Photo F. D.

Base of the Guimard vase from the Cristallerie de Pantin with blue intercalated strips. Private collection. Photo F. D.

With the glass vessel still at the end of the rod (on the side of the future opening), the base is roughly shaped by gravity and tapping against the marble. It is then placed in the clamshell mold and blown so that it sticks to the walls. This is when most of the swirling relief is created. Once the mold is opened, the vessel is picked up under the base using a small amount of molten glass at the end of an iron rod (the pontil). On the opposite side, the neck is twisted (as evidenced by the arrangement of the air bubbles that follow this movement) before being detached from the rod by cutting it with scissors and shaping it with pliers.

Guimard vase neck from the Cristallerie de Pantin. Private collection. Photo Justine Posalski.

After cooling slightly to ensure stability, the vessel is coated with a thin layer of a more intense blue glass, which the glassmaker takes from a second furnace. The vase is then detached from the pontil, which leaves a scar under the base. After gradual cooling, the blue glass coating on the surface is treated with hydrofluoric acid. To reveal the decoration that will be preserved in blue, the surface is first protected with a varnish (at that time, Judea bitumen), while the unprotected surfaces are removed with acid until the underlying glass appears. Under the base, the trace of the pontil is removed by grinding and polishing so that the crystal manufacturer’s logo and Guimard’s signature can be engraved, as we saw above. However, around the opening, the remaining surface irregularities show that the glass has not been reworked by grinding.

Guimard vase neck from the Cristallerie de Pantin. Private collection. Photo F. D.

The main reason why this vase came to the attention of Guimard specialists so late was its rarity. Its imperfect execution, particularly evident in its fairly substantial bubbling, suggests that it was part of a very small series. The other reason is that its attribution to Guimard is not obvious at first glance. It is even likely that, in the absence of a signature[4] and despite its abstract naturalistic decoration, this vase would not have aroused the same interest on our part, nor would it have prompted the research that followed to find the rare clues that enabled us to locate it within Guimard’s works. At the same time as he wanted to simplify the Guimard style by reducing it to a simple decoration on an object that could ultimately be adapted to all styles of interior design, it is quite likely that Guimard also chose a vase shape that already existed at the Cristallerie de Pantin — a shape that was not necessarily already on the market — and “Guimardized” it, thereby replicating the same approach he took with products from certain other manufacturers, as we have demonstrated for the stoneware vases produced by Gilardoni & Brault[5].

Frédéric Descouturelle and Olivier Pons,

with the assistance of Justine Posalski and Georges Barbier-Ludwig.

Notes

[1] The crystal factory was founded in 1847 at 84 Rue de Paris in Pantin and taken over in 1859 by E. Monot, a former worker at the Lyon crystal factory. It quickly prospered, becoming the fifth largest crystal factory in France and then, after the 1870 war (and the transfer of the Saint-Louis crystal factory to German territory), the third largest (after Baccarat and Clichy). The crystal factory industrially manufactured a complete range of products, which it displayed in its Paris store on Rue de Paradis. Its warehouse was also in Paris, at 66 Rue d’Hauteville. The company name changed several times: “Monot et Cie,” then “Monot Père et Fils et Stumpf,” and finally “Stumpf, Touvier, Viollet & Cie” after Monot withdrew in 1889. It was absorbed in 1919 by the Legras glassworks (Saint-Denis and Pantin Quatre-Chemins).

[2] Founded by art critic Julius Meier-Graefe at the end of 1899, this gallery dedicated to modern decorative art competed with the better-known L’Art Nouveau gallery owned by Siegfried Bing. Two articles by Bertrand Mothes will be published on this subject shortly. [3] For other products, the catalog lists the names of the designers.In this case, it is likely that the contract between the gallery and the designer specified that the latter’s name had to be mentioned.

[4] Another example of this vase has been catalogued and appears in the book “Le génie verrier de l’Europe” (G. Cappa, ed. Mardaga, 1998). Unlike our vase, which is predominantly aquamarine in color, this one is characterized by colorless crystal with a gradient of metallic tones, with the “rosathea” and “yellow” shades predominating, while the aquamarine tone is concentrated in the lower third. As this piece is unsigned, it may be a prototype.

[5] See our article on the “guimardization” of stoneware vases produced by Gilardoni & Brault.

Translation: Alan Bryden