The « Maison Moderne » of Julius Meier-Graefe — Part 2

7 July 2025

Organization, offerings, and operation of La Maison Moderne

Among all the artists selected, two Belgian compatriots were given the most important assignment: Georges Lemmen, first and foremost. Meier-Graefe entrusted him with the task of designing the most recognizable element of the brand: its logo. This symbol, intended to be the “brand” of La Maison Moderne, consisted simply of the initial letters of the gallery’s name superimposed on each other, drawn in curves in line with the style already used by Lemmen in the posters for Dekorative Kunst. Simple in design, this logo appeared on most of La Maison Moderne’s production and publications, in its original or a more elaborate form.

Georges Lemmen, logo of La Maison Moderne, 1899.

The design of La Maison Moderne was commissioned to the artist Meier-Graefe trusted most: Henry Van de Velde. He designed a storefront with display windows, allowing passersby to see a selection of the items sold inside.

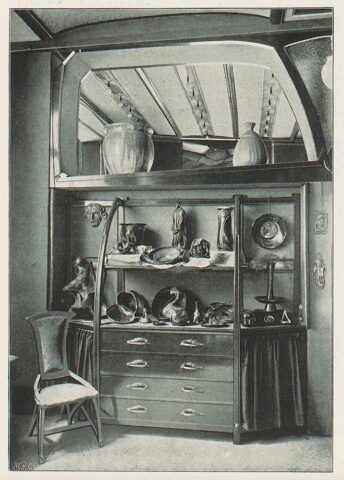

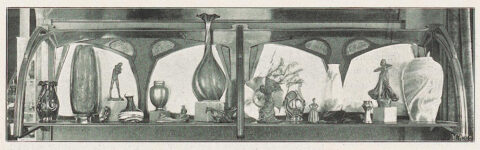

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg. On the shelf of the display cabinet are two vases by Dufrène and Dalpayrat.

Maurice Dufrène, designer, Dalpayrat and Lesbros, ceramist, flamed stoneware, c. 1899, purchased by the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs at La Maison Moderne in 1899, silver mount by Cardeilhac added in 1900, exhibited at the UCAD pavilion at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1900, Musée des Arts Décoratifs. All rights reserved.

The typography for the letters was designed by Georges Lemmen[2]. This choice reflects Meier-Graefe’s confidence in the talent of the two Belgian artists, as the shop front played as important a role as a poster for shops at the end of the 19th century. In the gallery, Van de Velde proposed a complete decor, alternating display cases, shelves, and furnished rooms.

The other artists selected to appear in the gallery catalog were countless: more than sixty were listed. Despite Meier-Graefe’s stated desire to create a gallery that favored French works, foreign artists were very numerous within its walls.

Bernhard Hoetger (Hörde, Germany, 1874 – Beatenberg, Switzerland, 1949), The Storm, c. 1901, bronze, Musée d’Orsay, RF 4189, height 0.311 m, width 0.245 m, depth 0.25 m. All rights reserved. This sculpture is reproduced in Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, bronze 3322-1, La Sculpture p. 5.

To provide an overview of the diversity of the offerings, it is worth mentioning all the nationalities represented among La Maison Moderne’s collaborators: French, Belgian, German, Italian, Austrian, Hungarian, Romanian, Serbian, Danish, Dutch, and Finnish. It is interesting to note the absence of British and Spanish artists among them. Meier-Graefe’s taste is the only real common denominator among all these artists, and they were selected with a concern for consistency that was dear to him (Bing had been criticized for a lack of consistency four years earlier).

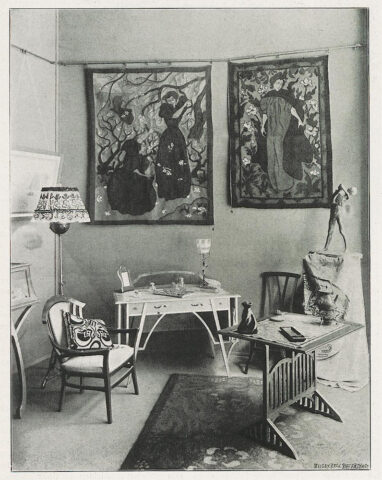

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

The establishment also offered a wide range of products: the article announcing its opening in September 1899 stated that “The galleries of the ‘Maison Moderne’ will contain a little bit of everything: furniture, upholstery fabrics, carpets, ceramics, glassware, lighting fixtures, embroidery, lace, jewelry, fans, toiletries, and fancy items—from brushes to cane knobs—in short, everything for the home and the person[3].” This prediction was clearly confirmed: La Maison Moderne offered everything needed to furnish an interior and all the accessories—except clothing—that a wealthy person in the early 20th century might need. The same article also mentions a selection of master painters whose works were offered for sale: Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Auguste Renoir, Maurice Denis, Théo Van Rysselberghe, Édouard Vuillard, and Pierre Bonnard. However, this article remains the only mention of the painting exhibition at La Maison Moderne. We do not know which paintings were exhibited there, and no other artists can be identified.

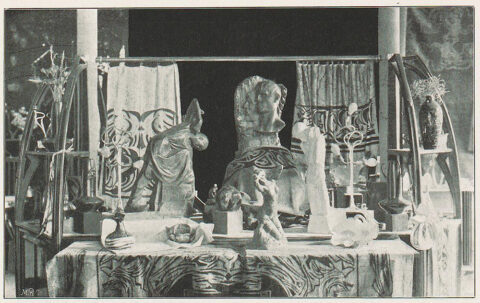

In addition to offering individual items for sale, the gallery also designed and furnished rooms, apartments, and other types of interiors. Most of these complete designs were carried out under the direction of Abel Landry, Pierre Selmershein, or Maurice Dufrène. No examples have survived other than old photographs, such as those of this fashion store, also designed by Van de Velde for the Palast Hotel on Potsdamer Platz in Berlin, managed by P. H. C. Kons.

Henri Van de Velde, interior design of a fashion store “filiale de Madame Henriette” in the Palast Hotel in Berlin, realized by La Maison Moderne with furniture designed by Abel Landry, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

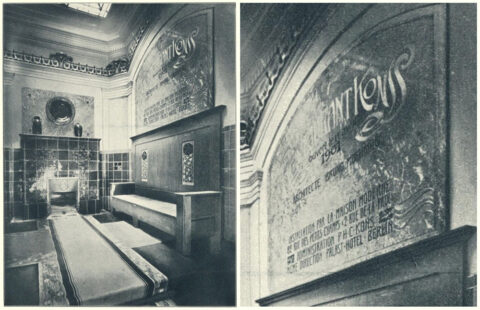

The most important and best documented order was for the interior design of the German restaurant Konss[4], located in Paris on the corner of Rue Grammont and Boulevard des Italiens, on the first floor, also for P. H. C. Kons. The architect appointed by the owner to oversee the work was Bruno Möhring[5]. He decided on the overall layout of the place, and Kons renewed his trust in La Maison Moderne for the design and installation of the decorations. The work took place from January 15 to April 17, 1901. A real success, La Maison Moderne’s participation in the design was noted in the entrance hall of its establishment. A few months later, Meier-Graefe reported on it in L’Art Décoratif, under one of his pseudonyms: G. M. Jacques[6]. Reading this article, it is striking that, having signed it with a French-sounding pseudonym in his French magazine, Meier-Graefe adopts a point of view that could be that of a Parisian journalist, criticizing Möhring’s design by claiming that his “Latin instincts are closed to his Germanic conception.” “when it was in fact his own company that carried out the development. By sticking to what he imagined to be a ”Latin” mindset, he no doubt wanted to avoid any suspicion of a conflict of interest.

Bruno Möhring, landing on the staircase of the Konss restaurant, on the first floor of 30 rue de Grammont in Paris, 1901, executed by La Maison Moderne, ceramics by Laüger, Architektonische Monatshefte, VII. Jahrgang 1901, pl. 88, Leipzig/Vienna, Friedrich Wolfrum, 1901, online library of the University of Stuttgart.

Bruno Möhring, green dining room of the Konss restaurant, first floor of 30 rue de Grammont in Paris, 1901, executed by La Maison Moderne, panels by Georges de Feure, Architektonische Monatshefte, VII. Jahrgang 1901, pl. 87, Leipzig/Vienna, Friedrich Wolfrum, 1901, online library of the University of Stuttgart.

Bruno Möhring, lilac dining room of the Konss restaurant, on the first floor of 30 rue de Grammont in Paris, 1901, executed by La Maison Moderne, L’Art Décoratif, November 1901, article by G. M. Jacques (Julius Meier-Graefe). Online library of the University of Heidelberg.

La Maison Moderne’s operating model is very well thought out, reflecting its director’s careful consideration and innovative abilities. Aware of the behavior of French collectors, who treat art objects in the same way as paintings or sculptures, Meier-Graefe proposed an organization inspired by the Vereinigten Werkstätten für Kunst im Handwerk (United Workshops for Art and Craft) in Munich. While French decorative art remained primarily a commissioned art form, in which artists responded only to specific requests by creating unique models that could not be reproduced, Meier-Graefe proposed the opposite system: objects were no longer commissioned by individuals but were mass-produced by artists and craftsmen. However, production remained in the realm of craftsmanship and did not shift to industry. In the absence of administrative archives from the gallery, no precise figures can be given: the number of pieces produced for the same model must have been relatively small, but there were no unique works. Without even mentioning taste or style, it was first and foremost the way of thinking that the director of La Maison Moderne wanted to change.

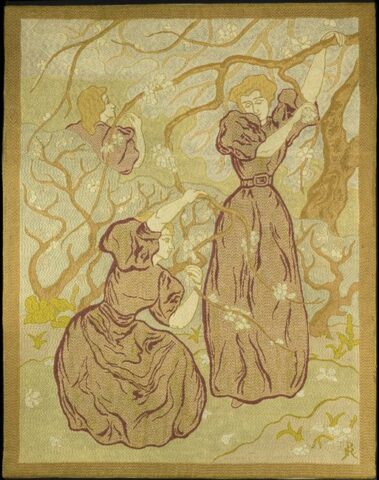

There were exceptions to this system. Tapestries by Paul-Élie Ranson, handmade by his wife France Ranson-Rousseau in single copies, were offered for sale at La Maison Moderne[7].

Paul-Élie Ranson, Printemps (Spring), wool tapestry on canvas executed by France Ranson-Rousseau, 1895, height 1.67 m, width 1.32 m, Musée d’Orsay, OAO 1788, rights reserved.

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris. On the wall, two tapestries by Paul-Élie Ranson: Printemps and Femme en rouge, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

Exhibition Femmes chez les nabis. De fil en aiguille (Women among the Nabis. From thread to needle) at the Pont-Aven Museum (June 22 to November 3, 2024), evoking the room in La Maison Moderne where Ranson’s tapestries were displayed. Photo by Bertrand Mothes.

However, these objects were made before the gallery opened and therefore do not fall under the manufacturing method developed by Meier-Graefe. The principle is simple: artists create designs and grant production rights to the gallery, which is responsible for executing them. The artist receives a portion of the sale price—defined by mutual agreement—for each object sold[8]. The possibility of producing multiple copies also allows Meier-Graefe to sell his objects at a “reasonable price,” in his own words. The “reasonable price” encourages purchases and provides the artist with a comfortable income. Here, “reasonable” should not be confused with “low.” While the prices of the objects sold at La Maison moderne did not reach those seen at Bing, they were nonetheless accessible to fairly well-off individuals, rather than workers or low-paid employees.

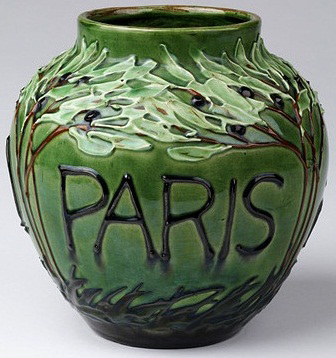

The gallery had its own workshops for the production of objects. The only one that can be confirmed with certainty is the leather workshop[9], but it is possible that there were also workshops for cabinetmaking, tapestry, brasswork, jewelry, and watchmaking. The fire arts, which were difficult to set up on a large scale in the heart of the Parisian capital, came from manufacturers associated with La Maison Moderne. The vase Exposition 1900 Paris, from Germany, is a good example. Manufactured by Tonwerke in Kandern, run by Max Laüger, it is not part of the factory’s usual production but was made exclusively for LMM, as evidenced by the gallery mark incised under its base alongside Laüger’s monogram and the factory mark.

Max Laüger, Tonwerke workshop, Vase Exhibition 1900 Paris, circa 1900, painted earthenware under glaze, produced by La Maison Moderne, height 0.212 m, London, Victoria & Albert Museum. All rights reserved.

Max Laüger, Tonwerke workshop, Vase Exhibition 1900 Paris, circa 1900, painted earthenware under glaze, height 0.212 m, Paris, Musée d’Orsay. All rights reserved.

This approach to production and sales was complemented by a decisive choice of location for the gallery. 82 Rue des Petit-Champs is located just a few meters from Rue de la Paix, which remains one of the most prestigious shopping districts in Paris. In addition to being central, this location was frequented by a wealthy clientele receptive to artistic innovation. The street has since changed its name to Rue Danielle-Casanova. The former number 82 now corresponds to the current number 26, which is now occupied by a café.

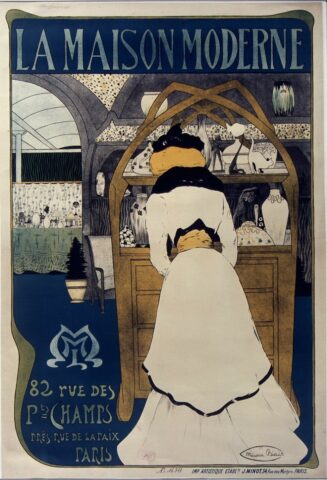

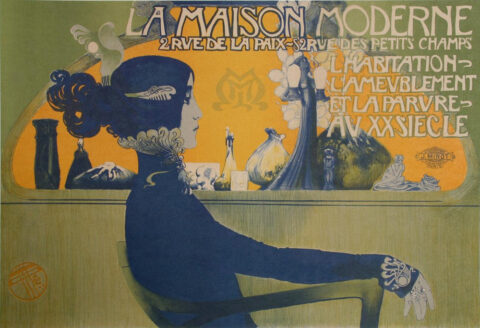

As the director of a commercial establishment, Meier-Graefe naturally used all the means available to him at the time to promote his gallery. Two posters were the cornerstone of his advertising campaign. The first was designed by Maurice Biais. It depicts an elegant lady looking at objects displayed in one of the shop windows designed by Van de Velde, faithfully reproduced.

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

Maurice Biais, J. Minot printing house, poster for La Maison Moderne, 1899–1900, color lithograph on paper, height 114 cm, width 0.785 cm, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The objects depicted on the poster are all the more easily recognizable as Maurice Biais used photographs that would later be incorporated in the La Maison Moderne catalog. Among other items, the poster features a flamed enamel inkwell by Jakob Rapoport designed by Maurice Dufrène, small bronze sculptures by Georges Minne, a porcelain cat from the Danish manufacturer Bing & Grøndahl, and a lamp by Dufrène.

Maurice Dufrène, electric lamp, patinated bronze, no. 1580-1, height 0.55 m, Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (catalogue of La Maison Moderne), 1901, Lighting fixtures, p. 9. Private collection.

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg. To the left of the display case, Le Petit Blessé by Georges Minne.

Georges Minne, Le Petit Blessé, bronze, height 0.25 m, Nationalgalerie, Berlin. All rights reserved. This sculpture is reproduced in Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (catalogue of La Maison Moderne), 1901, La Sculpture, bronze no. 308-1, p. 21.

The second poster is the work of Manuel Orazi (fig. 5). With a composition and atmosphere completely different from that of Biais, it also features objects that were sold there. We can recognize an inkwell bearing a bronze figure by Alexandre Charpentier on a base designed by Dufrène and made of flamed stoneware by Adrien Dalpayrat, an armchair by Van de Velde, a bronze lamp by Gustave Gurschner, a vase by Dufrène and Dalpayrat, and a monkey figurine by Joseph Mendes da Costa. The distinctive feature of this poster is obviously the large, hieratic female figure that adorns it. This is in fact the famous dancer Cléo de Mérode, who lent her image to the gallery as its muse[10].

Manuel Orazi, J. Minot printing house, poster for La Maison Moderne, 1901, color lithograph on paper, height 0.83 m, width 1.175 m, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Gustav Gurschner, electric lamp, bronze, no. 718-1, height 0.48 m including lamps, Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (catalogue of La Maison Moderne), 1901, La Sculpture, p. 13. Private collection.

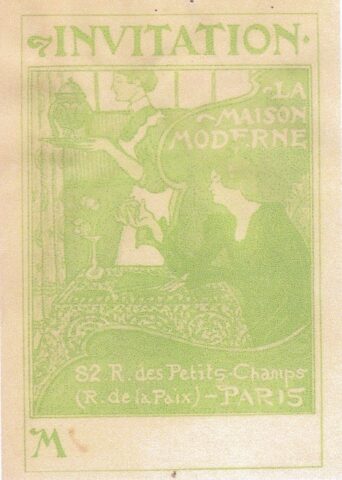

In addition to these posters, Meier-Graefe also published small leaflets designed to promote his gallery. The invitation card for the opening was designed by Georges Lemmen.

Georges Lemmen, invitation card to the inauguration of La Maison Moderne, 1899, color print on paper, height 0.19 m, width 0.13 m. Private collection.

The composition was also used as an advertisement in the pages of L’Art Décoratif. The two women depicted are not anonymous, as they are actually Mrs. Meier-Graefe and Jenny, a young servant.

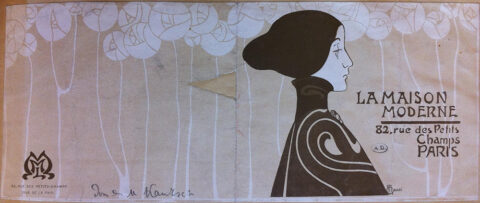

The second print was created by Manuel Orazi, who drew inspiration from his own poster for the design.

Manuel Orazi, brochure for La Maison Moderne, circa 1903, lithograph on paper, height 0.117 m, width 0.277 m, Paris, Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs.

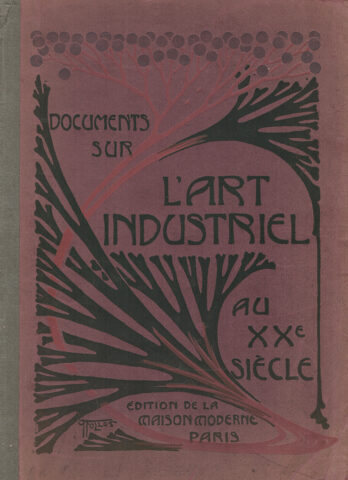

Meier-Graefe also printed discount coupons from the same poster, either for his best customers or to attract new ones. One of his most important advertising tools remained the book Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (Documents on Industrial Art in the Twentieth Century), published in 1901.

Paul Follot, Cover of Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, Paris, Édition de La Maison Moderne, 1901, height 0.30 m, width 0.208 m. Private collection.

Presented as a collection of the most beautiful works of art of the period, it is in fact the gallery’s commercial catalog, containing many references to objects from La Maison Moderne.

Félix Aubert, Maison Georges Robert, Iris fan no. 54-V and its box, c. 1900, polychrome silk lace, horn, emerald, pearl, height 0.28 m, diameter 0.48 m, Caen, Musée de Normandie. All rights reserved. This fan is reproduced in Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, 1901, La Dentelle, p. 4.

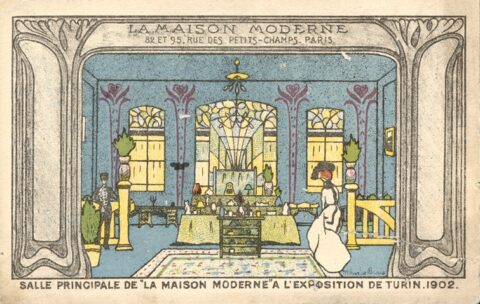

In addition to these independent advertisements, Meier-Graefe filled the magazines he edited with constant references to his gallery and collaborating artists. He also participated in events such as the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts in Turin in 1902, for which he published a postcard featuring real objects from his shop.

Maurice Biais, Société Éditrice Cartoline, Main hall of “La Maison Moderne” at the Turin Exhibition, 1902, vintage postcard, Miami, The Wolfsonian-Florida International University. All rights reserved.

However, despite all its innovative ideas and pioneering role at the beginning of the 20th century, the gallery was a failure. Its director sold it in 1904 to Delrue et Cie, who took charge of liquidating the stock[12]. The climate of xenophobia in Paris was detrimental to both Meier-Graefe and Bing, as French collectors resented a German coming to lecture them on what their taste should be[13]. Furthermore, although its structure was ingenious, production costs remained too high for the gallery to remain viable.

Abel Landry, armchair n° 43, produced by La Maison Moderne, mahogany, modern upholstery, height 1.04 m, width 0.75 m, depth 0.90 m, Zéhil gallery, Monaco. Photo: Zéhil gallery. This armchair is reproduced in Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, 1901, Furniture and decoration, p. 16.

This gallery, led by an innovative director with impeccable taste, never managed to find its audience, but remains the only real attempt in 1900 to create an alliance between art, industry, and commerce.

Bertrand Mothes

Translation: Alan Bryden

Notes

[1] Roger CARDON, Georges Lemmen (1865-1916), Antwerp, Petraco-Pandora, 1990, p. 449.

[2] Cat. Exp Georges Lemmen 1865-1916, Brussels, Crédit Communal, Ghent, Snoeck-Ducaju & Zoon, Antwerp, Pandora, 1997, p. 58.

[3] R. [pseudonym Julius MEIER-GRAEFE], “Chronique de l’art décoratif, La ‘Maison Moderne’,” L’Art Décoratif, September 1899, no. 12, p. 277.

[4] It is likely that the doubling of the final “s” in the restaurant owner’s name was intended to make it sound German and avoid confusion with a French word that was a little too similar.

[5] In 1900, Möhring had already built the Restaurant allemand at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, which was a great success.

[6] G. M. JACQUES, “Un restaurant allemand à Paris,” L’Art décoratif, November 1901, no. 38, pp. 54-60.

[7] Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle. Photographic reproductions of the main works of the contributors to La Maison Moderne. Commented by R. [Raoul] AUBRY, H. [Henri] FRANTZ, G.-M. JACQUES [pseudonym Julius MEIER-GRAEFE], G. [Gustave] KAHN, J. [Julius] MEIER-GRAEFE, Gabriel MOUREY, Y. [Yvanhoé] RAMBOSSON, E. [Émile] SEDEYN, Gustave SOULIER, G. [Georges] BANS, with nine additional illustrations by Félix VALLOTTON Les Métiers d’Art. Paris, Édition de La Maison Moderne, 1901, L’Ameublement, p. 36.

[8] R., op. cit. in note 3, p. 277.

[9] Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, op. cit. in note 7, La Maroquinerie, p. II.

[10] Alexandre Charpentier (1856-1909).Naturalisme et Art Nouveau, exhibition catalog, Paris, Musée d’Orsay, N. Chaudun, 2007, p. 126.

[11] Roger CARDON, Georges Lemmen (1865-1916), Antwerp, Petraco-Pandora, 1990, p. 449.

[12] Advertisement for La Maison Moderne, Delrue et Cie, Fermes et Châteaux, November 1905, no. 3, p. IX.

[13] Nancy J. TROY, Modernism and the Decorative Arts in France: Art Nouveau to Le Corbusier, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1991, p. 47.

List of artists mentioned in the Documents sur l’Art Industriel au XXème siècle (Documents on Industrial Art in the Twentieth Century)

Félix AUBERT

Henri BANS

Gyula BETLEN

Maurice BIAIS

Alexandre BIGOT

[manufacture] BING & GROENDAHLSofie BURGER HARTMANN

Alexandre CHARPENTIER

Cristallerie de Pantin

Jens DAHL-JENSEN

Pierre Adrien DALPAYRAT

Eugène DELATRE

Maurice DUFRÈNE

Paul FOLLOT

Édouard FORTINY

Maurin GAUTHIER

Gustave GURSCHNER

Bernhard HOETGER

Henry JOLLY

Emil KIEMLEN

G. KISS

Abel LANDRY

Georges LEMMEN

Hans Stoltenberg LERCHE

Clément MÈRE

Charles MILÈS

Georges MINNE

Koloman MOSER

Gabriel OLIVIER

Manuel ORAZI

Blanche ORY-ROBIN

Paul-Élie RANSON

Jakab RAPOPORT

Auguste RODIN

SAINT-YVES SCHLESINGER

Elisabeth SCHMIDT-PECHT

Tony SELMERSHEIM

Louis Comfort TIFFANY

Henry VAN DE VELDE

Heinrich VOGLER

Félix VOULOT

François WALDRAFF

To quote this article:

Bertrand MOTHES, “La Maison Moderne de Julius Meier-Graefe” in Catherine Méneux, Emmanuel Pernoud, and Pierre Wat (eds.), Proceedings of the Study Day Actualité de la recherche en XIXesiècle, Master 1, Years 2012 and 2013, Paris, HiCSA website, published online in January 2014.