The fantastic and colorful bestiary of Castel Béranger

12 January, 2025

The Cercle Guimard has already devoted several articles to the Castel Béranger, the apartment building commissioned by Élisabeth Fournier[1] from Hector Guimard in 1894 and completed in 1898. Our last article [2] showed that the complete stylistic overhaul carried out by Guimard during its construction from 1895 to 1898 coincided with a change in suppliers for the ceramic decorations. This time, we focus on the fantastical and colorful bestiary that adorns its facades, first presenting the unique features of this project, then the fantastical dimension of its decor inspired by nature and the neo-Gothic repertoire. Finally, the materiality and polychromy of this bestiary will be explained.

“This building, […], is set to revolutionize the art of construction. Its appearance is truly extraordinary”[3].

As reflected in these comments made by a journalist in an article dedicated to Castel Béranger, yesterday as today, the facade of this building does not go unnoticed in the public space. The fact that it was one of the winners of the facade competition organized by the Paris City Council in 1898 testifies to the desire of the public authorities at the time to encourage architecture that broke with the monotony of the facades of traditional Haussmann-style apartment buildings, “which made the streets of Paris boring enough to put you to sleep”[4]. Its construction coincided with the work of the commission set up to draw up new road regulations allowing greater freedom in the silhouettes of buildings and their projections.

The Castel Béranger project: modifications and unique features

A design far removed from the initial project

However, this rich decoration, which brought international fame to Castel Béranger and Hector Guimard, was not what the architect had originally planned. A look at the facade elevations in the building permit application submitted by Guimard in March 1895 reveals an initial design that was never realized. After his stay in Brussels in the summer of 1895, during which he met architects Victor Horta (1861-1947) and Paul Hankar (1859-1901), Guimard redesigned the entire interior of Castel Béranger. This is how a fantastic and colorful bestiary appeared on the facades, but also inside the building.

A bestiary on the facade: the only example in Guimard’s work

The term “bestiary” is used here in the same way as it is defined in the Larousse dictionary, namely as “the whole of animal iconography, or group of animal representations”[6]. Looking at the facades of Castel Béranger, it is easy to identify elements of the decor that are rather figurative in nature, inspired by wildlife. The shape of a cat is easily recognizable.

Panel depicting a cat arching its back, made of glazed sandstone from Castel Béranger, created by Gilardoni & Brault in 1897. Photo by Nicholas Christodoulidis.

The central motifs of the cast iron balconies are half human, half feline. Their large noses may even evoke the muzzle of a lion, a recurring motif in 19th-century ornamental cast ironwork.

Central motif of the cast iron balconies of Castel Béranger, produced by the Durenne foundry in Sommevoire between 1895 and 1898. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

However, the bestiary of Castel Béranger also includes several motifs that are more specifically related to underwater fauna and contribute to a broader aquatic repertoire[7] in this apartment building.

The most convincing example is undoubtedly the decorative cast iron chain anchors, whose formal appearance resembles that of a seahorse. These structural elements, which appear numerous times on the facades, are the ends of tie rods that contribute to the chaining of the construction, allowing the distribution of tensile forces in the masonry and the solidarity of the walls (and possibly the floors) between them. It is for this reason that Guimard added what could be described as two legs to these sea horses.

Cast iron anchor from Castel Béranger, made by the Durenne foundry in Sommevoire between 1895 and 1898. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

Inside, the starting point of the staircase handrail may also evoke the silhouette of a horse’s head and neck[8].

Start of the handrail on the staircase of the building on Rue du Castel Béranger, carved wood. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

Once again outside, on a tympanum of the building overlooking the courtyard facing the hamlet of Béranger, there is a fish between two shrimps.

Glazed ceramic tympanum on the courtyard façade overlooking the hamlet of Béranger, created by Gilardoni & Brault between 1895 and 1898. Photo by Nicholas Christodoulidis.

This decorative animal register is an exception in Guimard’s work. Although some cast iron elements from Castel Béranger were later reused by the architect in some of his other projects[9], no other decoration of such magnitude featuring fauna preceded or followed it in his built work.

The fantastical decoration of Castel Béranger

A fantastical dimension…

Castel Béranger was not only unique in the diversity of polychrome materials used in its masonry. It was also unique in the profusion of chimeras adorning its facades, a veritable fantastical bestiary. According to the Larousse dictionary, the fantastic “refers to an artistic work […] that transgresses reality by referring to dreams, the supernatural, magic, and horror[10].”

This “transgression of reality” is a key concept in understanding the decoration of this apartment building. Unlike his initial project, in which he had planned a stylized botanical decoration, the architect ultimately designed a decoration that no longer sought to reproduce nature as it appears to us. Instead, it oscillates between a “modified” realism, as in the cast iron seahorses or the cat panel, where the modeling of the animal’s body is extended by three-dimensional curves…

Nicholas Christodoulidis (photographer), Panel depicting a cat arching its back, made of glazed sandstone at Castel Béranger, created by Gilardoni & Brault in 1897. Photo Nicholas Christodoulidis.

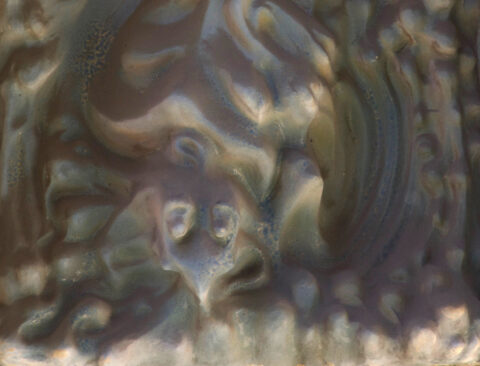

… and a more or less advanced abstraction, such as, for example, on the panel decorating the corbel of the bow window in the courtyard, where the modeling appears so abstract, so shapeless, that at first glance it seems futile to look for any similarities with an element of fauna or flora.

Corbeling of the bow window in the courtyard of Castel Béranger. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

Even if a few imaginative minds will surely cling to a detail in the lower part to see a beak and two eyes.

Detail of the glazed ceramic panel on the corbel of the bow window in the courtyard of Castel Béranger, created by Gilardoni & Brault between 1895 and 1898. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

In Études sur le Castel Béranger, written in 1899 by Georges Soulier and a certain “P.N.”—probably Paul Nozal—the authors explain that “the designs of the ornamentation [must] accompany the living decor […], in a harmony of more fluid forms”[11], without competing with it. We can therefore assume that for Guimard, the essential thing was not to reproduce nature but rather to evoke it through more or less precisely shaped contours[12].

Georges Soulier and Paul Nozal also point out that over the centuries, art has very rarely sought to imitate nature scrupulously and that transgressing reality is therefore nothing new. The foliage, the stylization of acanthus leaves on Corinthian capitals, and the chimeras adorning cathedrals are perfect examples of this.

Symmetrical ornamental scrollwork, 1527, engraving. Louvre Museum, Department of Graphic Arts, 8324 LR

Corinthian capital, 1650-1700, Cour Carrée, sculpture. Louvre Museum, Department of Medieval, Renaissance, and Modern Sculpture, RF 4149.

…inspired by nature…

Some of these decorations, which transcend reality, can be spontaneously likened to natural organisms, but this time without it being possible to identify them with certainty as an animal species. Each viewer forms their own idea of what they see, based on their own culture. This is the case with the mass-produced ceramic metopes that adorn the metal lintels found numerous times on the façade. Their shape may, for example, vaguely resemble that of a frog’s head or an insect, such as a praying mantis.

Metopes of the metal lintels of certain bays, made by Gilardoni & Brault in glazed ceramic (or by Bigot in glazed stoneware) between 1895 and 1898. Photo Nicholas Christodoulidis.

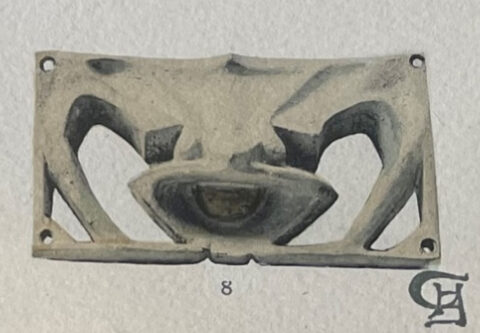

The air intakes on the facades are decorated with cast iron grids whose shape could be likened to that of a crab, or even a mouth and two nostrils[13].

Air vent, portfolio Le Castel Béranger, work by architect Hector Guimard, Paris, Librairie Rouam, 1898, pl. 22. Library of the Museum of Decorative Arts, Reserve P95.

In the apartments, the wallpaper specifically designed for the antechambers also features a pattern highlighted by its coloring, with whimsical lines reminiscent of those of a feline.

Left: detail of wallpaper in the antechambers, portfolio Le Castel Béranger, work by architect Hector Guimard, Paris, Librairie Rouam, 1898, pl. 30. Private collection. Right: detail of a fragment of wallpaper produced by Le Mardelé, kept at the Bibliothèque Forney, ref. 998, three tones including gold, circa 1895–1896. Photo: F. Descouturelle.

Unique among the other wallpapers designed for other rooms in Castel Béranger, its overall composition evokes a tree of Jesse, while the style of this particular motif is reminiscent of a medieval illumination, which brings us to the most intriguing aspect of this bestiary.

… and a medieval phantasmagoria

Another interpretation of the animal repertoire present at Castel Béranger is the one that earned it the nickname “house of devils” in Auteuil, as reported by Jean Rameau in Le Gaulois in 1899.

“The artist may have wanted to represent chimeras, but the common people see demons, causing all the old women in the district to cross themselves from twenty paces away. There are devils at the doors, devils at the windows, devils at the cellar windows, devils on the balconies and stained glass windows, and I am assured that inside, the stair railings, stove knobs, cupboard keys, everything from the large living room to the pantry, is the same devilry. If God no longer protects France, at least the devil seems to protect Auteuil. Parisians, sleep in peace[14].

Even if Jean Rameau exaggerates, his use of vocabulary associated with horror and hell clearly indicates that there is a “satanic” dimension to Castel Béranger. He even seems to have had a fairly detailed knowledge of the building, since he mentions the presence of devils on the stove knobs. However, as evidenced by a detail in the illustration of the kitchen stove facades published in the Castel Béranger portfolio, the motif between the two air intake panels on the cast iron facades perfectly evokes a diabolical figure with an oversized, toothy mouth and furious eyes above it.

Stove in the kitchens of Castel Béranger, portfolio Le Castel Béranger, œuvre de Hector Guimard architecte, Paris, Librairie Rouam, 1898, pl. 51, no. 4 (detail). Private collection.

The facades of Castel Béranger feature several elements—particularly the gables and the relative asymmetry of the street-facing facade—that link the building to medieval architecture and justify its name, “castel.” This is hardly surprising given the renewed interest in Gothic architecture in the 19th century, but also the connection between Eugène Viollet-le-Duc and Hector Guimard. However, his “satanic” decorative repertoire, while certainly present, is not as prominent as Jean Rameau would have us believe. In reality, Guimard does not simply take the Middle Ages as his source, but refers to the phantasmagorical image of the witch, which, as Maryse Simon[15] explains, is wrongly linked to the medieval period, since in reality the witch hunt was at its peak in the 16th and 17th centuries. This phantasmagorical image of the medieval witch stems from a construct that began in the modern era and was modified in the 19th century, notably by authors of fairy tales such as the Brothers Grimm[16].

This pastel by Lévy-Dhurmer, created in 1897—during the construction of Castel Béranger (1895-1898)—depicts a witch surrounded by all her attributes: a cat, a snake, a lizard, a bat, and an owl. With the exception of the owl, all of these creatures can be found on the facades of Castel Béranger.

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, The Witch, 1897, pastel on paper. Musée d’Orsay, RF 35503.

The panel depicting the cat arching its back was made of glazed stoneware before May 1897 by Gilardoni & Brault, based on the work of modeler Xavier Raphanel.

Panel depicting a cat arching its back (detail) in glazed sandstone from the Castel Béranger, created by Gilardoni & Brault in 1897. Photo by Nicholas Christodoulidis.

The scan carried out by Nicholas Christodoulidis identified the figure located at the intersection of the pediments of the dormers on the top floor overlooking Rue Jean-La-Fontaine. This chimera carved in stone, despite its bulging eyes, resembles a bat with its pair of membranous wings.

Castel Béranger seen from Rue La Fontaine, 1895–1898. The bat is framed in red.

Photo by Arnaud Rodriguez.

3D printing of the chimera located at the intersection of the pediments of the dormers on the top floor of the façade of Castel Béranger on Rue Jean-de-La Fontaine. Photogrammetry and 3D modeling by Nicholas Christodoulidis.

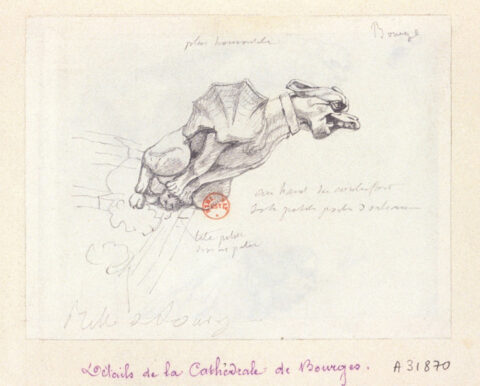

The use of these types of creatures was common during the Gothic and Neo-Gothic periods, as evidenced by the gargoyles on Bourges Cathedral (12th-13th centuries) and Viollet-le-Duc’s gallery of chimeras on Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris (mid-19th century).

“Details of Bourges Cathedral,” pencil drawing. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Prints and Photography Department, EST RESERVE VE-26 (M).

The pattern of the air vents, presented above, can also evoke the shape of a spider. In addition to the fact that this insect is also linked to the image of the medieval witch, in the Middle Ages the symbol of the spider was associated with the plague because it was believed that they wove numerous webs in the homes of the deceased[17].

Cast iron air vent from Castel Béranger, made by the Durenne foundry in Sommevoire between 1895 and 1898. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

With their sinuous shape, the cast iron grab bar supports can resemble snakes.

Cast iron crossbar from Castel Béranger, made by the Durenne foundry in Sommevoire between 1895 and 1898. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

As for the fantastical figures wrapped around the stone columns of the entrance gate, they resemble lizards or small dragons.

Sculpted column from the entrance gate of Castel Béranger, 1895–1898. Photo by F. Descouturelle.

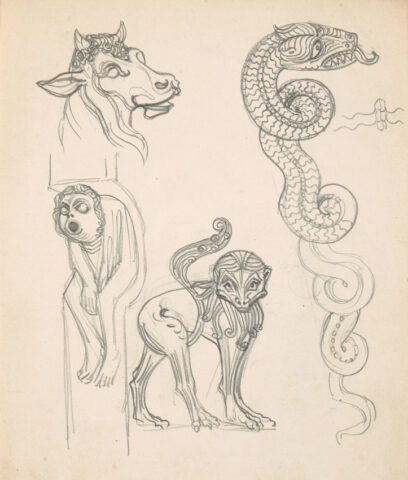

The depiction of these reptiles can also be explained by artists’ keen interest in the Orient in the 19th century. Victor Hugo even wrote in the preface to the collection Les Orientales that “people are much more interested in the Orient than they ever have been. […] In the age of Louis XIV, people were Hellenists; now they are Orientalists[18].” The snake is therefore a recurring motif in the works of this period, as evidenced by this drawing by Eugène Grasset (1845-1917).

Eugène Grasset (illustrator), Heads of a monkey, bovine animal, and snake, pencil, created between 1890 and 1903. Musée d’Orsay, ARO 1993 9 2 354.

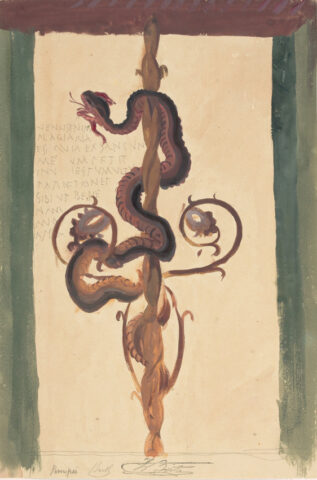

As well as this draft of a decorative panel by architect Louis Boitte (1830–1906), kept at the Musée d’Orsay.

Louis Boitte, Panel decorated with a snake coiled around a braid, pencil and gouache on paper mounted on paper, created between 1890 and 1903. Musée d’Orsay, F 3457 C 673.

Finally, when you look at the street facade of Castel Béranger, you can’t miss the cast iron masks that adorn the railings. These are undoubtedly what earned this apartment building the nickname “house of devils,” as they feature the attributes of the demon Mephistopheles—a character from the legend of Faust—namely a moustache, a goatee, and almond-shaped eyes. The presence of these figures on the façade is not surprising in light of what we have just seen, since witches are associated with the figure of Satan[19].

Central motif of the cast iron balconies at Castel Béranger, produced by the Durenne foundry in Sommevoire between 1895 and 1898. Photo: F. Descouturelle.

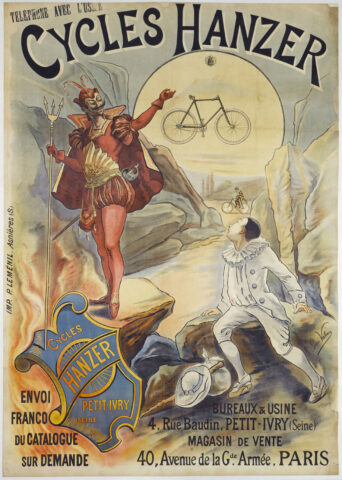

Léon Valentin (illustrator), J. Proust (illustrator-lithographer), Paul Lemenil Printing House. Cycles Hanzer, 40, avenue de la Grande Armée, Paris, poster, color lithograph, circa 1895. Paris, Musée Carnavalet.

The combination of this human figure with two legs above its head also echoes the grylles, grotesque creatures from antiquity, which were reused at the end of the Gothic period and during the Renaissance. The king’s staircase at the Château de Villers-Cotterêts features several examples of this.

Grylle on the cornice of the King’s staircase at Villers-Cotterêts Castle. Photo Eliselfg, Wikimedia Commons (detail).

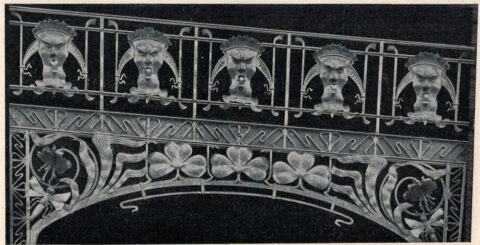

These masks adorning the railings of Castel Béranger clearly influenced German architect Felix Reinhold Voretzsch. He designed a very similar model—albeit in a burlesque style, as the masks here stick out their tongues—to decorate the railings on the third floor of the loggia of the Art Nouveau building at Bürgerwiese 20, built in Dresden in 1900.

Balustrade of the loggia at Bürgerwiese 20 in Dresden, architect Reinhold Voretzsch, portfolio Modern Artistic Ironwork, 1902, pl. 98. Private collection.

Colorful chimeras

Colors and materiality

The variety of materials used on the facades of Castel Béranger, and the resulting polychromy, is very striking. As mentioned in the introduction, it clearly distinguishes the building from the neighboring apartment buildings. The photograph on plate thirteen of the Portfolio du Castel Béranger, colored using the “watercolor facsimile” process, shows the inner courtyard opening onto the Hameau Béranger. The variety of materials used by Guimard and the resulting polychromy are clearly visible. If we count only the materials used for the masonry, we arrive at a total of seven: millstone, terracotta or glazed brick, sand-lime brick, cut stone, cast iron, and sheet metal. This polychromy is not a whim of the architect but the result of rational thinking that illustrates the connection between Viollet-le-Duc and Guimard.

During the symposium dedicated to Hector Guimard, organized by the Musée d’Orsay as part of the 1992 exhibition devoted to the architect, Lanier Graham emphasized the considerable influence that the rationalist school initiated by Viollet-le-Duc had on architects at the end of the 19th century, particularly Hector Guimard[20]. For Viollet-le-Duc, form had to derive from function and structure, and materials had to be used and combined according to their specific qualities[21]. The most compelling example of the connection between the two architects is undoubtedly the main building of the École du Sacré Cœur, where Guimard used the sloping cast iron columns designed by Viollet-le-Duc for the “XIIe Entretien”, dedicated to masonry, published in the book Entretiens sur l’architecture[22]. This influence is particularly due to Guimard’s training, as his teachers, Charles Génuys and then Gustave Raulin, were part of the rationalist school and were both disciples of Viollet-le-Duc. Marie-Laure Crosnier Leconte points out in the 1992 exhibition catalog[23] that during Guimard’s lecture at the Figaro offices on May 12, 1899, he repeatedly stated that the author of the Entretiens was his mentor[24].

Like Viollet-Le-Duc, Guimard therefore strove to use the right materials in the right places in order to make the most of their qualities while keeping the budget under control. He applied this principle both to the construction of the Castel Béranger and to its ornamentation. Guimard chose to use cast iron and ceramics to create the fantastical bestiary we have just described. Both materials have the advantage of being highly malleable, making it easy to create zoomorphic shapes, with the cast iron being poured and the ceramics stamped into molds. These techniques are also perfectly suited to the low-cost mass production of pieces.

Ceramics is a material that is designed to be glazed. In addition to protecting the pieces, the glaze has the advantage of coloring them according to the designer’s wishes. At Castel Béranger, Guimard chose to coat most of the ceramic chimeras with a glaze in a more or less dark bluish-green hue[25]. The cast iron bestiary (seahorses, spiders, snakes) was covered with paint, also in a bluish-green shade, to create harmony between the elements of the finishing work that make up this fantastical bestiary. It is likely that the balcony masks were gilded, as suggested by the portfolio plates.

Balcony on the fourth floor of the courtyard façade of the Castel Béranger building, portfolio Le Castel Béranger, œuvre de Hector Guimard architecte, Paris, Librairie Rouam, 1898, pl. 16. Private collection.

The perishable nature of this coating and the maintenance it requires may explain its disappearance. However, it should be borne in mind that the photographs in the portfolio were taken in black and white and then colored with watercolors. We know that Guimard took certain liberties with reality in this portfolio and that he may have chosen to depict these masks as gilded, even though they may have originally been covered with a bluish-green paint.

A collaboration between Guimard and renowned art manufacturers

The preparatory drawings produced by Guimard for all these decorations were brought to life by two sculptors, Raphanel and Ringel d’Illzach, who are mentioned by Guimard in the list of suppliers who participated in the construction of the Castel Béranger, a list that appears at the beginning of the portfolio published in 1898[26].

We know that the casting was entrusted to the Sommevoire factory of the Durenne foundry, the main site of the establishment, as indicated in an advertisement published in the Bulletin municipal officiel de la Ville de Paris on November 21, 1900. The quality of its products was recognized worldwide, thanks in particular to the numerous prizes it won at various national and international exhibitions. The journal of the 1896 National and Colonial Exhibition in Rouen even mentions that “the Durenne company has no more awards to expect. After appearing in countless exhibitions, each time adding a new medal or diploma to its already impressive collection, it has been out of competition since the 1889 Paris World’s Fair[27].”

The exterior architectural ceramics that enliven the facades were attributed to the Gilardoni & Brault tile factory[28]. In parallel with the Castel Béranger project, this company collaborated with Guimard on the design of his stand at the 1897 National Ceramics Exhibition, as illustrated by postcard no. 7, Le Style Guimard. Of particular note is the presence of the future decorative panel of Castel Béranger featuring a cat arching its back, at the top right of the façade. Like Durenne, Gilardoni & Brault was an extremely well-known establishment, even described as “first-rate”[29], whose trademark mechanical tiles “[were] recognized by builders as indisputable “[30]. The Gilardoni & Brault factory, for example, received gold medals at the Universal Expositions of 1889 and 1900[31].

Thus, this decorative project, very different from the one initially planned by the architect before his trip to Belgium, brings into play more or less figurative elements unified by their materiality. Mainly made of glazed ceramic or painted cast iron, their colors range from green to blue and ochre, adding to the polychromy of the various materials used for the masonry.

The plurality of sources that Guimard drew on to compose this fantastical bestiary (Neo-Gothic, Neo-Renaissance, Orientalism, fauna and flora) produced a heterogeneous decor that sets it apart from the work of the two other main initiators of European Art Nouveau: Horta, whose style was much more homogeneous from the outset but who neglected certain aspects of fixed decoration such as wallpaper, and Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926), whose work was cluttered with Christian symbolism. In this first complete work of modern art in France, the bestiary of Castel Béranger, as well as the abstract motifs that accompany it, transcends a building inspired by Viollet-le-Duc’s rationalism with its disturbing strangeness.

Maréva Briaud, Doctoral School of History at Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University (ED113), IHMC (CNRS, ENS, Paris 1).

Notes

[1] Élisabeth Fournier was a bourgeois woman from the Auteuil neighborhood, a widow, eager to invest her capital in real estate.

[2] M. Briaud, “Hector Guimard and Muller & Cie at Castel Béranger: the end of a collaboration,” Le Cercle Guimard [online], November 8, 2024.

[3] Le Monde illustré, April 8, 1899.

[4] L. Morel, “L’Art nouveau,” Les Veillées des chaumières, May 17, 1899, p. 453.

[5] Established in June 1896 by the Prefect of the Seine, Justin de Selves, this commission, chaired by architect Paul Sédille, had as its rapporteur the architect Louis Bonnier, who was very favorable to Guimard. Its work resulted in new road regulations, published in the form of a decree in 1902.

[6] “Bestiary,” Larousse Dictionary [online], accessed 11/19/24. URL: https://www.larousse.fr/dictionnaires/francais/bestiaire/8916

[7] The whip-like lines of the mosaics on the floors of the vestibule and halls evoke seaweed, and the vestibule with its glazed sandstone walls has sometimes been compared to an underwater cave.

[8] Shortly afterwards, the ends of the cast iron arches of the uncovered metro surrounds would also take on this stylized shape of a seahorse’s head.

[9] This is the case with the balcony railings reused at the Roy Hotel (1897-1898), as well as the crossbar supports also reused at the Roy Hotel and the Guimard Hotel (1909-1912).

[10] “Fantastic,” Larousse Dictionary [online], accessed on 19.11.24. URL: https://www.larousse.fr/dictionnaires/francais/fantastique/32848

[11] G. Soulier and P. N., Études sur le Castel Béranger, œuvre de Hector Guimard, 1899, p. 13.

[12] Here we recall the similarity between Guimard’s early style and the 17th-century auricular style mentioned in Michèle Mariez’s article published on our website.

[13] Which could illustrate their ventilation function.

[14] J. Rameau, “Maisons Modernes,” Le Gaulois, no. 6323, April 3, 1899, p. 1.

[15] M. Simon, “La sorcière moyenâgeuse faussement médiévale ? Construction d’une image fantasmagorique” in É. Burle-Errecade, V. Naudet (eds.), Fantasmagories du Moyen Âge, Presses universitaires de Provence, 2010, pp. 201-208. URL: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pup.2135.

[16] M. Simon, op. cit., pp. 201-208.

[17] G. Tempest, “L’araignée,” Historia [Online], February 14, 2019, https://www.historia.fr/societe-religions/vie-quotidienne/laraignee-2064996.

[18] V. Hugo, Les Orientales, Paris, J. Hetzel, 1829, p. 7.

[19] M. Simon, op. cit.

[20] L. Graham, “Guimard, Viollet-le-Duc et le modernisme,” in Guimard. Colloque international, musée d’Orsay, 12 et 13 juin 1992, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994, p. 20.

[21] Ibid., p. 21.

[22] E. Viollet-le-Duc, Entretiens sur l’architecture. Atlas, Paris, A. Morel et Cie, 1863, pl. XXI.

[23] M.-L. Crosnier Leconte, P. Thiébaut, Guimard, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 1992, p. 78

[24] Le Moniteur des arts, July 7, 1899, pp. 1465-1471.

[25] The ceramic tympanum on the fourth floor of the building’s facade overlooking the courtyard is covered with ochre enamel.

[26] H. Guimard, Le Castel Béranger, œuvre d’Hector Guimard, Paris, Librairie Rouam, 1898.

[27] “Les jardins,” Journal de l’Exposition nationale et coloniale de Rouen et moniteur des exposants, 1896, no. 7, p. 3.

[28] However, it is possible that the manufacture of the ceramic metopes decorating the metal lintels was entrusted to Alexandre Bigot.

[29] “Les Grandes industries. La tuilerie de Choisy-le-Roi,” Journal de l’Exposition nationale et coloniale de Rouen et moniteur des exposants, 1896, no. 14, p. 4.

[30] Ibid, p. 4.

[31] Exposition Universelle de 1900 à Paris. Liste des récompenses, classe 72, céramique, p. 852, Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1901.

Translation : Alan Bryden