What color were the red signaling glasses on Guimard’s metro surrounds?

( Note: in this article, the term “signaling glass” is used to translate the French “verrine”, meaning the protective cover of the lamp in a Guimard Metro candelabra)

Due to the flow of contradictory information, we are being urged from all sides to give our opinion on this crucial point. We are happy to oblige, all the more so as we had neglected to add any nuances to the overly clear-cut opinion, we expressed in the two books published in 2003 and 2012 that established a serious study of Guimard’s metro [1]. The recent discovery of a color photograph taken in the 1960s is a fitting conclusion to our article.

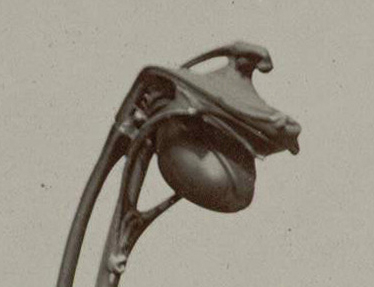

To define the curved glass pieces that complete the candelabras on the open surrounds of Guimard’s Paris metro entrances, we have adopted the term used at the time by the CMP (Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris), “signaling glass”, rather than “globe”, which refers to an image of a sphere [2]. Due to the low luminosity of their electric bulb, which is entirely covered by the signaling glass, the function of these lights is nocturnal signaling rather than lighting. This latter function, which Guimard had not foreseen, as it had not been requested [3], was gradually taken over by uncovered lamps installed by CMP on the aediculae and on certain open surrounds. The surrounds of the additional entrances [4], which at the time were used solely for exiting, had neither luminous signage nor lighting.

Originally, these signaling glasses were indeed made of glass. For a more complete study, we refer the reader to our dossier Hector Guimard, Le Verre pp. 20-23, published in pdf format in 2009 and still accessible on our website. We give some extracts below.

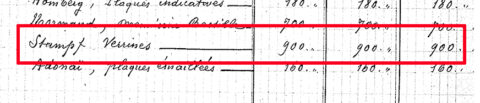

We know the supplier of these signaling glasses thanks to a few rare archives. The first is a CMP accounting document, dated September 12, 1901, listing the names of the various suppliers and the costs incurred with each of them for Guimard’s first project, i.e. the construction of surface accesses for line 1 and two additional sections of future lines 2 and 6. Entitled “Travaux des édicules/M. Guimard Architecte”, this document actually lists the costs incurred for both the aediculae and the uncovered surrounds. The penultimate line of the document reads: “Stumpf, Signaling glass […] 900”.

Detail of a breakdown of surface access expenses for the first Paris metro project. RATP document.

This company, better known as “Cristallerie de Pantin”, had been called Stumpf, Touvier, Viollet et Cie since 1888. It was founded in La Villette in 1851 by E. S. Monot, then transferred to Pantin in 1855. It rapidly prospered, becoming France’s third-largest crystal works (after Baccarat and Clichy) after the 1870 war (and the transfer of the Saint-Louis crystal works to German territory). In 1919, it was absorbed by the Legras glassworks (Saint-Denis and Pantin Quatre-Chemins).

The price of 900 F-gold corresponds to 30 signaling glass at 30 F-gold each, i.e. 13 pairs of signaling glass for the 13 uncovered surrounds of the first project, plus 4 additional pieces in case of breakage. This price per unit is confirmed by another undated CMP accounting document for line 2, which sets the price of two signaling glass for each frame on the section from Villiers to Ménilmontant stations at 60 gold Francs. It was clearly stated that this price was identical to that set for the surrounds on the first site. The Cristallerie de Pantin’s commitment to Guimard and the CMP to maintain the price of glassware for Line 2 surrounds is also the subject of three documents (one handwritten and two typewritten) from November 1901 to January 1903.

There were 103 Guimard surrounds on the network, and twice as many signaling glass on their lampposts. They were still in place in 1960, when Louis Malle filmed ” Zazie dans le métro”, based on the novel by Raymond Queneau.

Catherine Demongeot for Zazie dans le Métro in 1960, promotional photo or set photo for a scene not included in the film. The signaling glass shows the characteristic glass stopper at the tip. Private collection.

Early loans (later transformed into donations) of Guimard surrounds, complete or otherwise, enabled the preservation of their glass cases. Thus, the portico of the uncovered surround at Raspail station, installed in 1906, entered the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1958. The same is true of the surround for Bolivar station, installed in 1911, which entered the collections of the Staatliches Museum für Angewandte Kunst in Munich in 1960 (not on display).

Portico from the uncovered surround of the Raspail station at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The portico includes red glass signaling glass. All rights reserved.

In 1961, the Musée National d’Art Moderne de Paris also received a complete surround, one of two from the Montparnasse station (installed in 1910). Returned to the Musée d’Orsay, it can be viewed on the occasion of thematic exhibitions.

Portico of an open surround from the Musée d’Orsay, loaned (then donated) by the RATP in 1961 to the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris, from the Montparnasse station (1910), with the exception of the enameled lava sign (before 1903). The signaling glasses are indeed glass. Photo D. Magdelaine.

Shortly afterwards, in 1966, the RATP donated a complete Guimard surround (without sign holder) to the Montreal metro company. The seven-module long, five-module wide entourage was composed from elements taken from the reserves and resulting from the dismantling of certain entrances. It included two glass signaling glass

The Guimard open surround for Montreal’s Victoria metro station, in storage prior to shipment in 1966. Photo RATP.

So it was only later, at a date that is still difficult to pin down, that RATP replaced the glass signaling glass with red synthetic equivalents, which were cheaper, less fragile, but far less beautiful. However, as a symptom of RATP’s long lack of interest in this period of its history, the signaling glass that had been salvaged from these exchanges mysteriously disappeared from its reserves, so that by the end of the twentieth century it no longer possessed a single one.

As luck would have it, during restoration work on the entrance to Montreal’s Victoria station, the STP metro company had the wisdom to replace its somewhat damaged glass signaling glass and give one back to the RATP in 2003 [5]. This was the first signaling glass we had the opportunity to examine up close, admiring its clean lines, satin-finish surface and color, which varies from dark red to light orange, depending on the lighting and the thickness of the glass.

Glass signaling glass of an uncovered Guimard surround, from the uncovered surround offered to Montreal in 1966 and donated to the RATP in 2003. Photo F. D.

We have also learned of the existence of a signaling glass [6], also red, on a copy of a Guimard bronze surround in the USA. This unexpected presence, attested to by a State report [7] drawn up in 2002, confirms the existence of a network for the fraudulent export of Guimard metro parts to the USA.

Copy of a bronze surround placed around a pond in Houston in the 2000s. Photo Artcurial.

For the supply of special glass for the windows and roofs of kiosks and pavilions, we have a contract between CMP (Compagnie du Métro Parisien) , Compagnie de Saint-Gobain and glassmaker Charles Champigneulle. This contract clearly specifies the color of the glass prescribed. However, we have no record of an initial contract for the supply of the signaling glass, which would undoubtedly have enabled us to know the color originally envisaged by Guimard. Given the color of the known glass signaling glass, all orange-red, we logically assumed that they all were. This opinion was supported by the fact that on some old black-and-white shots, considering the reflection of light, the signaling glass appears to be dark, which is compatible with a red color.

Uncovered surround of the Rome station, installed in 1902. Photo Charles Maindron (1861-1940) CMP photographer. Silver chloride gelatin print developed on June 5, 1903. École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, Direction de la documentation, des archives et du patrimoine.

However, this opinion has been challenged by several facts.

The first, to which we should have paid more attention, is the autochrome photograph (giving the actual colors) of Porte d’Auteuil station, dated May 1, 1920 and held in the collection of the Musée Départemental Albert-Kahn. We were unable to reproduce this photograph in the book Guimard, L’Art nouveau du métro due to the museum’s opposition to its publication. Since then, having been included in an exhibition, it has been re-photographed by visitors and is now accessible to all thanks to Wikipedia.

.

Surround of the Porte d’Auteuil station. Photo Heinrich Stürzl, based on an autochrome plate by Frédéric Gadmer, taken May 1, 1920. Musée départemental Albert-Kahn collection (inv. A 21 126). Source Wikimedia Commons.

This picture clearly shows that the signaling glasses are white, not red. To the best of our knowledge, we have no other autochrome images of the period. In our opinion, colorized postcards such as those in the “Le Style Guimard” series, published in 1903 on Hector Guimard’s initiative, cannot serve as a reliable reference, since the process consists in softening the contrast of a black-and-white shot and superimposing transparent flat tints of color which, while often plausible, are sometimes different from reality.

Antique postcard “Le Style Guimard” published in 1903. Private collection.

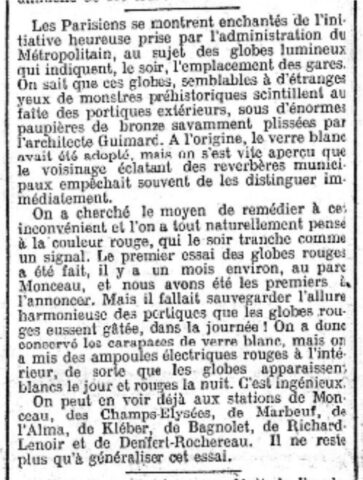

Secondly, the existence of an article published in 1907 in the conservative daily Le Gaulois definitively calls into question the certainty of the exclusive red color of the signaling glasses. We missed this newspaper article in 2003 and 2012. We owe its discovery to an author we will not name.

Unnamed author : echoes from everywhere Le Gaulois September 18, 1907.

This article begins by explaining why red was preferred to white: more effective night-time signage. It also seems to settle the question of the change of color by establishing that in August 1907, CMP carried out a trial of red signaling glasses on the open surround of Monceau station (line 2), and that a month later, in September 1907, seven more stations were fitted with them. At the same time, on other Guimard surrounds, the CMP had obtained a red color by placing red bulbs in the white glasses. It should be noted in passing that the author justifies this temporary measure by “[safeguarding] the harmonious allure of the porticos, which the red globes would have spoiled during the day”. This justification is all the more strange given that red, acting as a complementary color to the green of the fonts, is more pleasing to the eye than white. Did the journalist copy a “piece of language” communicated by the CMP?

By 1907, red signaling glasses were destined to gradually replace white ones. And yet, it is highly likely that the surrounds of Rome station, photographed with certainty in 1903, already featured red glasses, as can be seen in this enlargement of Charles Maindron’s photograph (see above).

Open surround of the Rome station (detail), installed in 1902. Photo Charles Maindron (1861-1940) CMP photographer. Silver chloride gelatin print developed on June 5, 1903. École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, Direction de la documentation, des archives et du patrimoine.

On the contrary, the autochrome plate of the Porte d’Auteuil surround (see above) shows white signaling glasses. In this case, however, it was one of the very last Guimard surrounds to be installed by the CMP, on line 10 in 1913 [8]. Logically, therefore, it should have been fitted with red glasses. But at a time when there was no doubt talk of definitively abandoning the use of Guimard entrances, it is likely that white signaling glasses from earlier replacements were used.

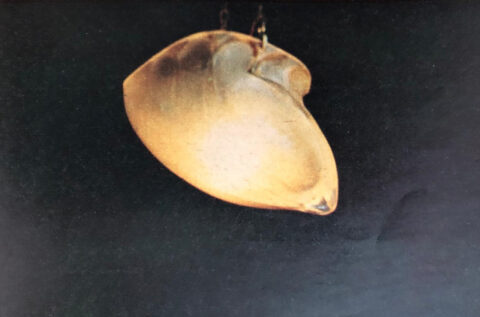

To conclude this little study, we finally had the opportunity to discover the image of a white signaling glass thanks to the photographic collection bequeathed to The Cercle Guimard by our friend Laurent Sully Jaulmes. It is just a detail from a very surprising shot taken in Germany in 1967, which we’ll come back to one day. On this occasion, the signaling glass was used as a chandelier.

White signaling glass used as a chandelier. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulmes (detail), 1967. Cercle Guimard archives and documentation center.

So we don’t despair of seeing signaling glass arrive on the art market in the next few years, because we can’t believe that almost all of those that were originally set up have subsequently been destroyed. On the contrary, a sufficient number of them must still be in private storage. As new generations arrive, they will inevitably reappear, allowing us to take a closer look at these magnificent glass vessels, whether red or white.

Frédéric Descouturelle

Translation: Alan Bryden

Notes

[1] Descouturelle Frédéric, Mignard André, Rodriguez Michel, Le Métropolitain de Guimard, éditions Somogy, 2003; Descouturelle Frédéric, Mignard André, Rodriguez Michel, Guimard, L’Art nouveau du métro, éditions de La Vie du Rail, 2012. [2] One of the earliest designs for a surround with a rounded base, project no. 2, was not validated by the authorities, and featured globular-shaped signaling glasses clamped in a cast-iron jaw, see our article Un porte-enseigne défaillant sur les entourages découverts du métro. [3] The 1899 competition (in which Guimard did not take part) stipulated the presence of a signpost for open surrounds, without mentioning a light source. However, most candidates included one in their proposals. [4] Low cartouche surrounds installed on the network from 1903-1904. [5] The other signaling glass was entrusted to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. [6] One of the signaling glasses was then stored and replaced by an equivalent in synthetic material. [7] This condition report, carried out at the home of the owner of the surround copy in Houston, was written on June 27, 2002 and signed by Steven L. Pine, decorative arts conservator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and a specialist in metal conservation. It refers to a previous report of June l6, 1999. [8] It also shared with the Chardon-Lagache station a peculiarity in the way the crests were hung, a sign, perhaps, of a change in the assembly teams.