The « Maison Moderne » of Julius Meier-Graefe — Part 3

30 August 2025

The tenuous links between La Maison Moderne and Guimard

Following Bertrand Mothes’ two articles recounting the history and operations of La Maison Moderne, we would like to add some information about the indirect links that existed between this gallery and Hector Guimard, beginning with a few thoughts on how his creations were marketed.

Only a minority of the countless models created by Guimard would have been suitable for sale by an art gallery. Anything that could be considered industrial production, such as cast iron and architectural ceramics or hardware, had to be excluded. However, both furniture and decorative art objects such as vases, lamps, and frames could have been sold through this type of commercial channel. Yet it is easy to see that no art objects designed or modeled by Guimard and then entrusted to a craftsman to be produced as unique pieces or in small series were ever offered for sale at La Maison Moderne or the Bing Art Nouveau Gallery. As Bertrand Mothes showed us in his previous article, at La Maison Moderne, it was usually Julius Meier-Graefe who was responsible for choosing a model presented by an artist and then for its manufacture (and therefore its cost price). However, as at Bing’s, it was possible for certain prestigious brands or artists to deposit their creations in the gallery. The sale of these objects, whose manufacture had already been paid for, therefore generated only a smaller profit shared between the gallery and the designer. However, unlike many artists and decorators, Guimard refused to use the art gallery distribution channel, where his style, which he had wanted to be so distinctive that he gave it his name, would have been anonymized, diluted among multiple expressions of modern decorative art.

He may also have thought that the advantage of having his works permanently displayed in a gallery (which is more effective than occasional exhibitions) could be offset by well-executed media coverage. However, this type of publicity through the press and publications, which had worked very well at the time of Castel Béranger, subsequently became less common and was sometimes even unfavorable to him.

Having chosen to isolate his production from that of others, he could have used a dealer to represent him or even gone so far as to open a store[1]. The first option would again have represented a significant loss of income. As for the cost of running a store, it could have been a deterrent. But above all, Guimard, who was already indeed an entrepreneur, was keen not to appear as a merchant, because of the moral code that architects imposed on themselves, but also because of the business license that would have had to be paid. We know from a lawsuit brought against him, which he won on appeal, that his status as an architect prevailed over that of a merchant. In a dispute with a supplier who claimed that he “combined the practice of his profession with the operation of a veritable industry, that he had manufacturing workshops and stores where he sold various items made under his direction,”. Guimard defended himself by saying that he did not engage in such an activity, but only practiced ”the artistic application and implementation of his knowledge as an architect and his personal taste.”

So Guimard circumvented indirect sales in two ways. First, in a very traditional manner, through direct sales for small production volumes, either by order or at exhibitions. Then, when larger production volumes were expected, he redoubled his efforts not only to have his creations mass-produced but also to have them published. This was not always the case in his early years of artistic creation, and it was only gradually that this approach became widespread, along with the desire to have his designs featured in catalogs. His goal was twofold: to ensure a steady income while working with this wider distribution to promote the “modern style”, and his own style in particular. It should be noted that in most of these catalogs, Guimard’s designs were placed on the same level as the others, just as they would have been on the shelves of an art gallery. And, ultimately, it was the manufacturer who reaped the lion’s share of the profits from the sale. Only in rare cases was he able to obtain the creation of a specific catalog limited to his own designs.

In order to pursue successfully this policy to market his creations, Guimard needed a production unit capable of manufacturing products from start to finish (such as furniture or wooden and plaster frames), or of supplying usable models to a manufacturer, whether a craftsman or an industrialist. He was able to achieve this first Rue Wilhem and then, from 1904 to 1914, Avenue Perrichont prolongée.

Given his great sociability, Guimard did not sever all ties with the art dealers, especially when their commitment to the modern style was sincere and not seen as simply another card to add to an eclectic range of products.

In the article we devoted to the recently acquired Guimard glass vase, we showed that Guimard had collaborated closely with the Cristallerie de Pantin.

Guimard Vase from la Cristallerie de Pantin, height. 40,2 cm. Priv.coll. Photo F. D.

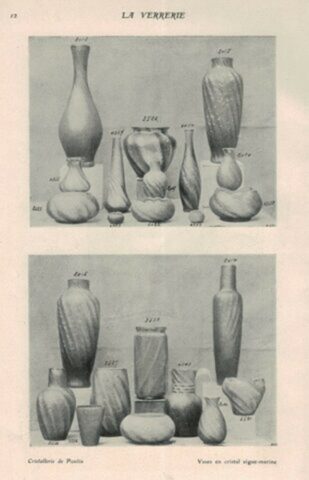

This crystal manufacturer presented a selection of “aquamarine” vases in the gallery of La Maison Moderne, presented in the catalog published in 1901.

« Crisallerie de Pantin/Aquamarine vases . Documents from L’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (La Maison Moderne catalog), Paris, Éditions de La Maison Moderne, 1901, p. 12.

Aquamarine vase from the Cristallerie de Pantin, close to the vase of 2014 from the sélection of vases sold by La Maison moderne. Photo internet, all rights reserved

For the reasons mentioned above, it is unlikely that any of Guimard’s designs were included in this selection. However, the selection only featured designs with abstract, swirling patterns, far from the naturalistic designs copying the Nancy style that the crystal factory produced in abundance using the same type of slightly bluish glass.

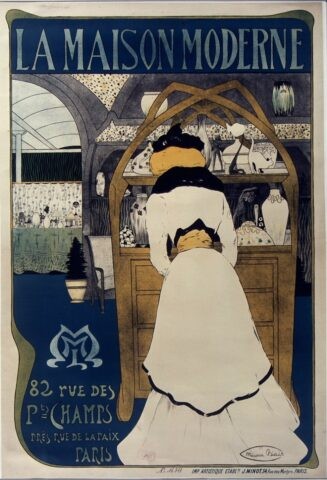

But in the same catalog, the chapter on glassware was written by a friend of Guimard’s, the journalist Georges Bans. In 1895, Bans founded and edited a small bi-monthly literary and artistic magazine, La Critique. Although its circulation was limited, the magazine received contributions from many prominent authors such as Camille Mauclair, as well as excellent illustrators such as Gustave Jossot and Maurice Biais. The latter collaborated with La Maison Moderne, not only with the poster we have already reproduced, but also with drawings of furniture, including an armchair with particularly sober and modern lines.

Maurice Biais, imprimerie J. Minot, poster for La Maison Moderne, 1899-1900, color lithography on paper , ighut. 114 m, width. 0,785 m, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Armchair designed Maurice Biais, Musée d’Orsay, mahogany, leather and brasss, hight. 0,86 m, width. 0,70 m, depth. 0,95 m. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay) / Mathieu Rabeau, rights reserved. This armchair is presented in L’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (La Maison Moderne catalog), « Ameublement et décoration », fauteuil renversé n° 35, p. 16, 1901.

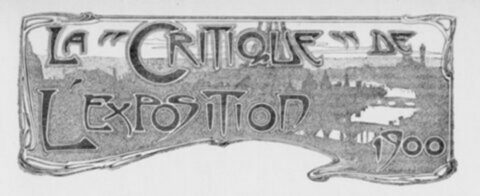

Also noteworthy is the beautiful frontispiece designed for the chronicle of the 1900 World’s Fair in La Critique by Maurice Dufrène, one of the main contributors to La Maison Moderne.

Frontispiece drawn by Maurice Dufrène for the chronicle of 1900 Exposition Universelle in La Critique. Source Gallica.

La Critique was mainly run by Émile Strauss and the poet and critic Alcanter de Brahm (pen name of Marcel Bernhardt). Hector Guimard quickly developed an intellectual rapport and undoubtedly a friendship with the latter, which led to him being frequently quoted in the magazine[3]. Georges Bans also followed Guimard’s career and presented several of his works in La Critique, notably the Paris metro entrances. In a brief note [4] published in August 1900 in La Critique, clearly informed by a disgruntled Guimard, he vigorously contested the battle waged by two city councilors, Charles Fortin and Maurice Quentin-Beauchard, who were fighting to have the kiosks replaced by open surrounds. To restore them, he was appealing to the Prefect of the Seine, Justin de Selves, who was careful not to intervene. A second article by Georges Bans, published two months later in October 1900, this time in L’Art Décoratif, commented very favorably on the installation of the first metro entrances, inventing the famous phrase “the dragonfly spreading its light wings” to describe the inverted roof of the B kiosks. On this occasion, we can guess that Guimard personally explained to him certain details and motivations behind his work that most critics of the time did not perceive.

We can also cite an article by Georges Bans in the German magazine L’Architecture du XXe siècle, which features two drawings of Guimard’s facade elevations and refers to the dinner at La Critique on December 31, 1900, which Guimard attended, as well as the joint participation of Guimard and Bans in the office of the company Le Nouveau Paris, founded in 1903 by Frantz Jourdain.

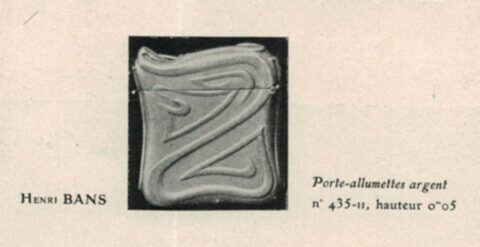

The catalog of La Maison Moderne also features a silver matchbox holder by the young architect Henry Bans[5], brother of Georges Bans.

Henry Bans, matchbox holder, « L’Orfèvrerie », L’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (La Maison Moderne catalog), Paris, Éditions de La Maison Moderne, 1901, p. 11. Coll. part.

Henry Bans was a close friend of the family of sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1829-1875)[6]. Guimard expanded the Carpeaux studio in 1894-1895 on Boulevard Exelmans with the creation of an exhibition gallery dedicated to the sculptor’s work. It was probably on this occasion that he met the Bans brothers.

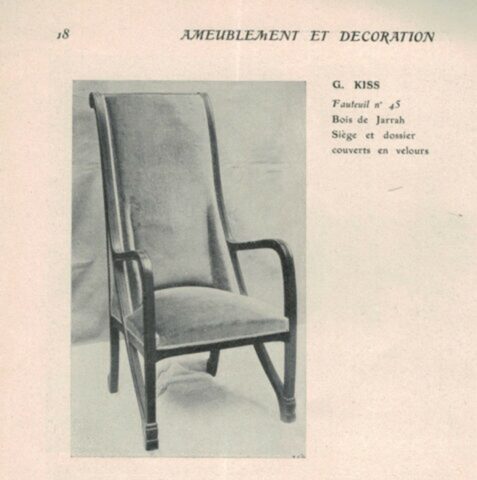

Finally, it is worth noting the presence in the La Maison Moderne catalog of an armchair by Géza Kiss, No. 45 in Jarah wood, which can be seen partially reproduced in Maurice Biais’ poster (see above).

Géza Kiss, armchair n° 45, jarrah wood, seat and back covered in velvet, « Ameublement et décoration », L’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (La Maison Moderne catalog), Paris, Éditions de La Maison Moderne, p. 18, 1901. Private collection

Without going any further (see note 3), we can assure that Kiss, Guimard, the editors of La Critique, and of course Julius Meier Graefe knew each other.

Frédéric Descouturelle

Notes

[1] One immediately thinks that the shop or shops planned for the ground floor of the Castel Béranger, which we do not yet know whether they actually operated, would have been an ideal showcase for Guimard. However, there is no evidence to suggest that he had this intention at any point.[2] Guimard v. Mutel case, ruling of the Seine Commercial Court of January 4, 1901, overturned by the Seine Court of Appeal on January 14, 1904, “Jurisprudence” La Construction Lyonnaise, January 1912.

[3] We will soon review these quotes from Guimard in La Critique.

[4] G. B. “Notule, Le monde à l’envers,” La Critique, August 5, 1900.

[5] François Gabriel Bans, known as Henry or Henri Bans (1877-1970).

[6] Henry Bans would much later design the stele for the Carpeaux monument in Square Carpeaux in Paris’s 18th arrondissement. The monument is adorned with a bust sculpted by Léon Fagel in 1929.

Translation: Alan Bryden