Hector Guimard’s participation in the 1925 Exhibition of Decorative Arts– Part 1

7 September 2025

We are taking advantage of the celebrations marking the centenary of the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, held in Paris in 1925[1], to publish our research on Hector Guimard’s participation in this event. The architect’s relatively modest contribution is somewhat reflective of his career in the aftermath of the First World War. This period has ultimately been little studied, but the 1925 Exhibition was one of its highlights and undoubtedly one of its most interesting moments. Guimard’s participation took the form of three works in one of the exhibition’s sections called the French Village: the town hall and two funerary monuments. While we have a comprehensive study of the French Village currently underway, we have chosen to highlight some lesser-known aspects, such as the interiors of the town hall and the cemetery. We will begin by discussing the context that led to the organization of the exposition, Guimard’s role, and his participation in the debate of ideas on the eve of this major event for the decorative arts and architecture.

Driven by Art Nouveau in the 1890s, the revival of European architecture and decorative arts that began in the late 19th century reached maturity around 1910, then continued into the 1920s with what would retroactively be called the Art Deco style, reaching a spectacular climax in France with the 1925 Exhibition. The long gestation period of this event—which began twenty years earlier and was postponed several times, notably due to the First World War—was commensurate with its success (more than 16 million visitors) and its international impact, propelling France to the forefront of nations in this field.

The organizers’ stated ambition was to exhibit only new and modern works[2], so no space was given to older styles, which were confined to exhibitions outside the event, such as the one organized at the Galliera Museum[3]. Even though some observers recognized the contribution of the 1900 artists to modern art, the break with Art Nouveau was already largely complete. Among a few famous statements, that of the painter Charles Dufresne (1876-1938) summed up the general mood of the time quite well: “The art of 1900 was the art of fantasy, that of 1925 is the art of reason” … With a few exceptions, critics were therefore fierce towards Art Nouveau, often dwelling on its excesses and quickly forgetting that the architecture and decorative arts celebrated with pomp and circumstance in 1925 drew in part from the renewal that had begun thirty years earlier. It would take a decade before interest in Art Nouveau was rekindled and its rehabilitation and protection began to be considered[4].

Official poster for the 1925 Exhibition Priv.coll.

In 1925, among the names of participants who took advantage of the event to launch or consolidate their careers, such as Mallet-Stevens, Le Corbusier, Roux-Spitz, and Patout, others were already active on the art scene in the 1900s. A sign of a certain recognition, the presence in 1925 of Plumet, Sauvage, Dufrène, Follot, and Jallot was also proof of their ability to adapt and renew themselves. Two of them, Maurice Dufrène (1876-1955) and Paul Follot (1877-1942), were even at the head of decoration workshops in Parisian department stores (La Maîtrise at Galeries Lafayette for the former, Pomone at Le Bon Marché for the latter). The success of the high-quality Art Nouveau productions of these two great names in decoration at the turn of the century did not prevent them from shifting towards a more stripped-down style in the mid-1900s and then, in the 1910s, towards compositions in which curves had almost disappeared.

Hector Guimard’s situation was somewhat different from that of his colleagues. Although he had evolved his style towards greater simplicity and sobriety, he always refused to give in to fashion. On the eve of the 1925 Exhibition, he told a newspaper: “Let’s just be ourselves, impose the discipline of harmony on ourselves, without believing that Fashion can and should dictate Art[5].” We will return to this principle a little later, as it was a guiding principle of the 1920s that largely explains the choices made by the architect during this period.

At the beginning of this new decade, Guimard continued to focus primarily on architectural work, as the loss of his studios in the aftermath of the world war had greatly reduced his work in the field of decorative arts. However, the activism he still displayed in the early 1920s allowed him to retain a certain influence within organizations known for promoting new ideas and heavily involved in the genesis of the 1925 Exhibition. Thus, even though he no longer held any responsibilities within the Société des Artistes Décorateurs (SAD)[6], he was still a member in the early 1920s and even exhibited there in 1923[7]. It should also be noted that during his trip to the United States in 1912, Guimard had been commissioned by the SAD. He introduced himself to the Americans as vice-president of the association and promoter of “The International Exhibition of Modern Architecture and Decoration,” which was to be held in Paris in 1915[8]…

It was therefore as an expert on the subject and spokesperson for modern ideas in the run-up to the exhibition that he became a founding member of the Groupe des Architectes Modernes (GAM)[9], holding the position of vice-president alongside Henri Sauvage (1873-1932), under the presidency of the indispensable Frantz Jourdain (1847-1935).

Letter from the Groupe des Architectes Modernes requesting the fee of 40 F from its members, dated 10 March 1928 and signed by Boileau. Coll. MOMA. All rights reserved

In the same interview in 1923, he justified its creation by the need to promote modern ideas that would undoubtedly be expressed during the upcoming event and, aware that the pavilions built would only have a short-lived existence, by the need to create an annex outside the 1925 Exhibition sponsored by the French State and the City of Paris “where modern architecture would be expressed, like jewelry, furniture, and fabrics, in definitive materials. These buildings would provide modern decorators with a living setting and industrialists with an initial outlet for their modern production, without which a reaction would be to be feared. Most of the pavilions built for the exhibition were indeed destroyed after the event, and this annex project never saw the light of day, nor did the ambitious project entitled “Travelers’ Hotel/American House/ Investment Buildings, permanent constructions for visitors to the 1925 Decorative Arts Exhibition,” which we know existed from three plans signed by several GAM architects, including Guimard, and which was to be located on Boulevard Gouvion-St-Cyr in Paris (75017).

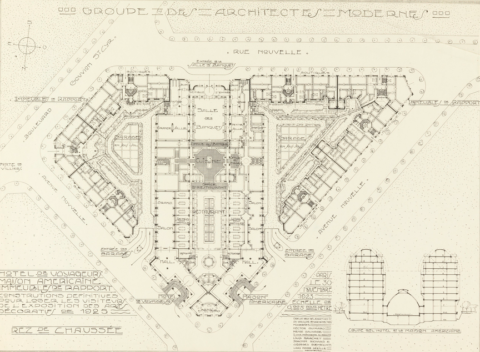

Plan of the ground floor of the final building design by the Groupe des Architectes Modernes for the 1925 Exhibition, dated November 30, 1923. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. All rights reserved..

The GAM was ultimately entrusted with the creation of a section called the French Village within the exhibition. This could be seen as compensation, or even a way of keeping it at arm’s length, but the fact that several of its members were tasked with constructing some of the most important buildings at the event nevertheless confirms the association’s influence on the exhibition.

The French Village Town Hall

The French Village occupied a relatively small area around Cours Albert 1er, slightly away from the Esplanade des Invalides, which was considered the epicenter of the exhibition. Comprising some twenty buildings designed by as many architects from the GAM[10], the complex was a kind of architectural proposal intended to represent a village from the early 20th century.

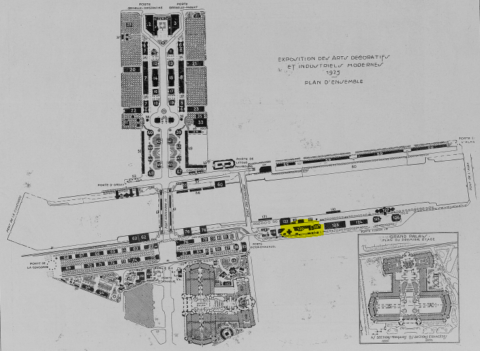

Plan d’ensemble de l’Exposition de 1925 implantée de part et d’autre de la Seine. L’emplacement du French Village est surligné en jaune. La Construction Moderne, 03 Mai 1925. Coll. part.

In addition to the essential town hall, church, and school, there was an inn, a “bourgeois” residence, a community center, a bazaar[11], various commercial buildings, and several so-called secondary structures such as electrical transformers, a sanitary unit, and a wash house. Without exception, all these structures shared the common feature of having been built in a modern style.

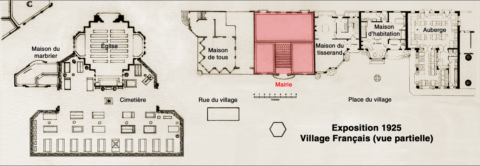

Partial plan of the French Village based on plans from the portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Rassemblés par Pierre Selmersheim, published by Charles Moreau, 1926. Photomontage by F. D.

For economic reasons and due to constraints related to its environment, the ambition of the initial project had been scaled back. The architects had to work around existing plantings and connections to the sewer, water, gas, electricity, and telegraph systems. Furthermore, as the area ultimately allocated to the project did not allow for the construction of independent buildings, Dervaux had no choice but to make the buildings adjoined (with the notable exceptions of the church and the school). Most of them were therefore aligned lengthwise, parallel to the Seine. This revision of the initial project had the immediate effect of changing the name of the complex from “Modern Village” to “French Village,” as the GAM architects had been unable to demonstrate sufficient urban planning skills. It should be noted that this double name persisted, even during the exhibition, as some authors felt that the small village was modern enough to retain this description.

The Guimard town hall was one of the last buildings in the village to be completed (along with Pierre Patout’s (1879-1965) electrical transformer), even though the exhibition had been open for over a month[12]. Several old postcards show the building still under construction, despite the photographers’ efforts to hide it or relegate it to the background…

View of the French Village. In the background on the left, the town hall under scaffolding, as well as the Patout transformer on the right may be seen, ancient postcard. Private collection.

This delay in the construction of one of the main buildings in the small town probably explains its late inauguration. It was not until Monday, June 15, 1925, that the French Village was inaugurated, as shown in a photo in the Excelsior newspaper, in which the town hall appears to be free of scaffolding.

The inauguration of the French Village, Excelsior, 16 Juna, 1925 Bnf/ Gallica

With its back to the river, Guimard’s town hall stood at the edge of the village square, adjoining the” Maison de Tous” on its left, designed by the talented urban planner D. Alfred Agache (1875-1959), and the “Maison du Tisserand” by architect Émile Brunet (1872-1952) on its right. Agache perfectly summed up the spirit that guided the GAM in the construction of this complex: “(…) the “Village de France”, which we built in order to provide a snapshot of what a rural community should be, to meet the needs of modern life[13].”

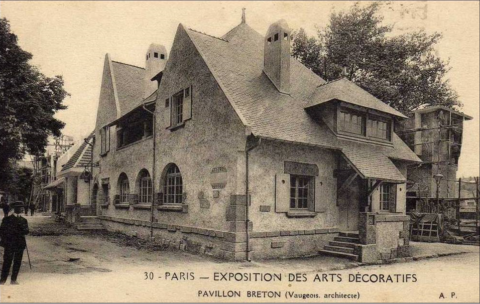

The townhall of the French Village, ancient postcard Private collection .

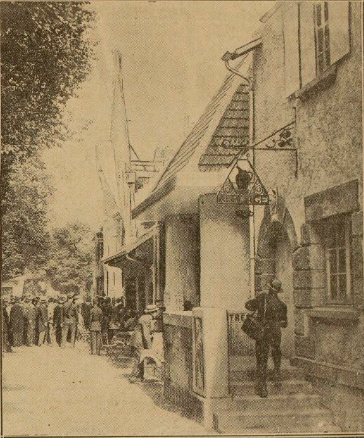

Recognizing that they had been unable to construct separate buildings, the two architects took advantage of this immediate proximity to create an opening allowing circulation between the two structures[14], no doubt believing that the functions and roles of the two buildings were compatible and complementary.

The “Maison de Tous” and the Town hall of the French Village, ancient postcard, private collection

The exterior appearance of the building is well known thanks to numerous old postcards on which it is either the main subject or a secondary subject, with the eleven pinnacles punctuating the roof often making it impossible to miss in photographs. The building appears to be a synthesis of Guimard’s last pre-war works and his research in the early 1920s to develop an economical construction method called “Standard-Construction”, which was used to build the small hotel on Square Jasmin in the 16th arrondissement of Paris.

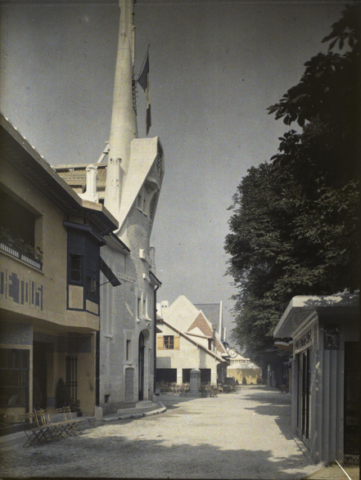

Adding a touch of originality to the group of buildings, the highest of these pinnacles rose directly above the central bay of the slightly curved main facade, punctuated by numerous openings, but set back from a cement canopy covering the clock. Like a signal, both in terms of its height and its function as a carillon, it symbolically rivaled the bell tower of the neighboring church built by architect Jacques Droz (1882-1955) and reminded visitors of the importance of republican life in a modern village… We also have a fairly accurate idea of its colors, as the Archives de la Planète at the Albert-Kahn departmental museum hold numerous autochromes of the event, in which the town hall appears in light tones due to its asbestos brick and white and gray stone cladding[15].

View of the French village. On the left, the Maison de Tous and the town hall, followed by the village square and then the inn; on the right, the fish market, autochrome. Albert Kahn Departmental Museum, Hauts-de-Seine Department

Two other sources are invaluable for learning about the town hall: the portfolio published by Pierre Selmersheim[16] and Anthony Goissaud’s article in La Construction Moderne[17]. A third unpublished article in Le Moniteur des Architectes communaux[18] still eludes us, but we hope that this publication will enable us to find it…

Main facade of the town hall, portfolio Architecture at the 1925 Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts/The Modern Village/Regionalist Buildings and Several Other Pavilions/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim, Charles Moreau Publishing, pl. 2, 1926. Private collection.

A postcard published for promotional purposes by Guimard (used to illustrate the header of this article) completed this editorial material. On the front is an illustration by artist A. C. Webb (1888-1975)[19]. The back comes in different versions depending on the intended use (advertising with a list of town hall employees, promotional material touting a construction technique, or blank for correspondence, etc.).

Rear facade of the town hall, portfolio Architecture at the 1925 Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts/The Modern Village/Regionalist Buildings and Several Other Pavilions/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim, Charles Moreau Publishing, pl. 3, 1926. Private collection

The panels framing the main entrance door, intended for municipal notices, were used here to showcase the companies and artists who collaborated on the town hall project. Among them were some more or less famous names, such as the Schenck family of ironworkers, who made the wrought iron staircase railing, the stained-glass artist Gaëtan Jeannin, who created the stained-glass windows in the wedding hall, and the painter René Ligeron, whom we will discuss later.

Finally, a collection of cast iron pieces from Guimard’s repertoire of models, produced since 1908 by the Saint-Dizier foundry, adorned the building, particularly on the rear facade, where there were balconies on the first floor and panels decorating the windows on the ground floor.

Details of the rear facade of the town hall decorated with cast iron. Library of Decorative Arts. Gift of Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

At the ends of the two facades, the downspouts from the Saint-Dizier foundry connected to gutters from the Bigot-Renaux foundry. These undecorated gutters were fitted with “outward-angled gutter ornaments” also from the Saint-Dizier foundry, which appear to have been used only here.

Details of the rear facade of the town hall decorated with cast iron. Decorative Arts Library, donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Fixed decoration

Among the companies that played an important role in the interior decoration of the building was ELO[20], whose fiber cement paneling covered part of the interior walls. This company experienced significant growth in the 1920s, when there was high demand for inexpensive decorative elements in all styles. As cost savings were a common denominator in most of Guimard’s buildings, it is not surprising that he called on this company for the town hall, given that the budget was particularly limited[21]. ELO paneling thus joined the long list of new materials (and sometimes new techniques) used by the architect throughout his career. The possibility of modeling them to his style was an additional advantage. Notable examples include the use of Lantillon fiberboard panels covering the ceilings of Castel Béranger, Castel Henriette, Villa Berthe, and the Lantillon pavilion in Sevran, as well as Garchey glass stone, also used at Castel Henriette, and ferrolithe, used on the rear façade of the Pavillon de l’Habitation in 1903 [22].

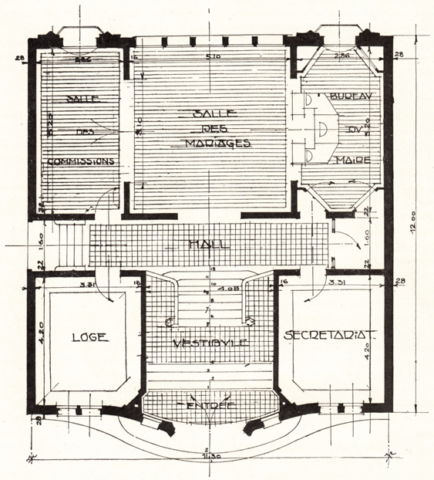

Plan of the town hall published in La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925. Private collection.

An exhibition devoted to the new materials and techniques used in the construction of the town hall occupied the large room on the ground floor, accessible only through two doors at the rear. Among those featured were Taté for plaster, stone, and marble; Lambert Frères for asbestos bricks; and the Société de Traitement Industriel des Résidus Urbains (Industrial Urban Waste Treatment Company)[23].

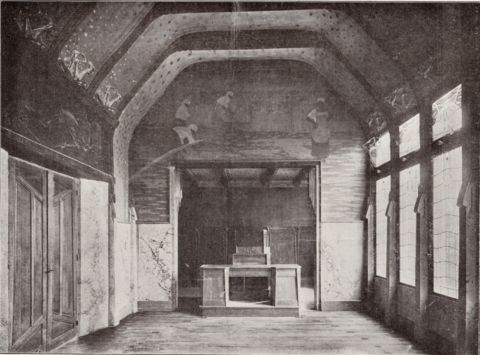

In the photo from La Construction Moderne, we can see ELO paneling covering part of the wall behind the mayor’s desk.

Wedding hall with the mayor’s desk in the background and Jeanneau stained glass windows on the right. La Construction moderne, November 8, 1925. Private collection.

Public collections, meanwhile, hold another photograph that allows us to appreciate the wood paneling sculpture in the foreground.

Wedding hall and the mayor’s desk. GrandPalaisRmnPhoto. All rights reserveds.

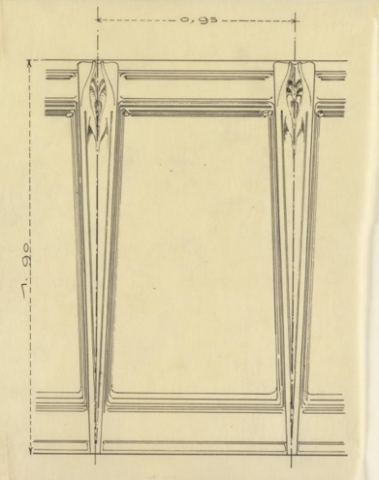

Finally, the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum holds the original and almost definitive design for the paneling. A subtle and delicate blend of the organic and plant worlds, the main motif takes us back twenty years, bringing a touch of sentiment dear to Guimard and open to interpretation.

Drawing of the town hall paneling. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. All rights reserved.

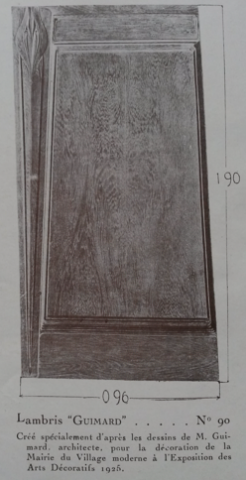

This paneling would appear under the name “Lambris Guimard” in the following year’s ELO catalogs. This was probably the architect’s last attempt to market a model commercially.

« Lambris Guimard », catalogue of the ELO company, 1926. Coll. part.

ELO is also likely the maker of the striking bas-relief featuring vultures above the doors to the wedding hall, signed by Raymond Andrieux. Although birds of prey—alongside wild animals—were among the favorite subjects of artists of the time, one might wonder why they were chosen to adorn the wedding hall.

Detail of the frieze depicting vultures by R. Andrieux decorating the wedding hall. GrandPalaisRmnPhoto. All rights reserved.

Although Guimard undoubtedly met this virtually unknown artist through the ELO company—or perhaps it was the other way around—he may have wanted to seize the opportunity to promote a young artist while adapting an existing work at minimal cost. Information about Raymond Andrieux is very scarce[24], but we have found a trace of a work, now in a private collection, whose resemblance to the bas-relief at the Town Hall is particularly striking.

ELO panel with vultures signed R. Andrieux on the lower right and bearing the ELO company stamp on the reverse, width 1.37 m, height 1.15 m, depth 0.18 m. Private collection.

Our investigation led us to the 1924 Salon des Artistes Français, where Andrieux exhibited a panel in the Decorative Arts category under the caption: “Vultures, fiber cement panel”[25]. This work therefore certainly served as a model for the bas-relief in the wedding hall, with Guimard probably asking the young artist to draw inspiration from his 1924 work and adapt it into a frieze. It is even possible that this work appeared in the manufacturer’s catalog, but the copies we have do not mention it.

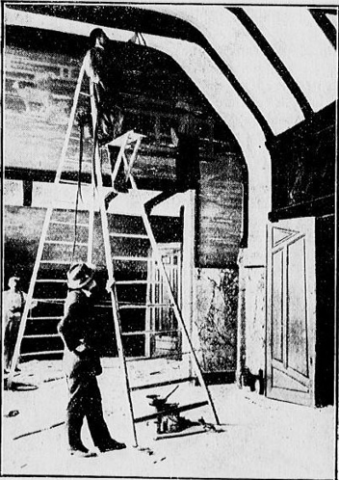

Among the other artists who collaborated on the interior decoration of the building was René Ligeron (1880-1939)[26], whose two paintings depicting scenes of the French countryside—a decorative theme found in many town halls—adorned the walls of the gables of the wedding hall. Thanks to the previous photos, we were familiar with the painting entitled Harvesters binding sheaves. A third, previously unseen view of the wedding hall being decorated gives a glimpse of the second work, entitled Woman guarding sheep, in the same rural style as the first.

The wedding hall of the town hall of the French Village under decoration Recherches et Inventions n° 163, mars 1928. Private collection

It is not impossible that the figure in profile with a gray beard, wearing a hat and standing on a ladder, is Hector Guimard himself, who came to supervise the work…

(to be continued)

Olivier Pons

[1] The event took place from April 28 to November 8, 1925. For convenience, we will refer to it as the 1925 Exhibition or simply the Exhibition.

[2] The rules stipulated: “(…) works of new inspiration and genuine originality, executed and presented by artists, craftsmen, industrialists, designers, and publishers, and falling within the scope of industrial and modern decorative arts, are eligible for admission to the Exhibition. Copies, imitations, and counterfeits of ancient styles are strictly excluded.” Exhibition rules. Private collection.

[3] “Exhibition of the Renovators of Applied Art from 1890 to 1910,” Galliera Museum (Paris), June 6 to October 20, 1925.

[4] See the article by Léna Lefranc-Cervo: https://www.lecercleguimard.fr/fr/proteger-le-patrimoine-art-nouveau-parisien-initiatives-et-reseaux-dans-lentre-deux-guerres/

[5] Interview given to L’Information financière, économique et politique, February 19, 1923. BnF / Gallica.

[6] The Société des artistes décorateurs (Society of Decorative Artists) was founded in 1901 on the initiative of lawyer René Guilleré and several other leading figures in the decorative arts. Its aim was to “promote the development of the decorative arts,” as stated in Article 2 of the SAD’s statutes, “approved by order of the Prefect of Police on April 6, 1901.” Private collection.

[7] The catalog failed to mention his name, but his participation in the 1923 SAD is confirmed by several articles. For example, the January 1923 issue of L’amour de l’Art mentions the three tombs presented by Guimard, including “that of the Henri family,” a unique monument that undoubtedly still exists and which we are actively searching for…

[8] See the article: https://www.lecercleguimard.fr/fr/le-premier-voyage-dhector-guimard-aux-etats-unis-new-york-1912/

[9] See the article by Léna Lefran-Cervo: https://www.lecercleguimard.fr/fr/entre-norme-et-liberte-larchitecture-du-point-de-la-vue-de-la-societe-des-architectes-modernes/

[10] It was built under the direction of architects Charles Genuys (1852–1928) and Gouverneur, based on an overall plan designed by Adolphe Dervaux (1871–1945). See Lefranc-Cervo, Léna, Le Village français: une proposition rationaliste du Groupe des Architectes Modernes pour l’Exposition Internationale des arts décoratifs de 1925, research thesis (2nd year of 2nd cycle) supervised by Alice Thomine Berrada, École du Louvre, September 2016.

[11] The bazaar was built based on plans by architect Marcel Oudin (1882-1936) for the Magasins Réunis chain. A specialist in reinforced concrete construction, Oudin had become one of the architects of the Corbin family from Nancy, owners of the Magasins Réunis in eastern France, but also in Paris (Magasins Réunis République, À l’Économie Ménagère, Grand Bazar de la rue de Rennes).

[12] In an original photo dated June 1, 1925, the town hall still appears to be covered in scaffolding.

[13] La Cinématographie française, April 11, 1925. La Maison de Tous, which was initially to be called Maison du Peuple (House of the People) – a name considered too connotative – was undoubtedly one of the most attractive buildings in the Village, both in terms of its architectural design and the ideas behind its conception and deserves a full article.

[14] Le Journal des débats politiques et littéraires, June 17, 1925.

[15] An article devoted to Guimard’s use of bricks is in preparation and will provide a more complete overview of the materials used in the French Village town hall.

[16] Architecture at the 1925 Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts/The Modern Village/Regionalist Buildings and a Few Other Pavilions/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim. Charles Moreau Editions, 1926.

[17] “The Town Hall of the French Village,” A. Goissaud, La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925.

[18] “La Mairie du Village français à l’Exposition,” Le Moniteur des Architectes communaux, 1925, no. 2.

[19] Alonzo C. Webb (1888-1975) was an American painter and engraver who spent his life between the United States and Europe. After studying architecture and fine arts first in Chicago and then in New York, he moved to Europe after World War I and settled in France in the 1920s, where he produced drawings of ancient monuments and landscapes for advertising and to illustrate articles in major national newspapers (including L’Illustration). Guimard may have met him through his wife Adeline, as Webb was part of the small American colony in Paris. After specializing in engraving, he moved to London in the late 1930s, where he died in 1975.

[20] Founded in 1902, ELO had its headquarters and factories in Poissy (Yvelines) and showrooms located at 9 rue Chaptal in Paris’s 10th arrondissement. It offered decorative paneling and fiber cement (a mixture of asbestos and cement) cladding for both interior and exterior use, thanks to its strength, rot resistance, and fire resistance. Manufactured in large quantities, the cladding was designed to imitate wood, bronze, stone, leather, and even ceramic at prices well below those of these materials (Journal Excelsior, May 6, 1925).

[21] The budget allocated to the town hall was 92,000 francs. La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925.

[22] Ferrolithe was a type of coating that imitated stone. Highly resistant and moisture-proof, it was mainly used to renovate and cover exterior walls.

[23] L’Architecture no. 23, December 10, 1925.

[24] Raymond Andrieux was an artist from Lille who became a member of the Société nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1926 in the sculpture category. A trinket tray decorated with a vulture and signed by R. Andrieux was sold at auction in 2016.

[25] Le Grand Écho du Nord de la France, May 21, 1924. BnF/Gallica.

[26] (Jacques) René Ligeron was born in Paris on May 30, 1880, and probably died in Algiers on December 8, 1939. A traveling painter, he was best known for his engravings, with a preference for etchings. A student of Lepeltier, Lefebvre, and Robert-Fleury, he exhibited mainly landscapes and a few portraits at the Salon des Artistes Français from 1905 onwards. In 1936, the press reported on an exhibition in a Parisian gallery showcasing his latest works, notably blackened wooden panels intended to decorate a large dining room, one fragment of which, featuring Japanese-inspired decoration, has recently been rediscovered.